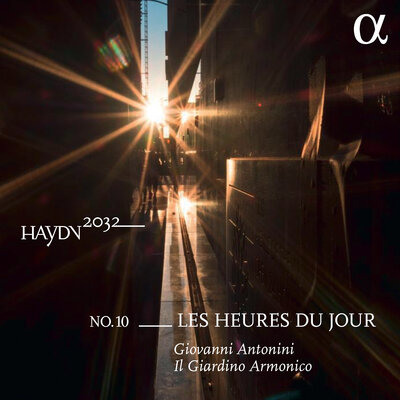

NO.10 __LES HEURES DU JOUR

Il Giardino Armonico

Giovanni Antonini, conductor

Margriet de Moor, writer

Jérôme Sessini, photographer

Symphonies No.6 "Le Matin", No.7 "Le Midi" and N.o8 "Le Soir"

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791): Serenade D Major "Serenata notturna"

Program

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732–1809): Symphony No.6 D Major «Le Matin» Hob. I:6 (Eisenstadt / Vienna 1761)

Adagio – Allegro / Adagio – Andante – Adagio / Menuet – Trio / Finale. Allegro

SYMPHONY NO.6 D MAJOR «LE MATIN» HOB. I:6 (Eisenstadt / Vienna 1761)

Time of creation: till 1733 [1761]

Adagio – Allegro / Adagio – Andante – Adagio / Menuet – Trio / Finale. Allegro

by Christian Moritz-Bauer

The contract of employment ‘concluded for at least three years’, which the newly appointed ‘Vice – Capel – Meister’ Joseph Haydn signed on 1 May 1761 in the apartments of the Palais Esterházy on the Wallnerstraßein Vienna, bound him to a total of fourteen more or less strictly formulated clauses. For a salary of 400 Rhenish florins, he committed himself to take responsibility for the full range of activities of the Esterházy musical establishment in Vienna and the various princely dominions (with the exception of the ‘Chor – Musique’, i.e. the sacred choral music, in Eisenstadt) and to furnish new compositions as required by ‘His Serene Highness’. Furthermore, he should ‘appear daily . . . in the antechamber before and after midday, and inquire whether a high princely order for a musical performance has been given’.

A situation such as this seems to be recalled in the ‘Fifth Visit’ (interview), dated 11 May 1805, of Albert Christoph Dies’s Biographische Nachrichten von Joseph Haydn, which reports how his Prince once gave Haydn ‘the four times of day [Tageszeiten] as the subject of a composition’. Even if the resulting pieces were not four in number and were certainly not ‘in the form of quartets’ (as Dies states), they are without doubt among Haydn’s most frequently performed early works: the symphonies Le Matin, Le Midi and Le Soir.

While Le Midi has survived in an autograph dated 1761 that was preserved like a treasure in the composer’s personal collection throughout his life, only copies of its two sister works have come down to us, although their pertinent titles, mostly indicated in French, and their compositional characteristics leave no doubt that they belong to the same cycle.

Over the years, commentators have attempted to attach many a compositional template to Haydn’s Tageszeiten Symphonies. From the point of view of subject matter, there is, for example, theNeuer und sehr curios-Musicalischer Calender, Parthien-weiß mit 2 Violinen und Basso ò Cembalo in die zwölf Jahrs-Monat eingetheilet (New and very curious musical calendar in the style of suites, with two violins and basso or harpsichord, and divided into the twelve months of the year) written by Gregor Joseph Werner, Haydn’s superior at the time of the trilogy’s composition. Or a series of four ballets – entitled Le Matin, Le Midi, Le Soirand La Nuit – which sought to depict ‘rustic occupations and amusements over the four times of day’. These have been attributed to the composer Joseph Starzer and were performed in Laxenburg in 1755, with choreography by Franz Anton Hilverding. However, the corporation of music writers has declared the absolute favourite among possible models for Haydn’s triptych to be Antonio Vivaldi’s set of four violin concertos Le quattro stagioni, part of his op.8 collection Il cimento dell’armonia e dell’inventione (The contest between harmony and invention), which he dedicated to Count Wenzel von Morzin. (The latter, incidentally, was an uncle twice removed of Haydn’s first employer, Carl Joseph Franz von Morzin, and Vivaldi’s set of concertos also figures in the thematic catalogue of the Esterházy musical collections compiled under Prince Paul Anton around 1740.)

An additional area of discussion concerns the possible direct or indirect reasons why the works were composed, the commission that produced them, and precisely when and where they were given their first performance. Here are a few relatively reliable answers to these questions, which earlier Haydn scholars have been able to unearth from the obscurity of the past.

The Tageszeiten Symphonies may indeed have been written close to the time when the contract with Haydn was concluded and other musicians were engaged for the Esterházy court orchestra, among them the flautist and oboist Franz Sigl (contract of 7 May 1761) – according to Sonja Gerlach’s research, however, they came only after Symphonies nos.15 and 3,1 both of which have already been performed in the Haydn2032 series. A clue as to the date of composition is provided by the diary of Count Carl von Zinzendorf. On the evening of 22 May 1761 he attended a musical evening at the Palais Esterházy, where he heard a currently popular song, ‘Je n’aimais pas le tabac beaucoup’, which is quoted in the opening movement of Le Soir. (The air was written by no less a personage than Christoph Willibald Gluck for an opéra-comique called Le Diable à quatre, produced by the Théâtre Français of Vienna in 1759. It was a box-office hit and was revived on 11 April 1761, only a few weeks before the soirée in question.) Another factor that has been adduced is an astronomical event that caused much discussion in enlightened circles at the time and brought the capital of the Habsburg Empire an illustrious guest in the person of the French astronomer and cartographer César François Cassini de Thury, who seemed to be omnipresent in the Viennese aristocratic salons of the day: the transit of Venus that took place on 6 June 1761. The simultaneous observation and measurement of this phenomenon from various locations all over the globe was to provide scientists with information about the distance of the Earth from the Sun and ultimately – although only in later centuries – led to the exact determination of what we now call the astronomical unit. Since Esterházy family history was also characterised by a well-nigh hereditary interest in studying the heavens, this celestial spectacle may well have played a role in the choice of theme, especially as it was Paul Anton, once a student at the University of Leiden,2 who commissioned the composition of the Tageszeiten. And, according to Elaine Sisman, the trilogy evokes not only the motif of simple rural life dependent on the rhythm of nature, a widespread literary and pictural topos at the time, but also the diurnal course of the sun’s orbit, or the respective position of the heavenly body that grants us light and warmth in the morning, at noon and in the evening: ‘Haydn’s sun’, with which the music begins in eminently programmatic vein, ‘casts light on the worlds of science and religion and nature and art.’3

Of the three sunrises featured in Haydn’s compositional œuvre, the one in Le Matin is by far the earliest example. Like the comparable moments in Die Schöpfung (The Creation, premiered on 30 April 1798; instrumental prelude to Uriel’s recitative ‘In vollem Glanze steiget jetzt die Sonne strahlend auf’) and Die Jahreszeiten (The Seasons, premiered on 24 April 1801; ‘Sie steigt herauf, die Sonne’, chorus with soloists from ‘Der Sommer’), it is in D major (here, as in Die Schöpfung, it even begins on a single, unaccompanied D), works its way up the scale and cadences on the dominant at the dynamic climax.

The fact that Paul II Anton was not only a passionate lover of music – in both of the leading national styles of the time, Italian and French – but also a flautist of considerable talent was an open secret to his social circle. This also explains the quite untypical beginning of the Allegro that follows the sunrise in Haydn’s early symphonic work: the flute reveille (soon imitated by the oboes) is heard piano, and nature begins to stir in alternating forte and piano sections. When finally, instead of the expected entrance of the recapitulation, the horns rush in two bars ahead of the flute theme with a resounding unison, this is certainly to be understood as an allusion to another great passion which seems to be ‘running through the Prince’s mind’ here: the hunt, of course . . .

