NO.5 __L'HOMME DE GÉNIE

Basel Chamber Orchestra

Giovanni Antonini, conductor

Eva Gesine Baur, writer

Stuart Franklin, photographer

Symphonies No.19, No.80 and No.81

J. M. Kraus: Symphony in c Minor VB 142

Program

Joseph Haydn (1732–1809): Symphony No.81 in G Major, Hob. I:81 (1784)

Vivace / Andante / Menuet. Allegretto – Trio / Finale. Allegro ma non troppo

SYMPHONY NO.81 IN G MAJOR HOB. I:81 (1763)

Time of creation: [till 8.11.1784]

Vivace / Andante / Menuet. Allegretto – Trio / Finale. Allegro ma non troppo

Christian Moritz-Bauer

«Haydn does not always succeed in combining the uncomplicated, the popular and the artificial.»

(Michael Walter, Haydns Sinfonien. Ein musikalischer Werkführer. Munich: C. H. Beck, 2007, p.84)

«[T]here are no surprising or dramatic gestures, little use of the minor mode, no overt displays of a learned style, and all of it is accessible upon first hearing . . . This work would be easily received by the elite group . . . who could concern themselves with going to concerts or private entertainments»

(A. Peter Brown, The Symphonic Repertoire Vol. II. The First Golden Age of the Viennese Symphony: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert.Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002, p.207)

«A. Peter Brown, The Symphonic Repertoire Vol. II. The First Golden Age of the Viennese Symphony: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002), p.207»

(H.C. Robbins Landon: Haydn: Chronicle and Works. Vol. 2: Haydn at Eszterháza, 1766-1790. London: Thames and Hudson, 1978, p.567)

«It is now rare when the odd and the eccentric (still as frequent as ever in his work) are not transfigured by poetry [as in the] little-appreciated Symphony no.81.»

(Charles Rosen, The Classical Style. Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven. Second edition. London: Faber and Faber, 1976, p.157)

As may be seen from the quotations above, opinions have always diverged widely concerning the Symphony in G major Hob. I:81, with respect not only to its compositional qualities, but also to its significance within the output of Joseph Haydn.

Standing at the threshold between the so-called «Sturm und Drang» or «theatre symphonies» of the late 1760s and 1770s and the period of the «Paris» and «London» symphonies, it originally formed the opening work in the composer’s second group of symphonies aimed at an international audience, and was first published as such by the Viennese firm of Artaria in March 1785.

What was intended to comply with the demands of the market for entertainment and to be playable without particular difficulties by performing musicians from far and wide had to be reconciled with the demands the composer had imposed on himself, which had grown ever more stringent over the years: what a challenge! And it is precisely that challenge that Haydn attempts to meet here with surprisingly innovative compositional elements, which are even utilised in transgressive fashion at times.

Naturally, a favourite place of the composer’s for showing his paces was the opening of the work, for which he came up, in the present case, with a gambit of well-nigh inspired simplicity. From a powerful tutti chord, of which soon nothing is left but the residue of a sound wave, a drum bass emerges in the cellos, mysterious in its fragility. Its softly throbbing repeated Gs are accompanied by a superimposed F in the second violins and an appoggiatura motif in the firsts that further obscures the harmonic centre. When the first violins do finally play the leading note that clarifies the key, and then regain ground contact by means of a gently undulating quaver motion, the whole body of strings quite unexpectedly slips into the dominant, D major. A classic false start? All right then: as you were! Try again!

Is it the early entry of the violas that gives the loosely attached kaleidoscope of motifs the necessary stability in the restatement that follows? What counts is success – and this is exactly what is promised by a forte section, emphasised by powerful rhythmic contours, which appears towards the end of the next period on a harmonic framework underpinned by tutti chords. A further thematic idea, characterised by quaver rests and chromatic melodic progression, also makes good use of that harmonic scheme.

Here, if no earlier, our master moves into the zone