Hermann Kretzschmar averred that the brief Adagio which frames the ensuing Andante was intended to be a parody of a morning solmisation lesson, followed by humorous demonstrations of the schoolmaster’s virtuosity.4 Elaine Sisman strongly disagrees, seeing in this music the ‘rising of other heavenly bodies’ accompanying the Sun in the morning, such as the Moon or – as we have already mentioned – Venus: ‘Morning entails a banishment of night, a turn from Diana to Aurora, revealing the increasing irrelevance of the Moon – itself still usually present in the sky at dawn.’5 In this sense, Sisman suggests, the image of the singing teacher should probably be rectified; we should imagine Helios (or his successor Phoebus Apollo) with the sun-chariot accompanied by the Horae,6 a mythological theme that the Esterházy princes repeatedly placed on the ceiling frescoes of their magnificent palaces with a view to iconographical self-aggrandisement.

After the clouds trailing the Moon have been dispersed, a minuet is heard, in which the Sun excels as dancing master. The soloists on the dance floor once again include the flute, along with the oboes, the bassoon and finally, in the Trio, the viola and, for the first time in this cycle, the five-stringed violone, also known as the Wiener Quart-Terz-Violon. The concluding Allegro was described by H. C. Robbins Landon, in an apt metaphor, as ‘a brilliantly original way of pouring new wine into old bottles’, by which he meant that the compositional principle of the concerto grosso – the flute, the cello, even the two horns, but above all the violino principale, the part taken by Haydn himself, are awarded solo tasks to perform – appears filled with new life.7

While respectfully noting the objection once raised by Peter Gülke to the manifold attempts to construe the Tageszeiten Symphonies – ‘[Haydn] borrows the semblance of the wholly programmatic and [yet] writes music of such structural autonomy that there is really no need for the clues to concepts provided by the titles’8 – our reflections have now reached Le Midi, the only work of the cycle for which the composer’s manuscript has survived.

The opening movement of this C major symphony, with its slow introduction animated by broad gestures, prominent double-dotting borrowed from the ouverture à la française, and expansive twelve-part scoring, is certainly capable of conjuring up the idea of a sumptuous midday meal accompanied by table music. This is ‘confirmed’ to a certain extent in the ensuing Allegro by the concertante solo entrances of two solo violins, a solo cello, the two oboes and the bassoon, framed by rushing semiquaver figuration. But, all of a sudden, the festive mood changes. If the following pair of movements, consisting of a sombre instrumental recitative and a ‘liberating’ transition into a ‘richly figured dialogue between a solo violin and a solo cello’9 complete with fully written-out cadenza, is indeed to be understood as a parody of a ‘postprandial’ midday concert,10 then the audience would probably have had to be given a powerful aid to digestion. At any rate, Lukas Haselböck11 and, once again, Elaine Sisman have an alternative reading to offer: this alludes to the first movement of the ‘Summer’ concerto (L’estate) from Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, to which the recitative movement of Haydn’s symphony bears an ‘uncanny resemblance’.12 Both writers trace it back to a narrative tradition rooted in ancient poetry, according to which noon represents the hour when, ‘with often catastrophic consequences’, gods become visible to humans and the latter seek refuge when ‘light, heat, . . . silence and stasis become too oppressive’. It is precisely that place of refuge, ‘[t]he shady grove, the valley of purling streams and breezes [that] now appear more vividly, in the succeeding Adagio, with murmuring flutes in thirds’,13 preparing a pastorale-like backdrop for the protagonists, violin and cello. Thus it seems entirely fitting that the following minuet should be more rustic than courtly, while the Finale once again abandons itself to the skilful combination of symphonic and concertante styles, so that the special tonal charm of this Allegro stems from the contrasting juxtaposition of the violini concertati with the flute part, which is again reduced to a single instrument.

As has been noted above, Le Soir takes its theme from the ‘Tobacco Song’ in Gluck’s from Le Diable à quatre(the title of the eponymous opéra-comique means, in French, a turbulent character who makes a lot of noise and causes disorder). This is quoted in extenso and runs right through the opening movement, finally getting canonic treatment. And here we return to the question of what might originally have been the idea behind the commission to compose the Tageszeiten Symphonies. Daniel Heartz, who identified the Gluck quotation, developed the following thesis – starting out from the assumption that Haydn’s employer had fully informed him of his particular predilection in this regard:

Just as the high nobility around Maria Theresia was generally influenced by French culture, so too was Prince Anton Esterházy, who knew Paris and had built up a library of French books, scores and pictures, which was constantly supplied with the latest Parisian publications, for example with Rousseau’s writings (banned in Austria!) in 1761. It is not far-fetched to assume that he was also familiar with the works of François Boucher, which were in great demand at the time. Boucher painted a series of pictures called ‘The hours of the day of a lady of fashion’ [Les Heures du jour d'une femme élégante] for the Swedish ambassador to Paris in 1745. Another series, Points du Jour [Moments in the day], contains a picture called Le Soir with the subtitle ‘La Dame allant au Bal’[The lady going to the ball], accompanied by a quatrain commenting on it.

Did this fashionable lady perhaps even serve as a model for Margot? Margot, who goes out with the intention of dancing and – instead of the verse in the picture – sings her ‘Tobacco Song’. Finally . . . we recall that Haydn concludes his ‘Evening’ Symphony with La Tempesta. The background seems ambiguous: is it a thunderstorm, as invoked by the wicked Marquise, Margot’s antagonist? Is it the sky that masses in a thunderstorm – as an eventful finale at the end of the day?14

The notion of a company sitting together of an evening, enjoying singing, the beauty of the sunset, dance, and the comfort of a dwelling sheltered from the capricious weather that follows a hot summer’s day – all of this may very well have corresponded to the thoughts that ran through Haydn’s mind as he composed Hob. I:8. Perhaps it should be noted here how ingeniously he handles the traditional topoi of storm and tempest music in the Finale of Le Soir. Contrary to expectations, he is distinctly circumspect in his use of them, always anxious to give the soloists of his instrumental ensemble every conceivable freedom to present their virtuoso skills.

1 In Giuseppe Carpani’s biography Le Haydine we even read of another ‘solemn’ symphony already written for Paul Anton’s birthday on 22 April 1761, which Daniel Heartz surmised was the Symphony in C major Hob. I:25.

2 What is thought to have been the world’s first university observatory opened in Leiden (Netherlands) in 1633.

3 Elaine Sisman, ‘Haydn’s Solar Poetics: The Tageszeiten Symphonies and Enlightenment Knowledge’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, vol.66, no.1 (Spring 2013), pp.5-102, here p.91.

4 Hermann Kretzschmar, ‘Die Jugendsinfonien Joseph Haydns’, Jahrbuch der Musikbibliothek Peters, vol.15, 1908, pp.69-90, here p.84.

5 Sisman, p.55.

6 The Horai in Greek mythology, goddesses of the seasons and the natural divisions of time; their name is often translated as ‘the Hours’. (Translator’s note)

7 H. C. Robbins Landon, Haydn: Chronicle and Works, vol. 1, Haydn: The Early Years, 1732-1765 (London: Thames and Hudson, 1980), p.556.

8 Peter Gülke, ‘Haydns “Tageszeiten”-Sinfonien’, in id., Die Sprache der Musik. Essays zur Musik von Bach bis Holliger (Stuttgart, Weimar, Kassel: Bärenreiter/Metzler, 2001), pp.170-175, here p.170f.

9 Walter Lessing, Die Sinfonien von Joseph Haydn, vol. 1 (Baden-Baden: Südwestfunk, 1987), p.36.

10 Jürgen Braun, Sonja Gerlach, Sinfonien 1761 bis 1763. Joseph Haydn-Institut Köln (eds.): Joseph Haydn Werke, Series I, vol.3 (Munich: Henle, 1990), p.VIII.

11 Lukas Haselböck, ‘Vivaldi’s Le quattro stagioni und Haydn’s Tageszeiten-Sinfonien’, in Laurine Quetin, Gerold W. Gruber and Albert Gier (eds.), Joseph Haydn und Europa vom Absolutismus zur Aufklärung (= Musicorum 7; Tours: Université François Rabelais, 2009), pp.183-192.

12 Sisman, p.61.

13 Sisman, p.66.

14 Daniel Heartz, ‘Haydn und Gluck im Burgtheater um 1760: Der neue krumme Teufel, Le Diable à quatre und die Sinfonie “Le soir”’, in Christoph-Hellmut Mahling and Sigrid Wiesmann (eds.), Gesellschaft für Musikforschung. Bericht über den Internationalen Musikwissenschaftlichen Kongreß Bayreuth 1981 (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1984), pp.120-135, here pp.132, 135.

to the shop

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732–1809): Symphony No.7 C Major «Le Midi» Hob. I:7

Adagio – Allegro / Recitativo. Adagio – Allegro – Adagio / [Duetto.] Adagio / [Menuet] – Trio / Finale. Allegro

SYMPHONY NO.7 C MAJOR «LE MIDI» HOB. I:7 (Eisenstadt / Vienna 1761)

Time of creation: 1761

Adagio – Allegro / Recitativo. Adagio – Allegro – Adagio / [Duetto.] Adagio / [Menuet] – Trio / Finale. Allegro

by Christian Moritz-Bauer

The contract of employment ‘concluded for at least three years’, which the newly appointed ‘Vice – Capel – Meister’ Joseph Haydn signed on 1 May 1761 in the apartments of the Palais Esterházy on the Wallnerstraßein Vienna, bound him to a total of fourteen more or less strictly formulated clauses. For a salary of 400 Rhenish florins, he committed himself to take responsibility for the full range of activities of the Esterházy musical establishment in Vienna and the various princely dominions (with the exception of the ‘Chor – Musique’, i.e. the sacred choral music, in Eisenstadt) and to furnish new compositions as required by ‘His Serene Highness’. Furthermore, he should ‘appear daily . . . in the antechamber before and after midday, and inquire whether a high princely order for a musical performance has been given’.

A situation such as this seems to be recalled in the ‘Fifth Visit’ (interview), dated 11 May 1805, of Albert Christoph Dies’s Biographische Nachrichten von Joseph Haydn, which reports how his Prince once gave Haydn ‘the four times of day [Tageszeiten] as the subject of a composition’. Even if the resulting pieces were not four in number and were certainly not ‘in the form of quartets’ (as Dies states), they are without doubt among Haydn’s most frequently performed early works: the symphonies Le Matin, Le Midi and Le Soir.

While Le Midi has survived in an autograph dated 1761 that was preserved like a treasure in the composer’s personal collection throughout his life, only copies of its two sister works have come down to us, although their pertinent titles, mostly indicated in French, and their compositional characteristics leave no doubt that they belong to the same cycle.

Over the years, commentators have attempted to attach many a compositional template to Haydn’s Tageszeiten Symphonies. From the point of view of subject matter, there is, for example, theNeuer und sehr curios-Musicalischer Calender, Parthien-weiß mit 2 Violinen und Basso ò Cembalo in die zwölf Jahrs-Monat eingetheilet (New and very curious musical calendar in the style of suites, with two violins and basso or harpsichord, and divided into the twelve months of the year) written by Gregor Joseph Werner, Haydn’s superior at the time of the trilogy’s composition. Or a series of four ballets – entitled Le Matin, Le Midi, Le Soirand La Nuit – which sought to depict ‘rustic occupations and amusements over the four times of day’. These have been attributed to the composer Joseph Starzer and were performed in Laxenburg in 1755, with choreography by Franz Anton Hilverding. However, the corporation of music writers has declared the absolute favourite among possible models for Haydn’s triptych to be Antonio Vivaldi’s set of four violin concertos Le quattro stagioni, part of his op.8 collection Il cimento dell’armonia e dell’inventione (The contest between harmony and invention), which he dedicated to Count Wenzel von Morzin. (The latter, incidentally, was an uncle twice removed of Haydn’s first employer, Carl Joseph Franz von Morzin, and Vivaldi’s set of concertos also figures in the thematic catalogue of the Esterházy musical collections compiled under Prince Paul Anton around 1740.)

An additional area of discussion concerns the possible direct or indirect reasons why the works were composed, the commission that produced them, and precisely when and where they were given their first performance. Here are a few relatively reliable answers to these questions, which earlier Haydn scholars have been able to unearth from the obscurity of the past.

The Tageszeiten Symphonies may indeed have been written close to the time when the contract with Haydn was concluded and other musicians were engaged for the Esterházy court orchestra, among them the flautist and oboist Franz Sigl (contract of 7 May 1761) – according to Sonja Gerlach’s research, however, they came only after Symphonies nos.15 and 3,1 both of which have already been performed in the Haydn2032 series. A clue as to the date of composition is provided by the diary of Count Carl von Zinzendorf. On the evening of 22 May 1761 he attended a musical evening at the Palais Esterházy, where he heard a currently popular song, ‘Je n’aimais pas le tabac beaucoup’, which is quoted in the opening movement of Le Soir. (The air was written by no less a personage than Christoph Willibald Gluck for an opéra-comique called Le Diable à quatre, produced by the Théâtre Français of Vienna in 1759. It was a box-office hit and was revived on 11 April 1761, only a few weeks before the soirée in question.) Another factor that has been adduced is an astronomical event that caused much discussion in enlightened circles at the time and brought the capital of the Habsburg Empire an illustrious guest in the person of the French astronomer and cartographer César François Cassini de Thury, who seemed to be omnipresent in the Viennese aristocratic salons of the day: the transit of Venus that took place on 6 June 1761. The simultaneous observation and measurement of this phenomenon from various locations all over the globe was to provide scientists with information about the distance of the Earth from the Sun and ultimately – although only in later centuries – led to the exact determination of what we now call the astronomical unit. Since Esterházy family history was also characterised by a well-nigh hereditary interest in studying the heavens, this celestial spectacle may well have played a role in the choice of theme, especially as it was Paul Anton, once a student at the University of Leiden,2 who commissioned the composition of the Tageszeiten. And, according to Elaine Sisman, the trilogy evokes not only the motif of simple rural life dependent on the rhythm of nature, a widespread literary and pictural topos at the time, but also the diurnal course of the sun’s orbit, or the respective position of the heavenly body that grants us light and warmth in the morning, at noon and in the evening: ‘Haydn’s sun’, with which the music begins in eminently programmatic vein, ‘casts light on the worlds of science and religion and nature and art.’3

Of the three sunrises featured in Haydn’s compositional œuvre, the one in Le Matin is by far the earliest example. Like the comparable moments in Die Schöpfung (The Creation, premiered on 30 April 1798; instrumental prelude to Uriel’s recitative ‘In vollem Glanze steiget jetzt die Sonne strahlend auf’) and Die Jahreszeiten (The Seasons, premiered on 24 April 1801; ‘Sie steigt herauf, die Sonne’, chorus with soloists from ‘Der Sommer’), it is in D major (here, as in Die Schöpfung, it even begins on a single, unaccompanied D), works its way up the scale and cadences on the dominant at the dynamic climax.

The fact that Paul II Anton was not only a passionate lover of music – in both of the leading national styles of the time, Italian and French – but also a flautist of considerable talent was an open secret to his social circle. This also explains the quite untypical beginning of the Allegro that follows the sunrise in Haydn’s early symphonic work: the flute reveille (soon imitated by the oboes) is heard piano, and nature begins to stir in alternating forte and piano sections. When finally, instead of the expected entrance of the recapitulation, the horns rush in two bars ahead of the flute theme with a resounding unison, this is certainly to be understood as an allusion to another great passion which seems to be ‘running through the Prince’s mind’ here: the hunt, of course . . .

Hermann Kretzschmar averred that the brief Adagio which frames the ensuing Andante was intended to be a parody of a morning solmisation lesson, followed by humorous demonstrations of the schoolmaster’s virtuosity.4 Elaine Sisman strongly disagrees, seeing in this music the ‘rising of other heavenly bodies’ accompanying the Sun in the morning, such as the Moon or – as we have already mentioned – Venus: ‘Morning entails a banishment of night, a turn from Diana to Aurora, revealing the increasing irrelevance of the Moon – itself still usually present in the sky at dawn.’5 In this sense, Sisman suggests, the image of the singing teacher should probably be rectified; we should imagine Helios (or his successor Phoebus Apollo) with the sun-chariot accompanied by the Horae,6 a mythological theme that the Esterházy princes repeatedly placed on the ceiling frescoes of their magnificent palaces with a view to iconographical self-aggrandisement.

After the clouds trailing the Moon have been dispersed, a minuet is heard, in which the Sun excels as dancing master. The soloists on the dance floor once again include the flute, along with the oboes, the bassoon and finally, in the Trio, the viola and, for the first time in this cycle, the five-stringed violone, also known as the Wiener Quart-Terz-Violon. The concluding Allegro was described by H. C. Robbins Landon, in an apt metaphor, as ‘a brilliantly original way of pouring new wine into old bottles’, by which he meant that the compositional principle of the concerto grosso – the flute, the cello, even the two horns, but above all the violino principale, the part taken by Haydn himself, are awarded solo tasks to perform – appears filled with new life.7

While respectfully noting the objection once raised by Peter Gülke to the manifold attempts to construe the Tageszeiten Symphonies – ‘[Haydn] borrows the semblance of the wholly programmatic and [yet] writes music of such structural autonomy that there is really no need for the clues to concepts provided by the titles’8 – our reflections have now reached Le Midi, the only work of the cycle for which the composer’s manuscript has survived.

The opening movement of this C major symphony, with its slow introduction animated by broad gestures, prominent double-dotting borrowed from the ouverture à la française, and expansive twelve-part scoring, is certainly capable of conjuring up the idea of a sumptuous midday meal accompanied by table music. This is ‘confirmed’ to a certain extent in the ensuing Allegro by the concertante solo entrances of two solo violins, a solo cello, the two oboes and the bassoon, framed by rushing semiquaver figuration. But, all of a sudden, the festive mood changes. If the following pair of movements, consisting of a sombre instrumental recitative and a ‘liberating’ transition into a ‘richly figured dialogue between a solo violin and a solo cello’9 complete with fully written-out cadenza, is indeed to be understood as a parody of a ‘postprandial’ midday concert,10 then the audience would probably have had to be given a powerful aid to digestion. At any rate, Lukas Haselböck11 and, once again, Elaine Sisman have an alternative reading to offer: this alludes to the first movement of the ‘Summer’ concerto (L’estate) from Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, to which the recitative movement of Haydn’s symphony bears an ‘uncanny resemblance’.12 Both writers trace it back to a narrative tradition rooted in ancient poetry, according to which noon represents the hour when, ‘with often catastrophic consequences’, gods become visible to humans and the latter seek refuge when ‘light, heat, . . . silence and stasis become too oppressive’. It is precisely that place of refuge, ‘[t]he shady grove, the valley of purling streams and breezes [that] now appear more vividly, in the succeeding Adagio, with murmuring flutes in thirds’,13 preparing a pastorale-like backdrop for the protagonists, violin and cello. Thus it seems entirely fitting that the following minuet should be more rustic than courtly, while the Finale once again abandons itself to the skilful combination of symphonic and concertante styles, so that the special tonal charm of this Allegro stems from the contrasting juxtaposition of the violini concertati with the flute part, which is again reduced to a single instrument.

As has been noted above, Le Soir takes its theme from the ‘Tobacco Song’ in Gluck’s from Le Diable à quatre(the title of the eponymous opéra-comique means, in French, a turbulent character who makes a lot of noise and causes disorder). This is quoted in extenso and runs right through the opening movement, finally getting canonic treatment. And here we return to the question of what might originally have been the idea behind the commission to compose the Tageszeiten Symphonies. Daniel Heartz, who identified the Gluck quotation, developed the following thesis – starting out from the assumption that Haydn’s employer had fully informed him of his particular predilection in this regard:

Just as the high nobility around Maria Theresia was generally influenced by French culture, so too was Prince Anton Esterházy, who knew Paris and had built up a library of French books, scores and pictures, which was constantly supplied with the latest Parisian publications, for example with Rousseau’s writings (banned in Austria!) in 1761. It is not far-fetched to assume that he was also familiar with the works of François Boucher, which were in great demand at the time. Boucher painted a series of pictures called ‘The hours of the day of a lady of fashion’ [Les Heures du jour d'une femme élégante] for the Swedish ambassador to Paris in 1745. Another series, Points du Jour [Moments in the day], contains a picture called Le Soir with the subtitle ‘La Dame allant au Bal’[The lady going to the ball], accompanied by a quatrain commenting on it.

Did this fashionable lady perhaps even serve as a model for Margot? Margot, who goes out with the intention of dancing and – instead of the verse in the picture – sings her ‘Tobacco Song’. Finally . . . we recall that Haydn concludes his ‘Evening’ Symphony with La Tempesta. The background seems ambiguous: is it a thunderstorm, as invoked by the wicked Marquise, Margot’s antagonist? Is it the sky that masses in a thunderstorm – as an eventful finale at the end of the day?14

The notion of a company sitting together of an evening, enjoying singing, the beauty of the sunset, dance, and the comfort of a dwelling sheltered from the capricious weather that follows a hot summer’s day – all of this may very well have corresponded to the thoughts that ran through Haydn’s mind as he composed Hob. I:8. Perhaps it should be noted here how ingeniously he handles the traditional topoi of storm and tempest music in the Finale of Le Soir. Contrary to expectations, he is distinctly circumspect in his use of them, always anxious to give the soloists of his instrumental ensemble every conceivable freedom to present their virtuoso skills.

1 In Giuseppe Carpani’s biography Le Haydine we even read of another ‘solemn’ symphony already written for Paul Anton’s birthday on 22 April 1761, which Daniel Heartz surmised was the Symphony in C major Hob. I:25.

2 What is thought to have been the world’s first university observatory opened in Leiden (Netherlands) in 1633.

3 Elaine Sisman, ‘Haydn’s Solar Poetics: The Tageszeiten Symphonies and Enlightenment Knowledge’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, vol.66, no.1 (Spring 2013), pp.5-102, here p.91.

4 Hermann Kretzschmar, ‘Die Jugendsinfonien Joseph Haydns’, Jahrbuch der Musikbibliothek Peters, vol.15, 1908, pp.69-90, here p.84.

5 Sisman, p.55.

6 The Horai in Greek mythology, goddesses of the seasons and the natural divisions of time; their name is often translated as ‘the Hours’. (Translator’s note)

7 H. C. Robbins Landon, Haydn: Chronicle and Works, vol. 1, Haydn: The Early Years, 1732-1765 (London: Thames and Hudson, 1980), p.556.

8 Peter Gülke, ‘Haydns “Tageszeiten”-Sinfonien’, in id., Die Sprache der Musik. Essays zur Musik von Bach bis Holliger (Stuttgart, Weimar, Kassel: Bärenreiter/Metzler, 2001), pp.170-175, here p.170f.

9 Walter Lessing, Die Sinfonien von Joseph Haydn, vol. 1 (Baden-Baden: Südwestfunk, 1987), p.36.

10 Jürgen Braun, Sonja Gerlach, Sinfonien 1761 bis 1763. Joseph Haydn-Institut Köln (eds.): Joseph Haydn Werke, Series I, vol.3 (Munich: Henle, 1990), p.VIII.

11 Lukas Haselböck, ‘Vivaldi’s Le quattro stagioni und Haydn’s Tageszeiten-Sinfonien’, in Laurine Quetin, Gerold W. Gruber and Albert Gier (eds.), Joseph Haydn und Europa vom Absolutismus zur Aufklärung (= Musicorum 7; Tours: Université François Rabelais, 2009), pp.183-192.

12 Sisman, p.61.

13 Sisman, p.66.

14 Daniel Heartz, ‘Haydn und Gluck im Burgtheater um 1760: Der neue krumme Teufel, Le Diable à quatre und die Sinfonie “Le soir”’, in Christoph-Hellmut Mahling and Sigrid Wiesmann (eds.), Gesellschaft für Musikforschung. Bericht über den Internationalen Musikwissenschaftlichen Kongreß Bayreuth 1981 (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1984), pp.120-135, here pp.132, 135.

to the shop

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732–1809): Symphony No.8 G Major«Le Soir» Hob. I:8

Allegro molto / Andante / Menuet – Trio / La Tempesta. Presto

SYMPHONY NO.8 G MAJOR «LE SOIR» HOB. I:8 (Eisenstadt / Vienna 1761)

Time of creation: till 1767 [1761]

Allegro molto / Andante / Menuet – Trio / La Tempesta. Presto

by Christian Moritz-Bauer

The contract of employment ‘concluded for at least three years’, which the newly appointed ‘Vice – Capel – Meister’ Joseph Haydn signed on 1 May 1761 in the apartments of the Palais Esterházy on the Wallnerstraßein Vienna, bound him to a total of fourteen more or less strictly formulated clauses. For a salary of 400 Rhenish florins, he committed himself to take responsibility for the full range of activities of the Esterházy musical establishment in Vienna and the various princely dominions (with the exception of the ‘Chor – Musique’, i.e. the sacred choral music, in Eisenstadt) and to furnish new compositions as required by ‘His Serene Highness’. Furthermore, he should ‘appear daily . . . in the antechamber before and after midday, and inquire whether a high princely order for a musical performance has been given’.

A situation such as this seems to be recalled in the ‘Fifth Visit’ (interview), dated 11 May 1805, of Albert Christoph Dies’s Biographische Nachrichten von Joseph Haydn, which reports how his Prince once gave Haydn ‘the four times of day [Tageszeiten] as the subject of a composition’. Even if the resulting pieces were not four in number and were certainly not ‘in the form of quartets’ (as Dies states), they are without doubt among Haydn’s most frequently performed early works: the symphonies Le Matin, Le Midi and Le Soir.

While Le Midi has survived in an autograph dated 1761 that was preserved like a treasure in the composer’s personal collection throughout his life, only copies of its two sister works have come down to us, although their pertinent titles, mostly indicated in French, and their compositional characteristics leave no doubt that they belong to the same cycle.

Over the years, commentators have attempted to attach many a compositional template to Haydn’s Tageszeiten Symphonies. From the point of view of subject matter, there is, for example, theNeuer und sehr curios-Musicalischer Calender, Parthien-weiß mit 2 Violinen und Basso ò Cembalo in die zwölf Jahrs-Monat eingetheilet (New and very curious musical calendar in the style of suites, with two violins and basso or harpsichord, and divided into the twelve months of the year) written by Gregor Joseph Werner, Haydn’s superior at the time of the trilogy’s composition. Or a series of four ballets – entitled Le Matin, Le Midi, Le Soirand La Nuit – which sought to depict ‘rustic occupations and amusements over the four times of day’. These have been attributed to the composer Joseph Starzer and were performed in Laxenburg in 1755, with choreography by Franz Anton Hilverding. However, the corporation of music writers has declared the absolute favourite among possible models for Haydn’s triptych to be Antonio Vivaldi’s set of four violin concertos Le quattro stagioni, part of his op.8 collection Il cimento dell’armonia e dell’inventione (The contest between harmony and invention), which he dedicated to Count Wenzel von Morzin. (The latter, incidentally, was an uncle twice removed of Haydn’s first employer, Carl Joseph Franz von Morzin, and Vivaldi’s set of concertos also figures in the thematic catalogue of the Esterházy musical collections compiled under Prince Paul Anton around 1740.)

An additional area of discussion concerns the possible direct or indirect reasons why the works were composed, the commission that produced them, and precisely when and where they were given their first performance. Here are a few relatively reliable answers to these questions, which earlier Haydn scholars have been able to unearth from the obscurity of the past.

The Tageszeiten Symphonies may indeed have been written close to the time when the contract with Haydn was concluded and other musicians were engaged for the Esterházy court orchestra, among them the flautist and oboist Franz Sigl (contract of 7 May 1761) – according to Sonja Gerlach’s research, however, they came only after Symphonies nos.15 and 3,1 both of which have already been performed in the Haydn2032 series. A clue as to the date of composition is provided by the diary of Count Carl von Zinzendorf. On the evening of 22 May 1761 he attended a musical evening at the Palais Esterházy, where he heard a currently popular song, ‘Je n’aimais pas le tabac beaucoup’, which is quoted in the opening movement of Le Soir. (The air was written by no less a personage than Christoph Willibald Gluck for an opéra-comique called Le Diable à quatre, produced by the Théâtre Français of Vienna in 1759. It was a box-office hit and was revived on 11 April 1761, only a few weeks before the soirée in question.) Another factor that has been adduced is an astronomical event that caused much discussion in enlightened circles at the time and brought the capital of the Habsburg Empire an illustrious guest in the person of the French astronomer and cartographer César François Cassini de Thury, who seemed to be omnipresent in the Viennese aristocratic salons of the day: the transit of Venus that took place on 6 June 1761. The simultaneous observation and measurement of this phenomenon from various locations all over the globe was to provide scientists with information about the distance of the Earth from the Sun and ultimately – although only in later centuries – led to the exact determination of what we now call the astronomical unit. Since Esterházy family history was also characterised by a well-nigh hereditary interest in studying the heavens, this celestial spectacle may well have played a role in the choice of theme, especially as it was Paul Anton, once a student at the University of Leiden,2 who commissioned the composition of the Tageszeiten. And, according to Elaine Sisman, the trilogy evokes not only the motif of simple rural life dependent on the rhythm of nature, a widespread literary and pictural topos at the time, but also the diurnal course of the sun’s orbit, or the respective position of the heavenly body that grants us light and warmth in the morning, at noon and in the evening: ‘Haydn’s sun’, with which the music begins in eminently programmatic vein, ‘casts light on the worlds of science and religion and nature and art.’3

Of the three sunrises featured in Haydn’s compositional œuvre, the one in Le Matin is by far the earliest example. Like the comparable moments in Die Schöpfung (The Creation, premiered on 30 April 1798; instrumental prelude to Uriel’s recitative ‘In vollem Glanze steiget jetzt die Sonne strahlend auf’) and Die Jahreszeiten (The Seasons, premiered on 24 April 1801; ‘Sie steigt herauf, die Sonne’, chorus with soloists from ‘Der Sommer’), it is in D major (here, as in Die Schöpfung, it even begins on a single, unaccompanied D), works its way up the scale and cadences on the dominant at the dynamic climax.

The fact that Paul II Anton was not only a passionate lover of music – in both of the leading national styles of the time, Italian and French – but also a flautist of considerable talent was an open secret to his social circle. This also explains the quite untypical beginning of the Allegro that follows the sunrise in Haydn’s early symphonic work: the flute reveille (soon imitated by the oboes) is heard piano, and nature begins to stir in alternating forte and piano sections. When finally, instead of the expected entrance of the recapitulation, the horns rush in two bars ahead of the flute theme with a resounding unison, this is certainly to be understood as an allusion to another great passion which seems to be ‘running through the Prince’s mind’ here: the hunt, of course . . .

Hermann Kretzschmar averred that the brief Adagio which frames the ensuing Andante was intended to be a parody of a morning solmisation lesson, followed by humorous demonstrations of the schoolmaster’s virtuosity.4 Elaine Sisman strongly disagrees, seeing in this music the ‘rising of other heavenly bodies’ accompanying the Sun in the morning, such as the Moon or – as we have already mentioned – Venus: ‘Morning entails a banishment of night, a turn from Diana to Aurora, revealing the increasing irrelevance of the Moon – itself still usually present in the sky at dawn.’5 In this sense, Sisman suggests, the image of the singing teacher should probably be rectified; we should imagine Helios (or his successor Phoebus Apollo) with the sun-chariot accompanied by the Horae,6 a mythological theme that the Esterházy princes repeatedly placed on the ceiling frescoes of their magnificent palaces with a view to iconographical self-aggrandisement.

After the clouds trailing the Moon have been dispersed, a minuet is heard, in which the Sun excels as dancing master. The soloists on the dance floor once again include the flute, along with the oboes, the bassoon and finally, in the Trio, the viola and, for the first time in this cycle, the five-stringed violone, also known as the Wiener Quart-Terz-Violon. The concluding Allegro was described by H. C. Robbins Landon, in an apt metaphor, as ‘a brilliantly original way of pouring new wine into old bottles’, by which he meant that the compositional principle of the concerto grosso – the flute, the cello, even the two horns, but above all the violino principale, the part taken by Haydn himself, are awarded solo tasks to perform – appears filled with new life.7

While respectfully noting the objection once raised by Peter Gülke to the manifold attempts to construe the Tageszeiten Symphonies – ‘[Haydn] borrows the semblance of the wholly programmatic and [yet] writes music of such structural autonomy that there is really no need for the clues to concepts provided by the titles’8 – our reflections have now reached Le Midi, the only work of the cycle for which the composer’s manuscript has survived.

The opening movement of this C major symphony, with its slow introduction animated by broad gestures, prominent double-dotting borrowed from the ouverture à la française, and expansive twelve-part scoring, is certainly capable of conjuring up the idea of a sumptuous midday meal accompanied by table music. This is ‘confirmed’ to a certain extent in the ensuing Allegro by the concertante solo entrances of two solo violins, a solo cello, the two oboes and the bassoon, framed by rushing semiquaver figuration. But, all of a sudden, the festive mood changes. If the following pair of movements, consisting of a sombre instrumental recitative and a ‘liberating’ transition into a ‘richly figured dialogue between a solo violin and a solo cello’9 complete with fully written-out cadenza, is indeed to be understood as a parody of a ‘postprandial’ midday concert,10 then the audience would probably have had to be given a powerful aid to digestion. At any rate, Lukas Haselböck11 and, once again, Elaine Sisman have an alternative reading to offer: this alludes to the first movement of the ‘Summer’ concerto (L’estate) from Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, to which the recitative movement of Haydn’s symphony bears an ‘uncanny resemblance’.12 Both writers trace it back to a narrative tradition rooted in ancient poetry, according to which noon represents the hour when, ‘with often catastrophic consequences’, gods become visible to humans and the latter seek refuge when ‘light, heat, . . . silence and stasis become too oppressive’. It is precisely that place of refuge, ‘[t]he shady grove, the valley of purling streams and breezes [that] now appear more vividly, in the succeeding Adagio, with murmuring flutes in thirds’,13 preparing a pastorale-like backdrop for the protagonists, violin and cello. Thus it seems entirely fitting that the following minuet should be more rustic than courtly, while the Finale once again abandons itself to the skilful combination of symphonic and concertante styles, so that the special tonal charm of this Allegro stems from the contrasting juxtaposition of the violini concertati with the flute part, which is again reduced to a single instrument.

As has been noted above, Le Soir takes its theme from the ‘Tobacco Song’ in Gluck’s from Le Diable à quatre(the title of the eponymous opéra-comique means, in French, a turbulent character who makes a lot of noise and causes disorder). This is quoted in extenso and runs right through the opening movement, finally getting canonic treatment. And here we return to the question of what might originally have been the idea behind the commission to compose the Tageszeiten Symphonies. Daniel Heartz, who identified the Gluck quotation, developed the following thesis – starting out from the assumption that Haydn’s employer had fully informed him of his particular predilection in this regard:

Just as the high nobility around Maria Theresia was generally influenced by French culture, so too was Prince Anton Esterházy, who knew Paris and had built up a library of French books, scores and pictures, which was constantly supplied with the latest Parisian publications, for example with Rousseau’s writings (banned in Austria!) in 1761. It is not far-fetched to assume that he was also familiar with the works of François Boucher, which were in great demand at the time. Boucher painted a series of pictures called ‘The hours of the day of a lady of fashion’ [Les Heures du jour d'une femme élégante] for the Swedish ambassador to Paris in 1745. Another series, Points du Jour [Moments in the day], contains a picture called Le Soir with the subtitle ‘La Dame allant au Bal’[The lady going to the ball], accompanied by a quatrain commenting on it.

Did this fashionable lady perhaps even serve as a model for Margot? Margot, who goes out with the intention of dancing and – instead of the verse in the picture – sings her ‘Tobacco Song’. Finally . . . we recall that Haydn concludes his ‘Evening’ Symphony with La Tempesta. The background seems ambiguous: is it a thunderstorm, as invoked by the wicked Marquise, Margot’s antagonist? Is it the sky that masses in a thunderstorm – as an eventful finale at the end of the day?14

The notion of a company sitting together of an evening, enjoying singing, the beauty of the sunset, dance, and the comfort of a dwelling sheltered from the capricious weather that follows a hot summer’s day – all of this may very well have corresponded to the thoughts that ran through Haydn’s mind as he composed Hob. I:8. Perhaps it should be noted here how ingeniously he handles the traditional topoi of storm and tempest music in the Finale of Le Soir. Contrary to expectations, he is distinctly circumspect in his use of them, always anxious to give the soloists of his instrumental ensemble every conceivable freedom to present their virtuoso skills.

1 In Giuseppe Carpani’s biography Le Haydine we even read of another ‘solemn’ symphony already written for Paul Anton’s birthday on 22 April 1761, which Daniel Heartz surmised was the Symphony in C major Hob. I:25.

2 What is thought to have been the world’s first university observatory opened in Leiden (Netherlands) in 1633.

3 Elaine Sisman, ‘Haydn’s Solar Poetics: The Tageszeiten Symphonies and Enlightenment Knowledge’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, vol.66, no.1 (Spring 2013), pp.5-102, here p.91.

4 Hermann Kretzschmar, ‘Die Jugendsinfonien Joseph Haydns’, Jahrbuch der Musikbibliothek Peters, vol.15, 1908, pp.69-90, here p.84.

5 Sisman, p.55.

6 The Horai in Greek mythology, goddesses of the seasons and the natural divisions of time; their name is often translated as ‘the Hours’. (Translator’s note)

7 H. C. Robbins Landon, Haydn: Chronicle and Works, vol. 1, Haydn: The Early Years, 1732-1765 (London: Thames and Hudson, 1980), p.556.

8 Peter Gülke, ‘Haydns “Tageszeiten”-Sinfonien’, in id., Die Sprache der Musik. Essays zur Musik von Bach bis Holliger (Stuttgart, Weimar, Kassel: Bärenreiter/Metzler, 2001), pp.170-175, here p.170f.

9 Walter Lessing, Die Sinfonien von Joseph Haydn, vol. 1 (Baden-Baden: Südwestfunk, 1987), p.36.

10 Jürgen Braun, Sonja Gerlach, Sinfonien 1761 bis 1763. Joseph Haydn-Institut Köln (eds.): Joseph Haydn Werke, Series I, vol.3 (Munich: Henle, 1990), p.VIII.

11 Lukas Haselböck, ‘Vivaldi’s Le quattro stagioni und Haydn’s Tageszeiten-Sinfonien’, in Laurine Quetin, Gerold W. Gruber and Albert Gier (eds.), Joseph Haydn und Europa vom Absolutismus zur Aufklärung (= Musicorum 7; Tours: Université François Rabelais, 2009), pp.183-192.

12 Sisman, p.61.

13 Sisman, p.66.

14 Daniel Heartz, ‘Haydn und Gluck im Burgtheater um 1760: Der neue krumme Teufel, Le Diable à quatre und die Sinfonie “Le soir”’, in Christoph-Hellmut Mahling and Sigrid Wiesmann (eds.), Gesellschaft für Musikforschung. Bericht über den Internationalen Musikwissenschaftlichen Kongreß Bayreuth 1981 (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1984), pp.120-135, here pp.132, 135.

to the shop

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791): Serenade D Major «Serenata notturna» KV 239

Marcia. Maestoso / Menuetto – Trio (Menuetto 2do) / Rondeau. Allegretto – Adagio – Allegro

W. A. MOZART: SERENADE IN D MAJOR «SERENATA NOTTURNA» KV 239 (Salzburg in January 1776)

Marcia. Maestoso / Menuetto – Trio (Menuetto 2do) / Rondeau. Allegretto – Adagio – Allegro

by Christian Moritz-Bauer

‘Mozart’s name has come to symbolise the history of the serenade and divertimento’, begins an article by Thomas Schipperges in the Mozart-Handbuch jointly published by Bärenreiter and Metzler in 2006. And he goes on to state that ‘[w]ithin Mozart’s own oeuvre, [this] genre – music lying outside the chamber or the church, the theatre or the ballroom – is regarded as peripheral’, only to emphasise immediately that although much has been written ‘about specific questions of terminology and dating, performing circumstances and practice’, behind ‘the philological detail . . . the individual compositions, . . . the music [itself] has usually taken a back seat’.1

In the case of the work that has become known to music history as the ‘Serenata notturna’ and is still found more or less regularly on concert programmes today, it already seems hard enough to answer the ‘specific questions’ mentioned by Schipperges. We are frequently told, for example, that the heading in the autograph, which actually reads ‘Serenada [sic] notturna’, and the indication of the composer and date ‘di Wolfgango Amadeo Mozart / nel gennaio 1776’ are in the hand of Leopold Mozart. Moreover, the piece is said to have been intended as outdoor music, but its scoring without wind instruments and the period of its composition suggest rather that it was written for indoor performance, possibly even as New Year’s music. To all intents and purposes, though, it is generally assumed that we have no idea of the precise circumstances of its first performance and the related question of what prompted its composition.

The first correction to be made to the traditional narrative of K239 is the supposed title of the work. As we can read in Ernst Hintermaier’s 1988 Critical Report to theNeue Mozart-Ausgabe edition of the score published by Günther Haußwald in 1962,2 this did not actually originate with Leopold at all, but was added by a certain Franz Gleissner – a fact that has been purely and simply ignored by prominent Mozart scholars right down to the present day. Gleissner, a court musician to the Elector of Bavaria, composer and co-inventor of lithographic printing, worked in 1800 and 1801 with the publishing house of Johann Anton André in Offenbach, compiling a list arranged by genre of compositions that André had purchased from Mozart’s widow Constanze a year earlier. This is probably how the originally untitled work came to acquire its posthumous name, a combination of the terms ‘serenade’ and ‘notturno’. (The Notturno for four orchestras K286, often regarded as a sister work to K239, whose salient features of scoring for several instrumental groups and three-movement structure it shares and whose autograph was lost in the turmoil of the Second World War, may well have been ‘christened’ by Gleissner in similar fashion.)

Furthermore, there is good reason to surmise that the work was not intended – like the majority of Mozart’s serenades and divertimenti – as open-air music or Huldigungsmusik to be played in homage to a higher-ranking person or group, or sometimes one or more friends or relatives of the composer, and certainly not as New Year’s music. Rather, the occasion for the composition of the Serenata notturna seems to lie in the direction of the Redouten or masked balls held at Salzburg’s Town Hall, then situated on the Kranzlmarkt. These took place every Wednesday and Sunday between Candlemas and Ash Wednesday, and were regularly and enthusiastically attended by both upper- and middle-class citizens, including Leopold and Wolfgang Mozart. Ferdinand von Schidenhofen, Salzburg court councillor, district chancellor and friend of the Mozart family, reports in his diary:

Wednesday 14 February [1776].

. . . In the evening . . . I went to [Johann von] Geÿer’s residence, where I was awaited by the company who were presenting a [pantomime depicting a] French recruitment parade at the masked ball. We arrived at half past nine. Herr Meisner went first as drum major, followed by six musicians. Then Master of the Horse [Leopold, Count] Kuenburg as a corporal, and General [Franz Johann Nepomuk Anton Felix] Count Arco, Fortress Commander Count [Johann Gottfried] Lützow, Baron [Polycarp von] Lilien, Herr Schmid, Herr [Ferdinand] von Geÿer Fähndrich, and Count [Anton Willibald von] Wolfegg as commanding officer. Then [Wolf Joseph,] Count Überacker, Captain [Felix Johann von] Freitag, and myself as recruits, Captain Riser as a prisoner and Count Wicka as a sutler. In addition, [Johann Rudolph,] Count Czernin performed a rival recruitment parade for the cavalry, accompanied by Baron [Franz Christoph von] Lehrbach, the pages and others. I went home at three o’clock, by which time it was too crowded for dancing because 410 people were there.3

It is difficult to imagine how a parade of the kind Schidenhofen put on along with his fellow Salzburgers and in front of several hundred ball guests that evening, a week before the beginning of Lent in 1776, could have taken place without suitable music to accompany it. In a context such as this, several of the conspicuous features of the work we have been discussing suddenly become self-explanatory, from the instrumental forces it calls for (a solo ‘serenade quartet’ is juxtaposed with a larger string group that acts as a chorus, commenting on and punctuating the material presented by the quartet, and underpinned by a timpanist who impels the musical action) to the consistently unusual sequence of movements. Marcia: a march-like motif is heard, but only as a signal for the protagonists of our little carnivalesque game to form ranks. As early as the third bar, a charming entrance by the solo quartet belies the apparent seriousness of the scene and is enthusiastically cheered by the assembled orchestral tutti. After all, the ‘recruiting sergeants’ are French, seeking soldiers to take part in the American War of Independence. The whole movement thrives on the interplay of the two groups and their motifs, interspersed on occasion with soft timpani strokes and string pizzicati that disseminate a mysterious nocturnal mood.

As befits the opening of a masked ball, a Menuetto follows. At first it seems a little stiff, but its middle section – which Mozart entitled ‘Menuetto 2do’ after the French model – is characterised by a relaxed triplet movement performed by the serenade quartet alone.

The pretend ‘company’ soon begins its retreat with a compositionally ingenious Rondeau, embellished by several interpolations that produce a thoroughly comical effect, including an Adagio recitative and an accelerated return of the movement’s theme with pizzicato/coll’arco contrasts. At the end, with the final roll of drums, the actors melt into the crowd of maskers.

1 Thomas Schipperges, ‘Mozart und die Tradition gesellschaftsgebundener Unterhaltungsmusik im 18. Jahrhundert’, in Silke Leopold (ed.), Mozart-Handbuch (Stuttgart, Weimar, Kassel: Bärenreiter/Metzler, 2005), pp.562-564, here p.562.

2 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Neue Ausgabe sämtlicher Werke. Serie IV Orchesterwerke, Werkgruppe 12: Kassationen, Serenaden und Divertimenti für Orchester, vol.3: Full Score, edited and introduced by Günter Haußwald (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1962); Critical Report by Ernst Hintermaier (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1988).

3 Hannelore und Rudolph Angermüller with Günther G. Bauer (eds.), Joachim Ferdinand von Schidenhofen, ein Freund der Mozarts. Die Tagebücher des Salzburger Hofrats (Bad Honnef: Bock, 2006), p.136.

to the shop

Line-up

Il Giardino Armonico

Giovanni Antonini, conductor

- Line-up Orchestra

1st violin Stefano Barneschi, Fabrizio Haim Cipriani, Ayako Matsunaga, Liana Mosca, Carlo Lazzaroni, Dmitry Smirnov

2nd violin Marco Bianchi, Angelo Calvo, Francesco Colletti, Maria Cristina Vasi, Chiara Zanisi

Viola Renato Burchese, Alice Bisanti, Carlo De Martini

Cello Paolo Beschi, Elena Russo, Marcello Scandelli

Doublebass Giancarlo De Frenza, Stefan Preyer

Flute Marco Brolli, Eva Oertle

Oboe Thomas Meraner, Molly Marsh

French Horn Johannes Hinterholzer, Edward Deskur

Bassoon Michele Fattori

Timpani Riccardo Balbinutti

Past concerts

Paris

Wednesday, 16.01.2019

Louvre Paris

Vienna

Thursday, 17.01.2019

Musikverein Vienna

Rome

Wednesday, 23.01.2019

Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Rome

Basel

Thursday, 24.01.2019, 19.30 pm

Martinskirche Basel

Haydn Lounge: 18.30 pm, with Giovanni Antonini and Andrea Scartazzini

Haydn Reading: 19.00 Uhr, with Margriet de Moor

Concert: 19.30 pm (Haydn Soup during interval)

Biographies

Orchestra

Il Giardino Armonico

Orchestra

Founded in 1985 and conducted by Giovanni Antonini, has been established as one of the world’s leading period instrument ensembles, bringing together musicians from Europe’s relevant music institutions. The ensemble’s repertoire mainly focuses on the 17th and 18th century. Depending on the demands of each program, the group consists of three up to thirty musicians.

Il Giardino Armonico is regularly invited to festivals all over the world performing in the most important concert halls, and has received high acclaim for both concerts and opera productions, like Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo, Vivaldi’s Ottone in Villa Händel’s Agrippina, Il Trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno, La Resurrezione and finally Giulio Cesare in Egitto with Cecilia Bartoli during the 2012 edition of the Salzburg Whitsun and Summer Festival.

Beside that, Il Giardino Armonico sustains an intense recording activity. After many years as an exclusive group of Teldec Classics achieving several major awards for its recordings of works by Vivaldi and the other 18th century composers, the group had an exclusive agreement with Decca/ L’Oiseau-Lyre recording Händel’s Concerti Grossi Op. VI and the cantata Il Pianto di Maria with Bernarda Fink.

The group also released on Naïve La Casa del Diavolo, Vivaldi cello Concertos with Christophe Coin, and the opera Ottone in Villa winning the Diapason d’Or in 2011. On the label Onyx Vivaldi violin Concertos with Viktoria Mullova.

In 2009 a new cooperation with Cecilia Bartoli led to the project Sacrificium (Decca), Platinum Album in France and Belgium and prized by the Grammy Award.

Again on Decca Alleluia (March 2013) and Händel in Italy (October 2015) with Julia Lezhneva, acclaimed by public and critics.

The group published Serpent & Fire with Anna Prohaska (Alpha Classics – Outhere music group, 2016) winning the ICMA “baroque vocal” in 2017.

The recording of five Mozart Violin Concertos with Isabel Faust (Harmonia Mundi, 2016) stands as the result of the prestigious cooperation with the great violinist.

Il Giardino Armonico is part of the twenty-year project Haydn2032 for which the Haydn Foundation has been created in Basel to support both the recording project of the complete Haydn Symphonies (Alpha Classic) and a series of concerts in various European cities, with thematic programs focused on this fascinating repertoire. In November 2014 the first album titled La Passione has been published and won the Echo Klassik award in 2015. Il Filosofo, issued in 2015, has been “CHOC of the year” by Classica. The third one Solo e Pensoso has been released in August 2016, and the forth Il Distratto in March 2017.

The last volumes of the Haydn2032 project, as well as Telemann (Alpha Classics, November 2016) are available as CD and LP too. Telemann won the Diapason d’Or in January 2017.

Furthermore the ensemble worked with such acclaimed soloists as Giuliano Carmignola, Sol Gabetta, Katia and Marielle Labèque, Viktoria Mullova, and Giovanni Sollima.

Conductor

Giovanni Antonini

Conductor

Born in Milan, Giovanni studied at the Civica Scuola di Musica and at the Centre de Musique Ancienne in Geneva. He is a founder member of the Baroque ensemble “Il Giardino Armonico”, which he has led since 1989. With this ensemble, he has appeared as conductor and soloist on the recorder and Baroque transverse flute in Europe, United States, Canada, South America, Australia, Japan and Malaysia. He is Artistic Director of Wratislavia Cantans Festival in Poland and Principal Guest Conductor of Mozarteum Orchester and Kammerorchester Basel.

He has performed with many prestigious artists including Cecilia Bartoli, Kristian Bezuidenhout, Giuliano Carmignola, Isabelle Faust, Sol Gabetta, Sumi Jo, Viktoria Mullova, Katia and Marielle Labèque, Emmanuel Pahud and Giovanni Sollima. Renowned for his refined and innovative interpretation of the classical and baroque repertoire, Antonini is also a regular guest with Berliner Philharmoniker, Concertgebouworkest, Tonhalle Orchester, Mozarteum Orchester, Leipzig Gewandhausorchester, London Symphony Orchestra and Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

His opera productions have included Handel’s Giulio Cesare and Bellini’s Norma with Cecilia Bartoli at Salzburg Festival. In 2018 he conducted Orlando at Theater an der Wien and returned to Opernhaus Zurich for Idomeneo. In the 21/22 season he will guest conduct the Konzerthaus Orchester Berlin, Stavanger Symphony, Anima Eterna Bruges and the Symphonieorchester de Bayerischer Rundfunks. He will also direct Cavalieri’s opera Rappresentatione di Anima, et di Corpo for Theatre an der Wien and a ballet production of Haydn’s Die Jahreszeiten for Wiener Staatsballett with the Wiener Philharmoniker.

With Il Giardino Armonico, Giovanni has recorded numerous CDs of instrumental works by Vivaldi, J.S. Bach (Brandenburg Concertos), Biber and Locke for Teldec. With Naïve he recorded Vivaldi’s opera Ottone in Villa, and, with Il Giardino Armonico for Decca, has recorded Alleluia with Julia Lezhneva and La morte della Ragione, collections of sixteenth and seventeenth century instrumental music. With Kammerorchester Basel he has recorded the complete Beethoven Symphonies for Sony Classical and a disc of flute concertos with Emmanuel Pahud entitled Revolution for Warner Classics. In 2013 he conducted a recording of Bellini’s Norma for Decca in collaboration with Orchestra La Scintilla.

Antonini is artistic director of the Haydn 2032 project, created to realise a vision to record and perform with Il Giardino Armonico and Kammerorchester Basel, the complete symphonies of Joseph Haydn by the 300th anniversary of the composer’s birth. The first 12 volumes have been released on the Alpha Classics label with two further volumes planned for release every year.

Videos

Recordings

VOL. 10 _LES HEURES DU JOUR

CD

Giovanni Antonini, Il Giardino Armonico

Symphonies No.6 "Le Matin", No.7 "Le Midi" and No.8 "Le Soir"

W. A. Mozart: Serenade in D major «Serenata notturna»

Available at:

Bider&Tanner, Basel

Outhere Music

Download / Stream

Jérôme Sessini / Magnum Photos

Biography

Photographer, Magnum Photos

Jérôme Sessini

Photographer, Magnum Photos

Jérôme Sessini (b 1968) is a member of Magnum Photos since 2016. He discovered his passion for photography through a photographer friend who showed him books on documentary photography. He began developing his own practice by capturing the people, landscapes and daily life of his native region in the east of France.

When he arrived in Paris, he was first hired by the photo agency Gamma to cover the ongoing conflict in Kosovo. He has since covered many international current events, from the second Intifada and the war in Iraq to the uprising in Libya and the conflicts in Syria. His work has been exhibited in a number of institutions and has been published in many prestigious newspapers and magazines, as well as receiving much international acclaim.

In 2008, he began his project So far from God, too close to the US, which plunges into the war between drug cartels in Mexico. This direct confrontation with violence led him to articulate a conviction that is at the heart of his work: “It is always the ordinary fellows who lose, be it in Iraq, Mexico or France.”

The same year, he photographed Cuba after Fidel Castro’s withdrawal from politics. In 2011, he covered the uprising in Lybia, photographing from the rebels’ point of view. In 2012 and 2013, he was in Aleppo, Syria. In February 2014, he seized the final fight for Euromaidan in Kiev, Ukraine. Those three series have in common an incredibly closeness to the fighters, the photographer seeming to share their hardships and emotions.

A hush then falls outside. A hush as deafening and illogical as a symphony silenced just as the orchestra was raring to go. Napoleon has been persuaded by the dying man’s friends. He didn’t even need much persuading. The occupier, as would any right-minded soul familiar with the name of the world-famous man of music, has ordered that Kleine Steingasse be spared the ravages of war.

Excerpt from the essay "Joseph Haydn dies" by Margriet de Moor

The essay "Joseph Haydn dies" by Margriet de Moor will be published in the vinyl edition vol. 10.

Biography

Writer

Margriet de Moor

Writer

One of the most prominent Dutch authors of her generation, Margriet de Moor studied piano and voice before she turned her talents to writing. Her first novel, Erst grau dann weiß dann blau (Hanser, 1993) was an immediate bestseller and garnered sensational success. Her novels and stories have been translated to languages all over the world. Her works are published by Hanser and include highlights such as Die Verabredung (The Meeting, novel, 2000), Der Jongleur (The Troubadour, A Divertimento, 2008), Der Maler und das Mädchen (The Painter and the Girl, novel, 2011), Mélodie d'amour (novel, 2014), Schlaflose Nacht (Sleepless Night, 2016) and Von Vögeln und Menschen (Of Birds and Humans, novel, 2018). Margriet de Moor lives in Amsterdam.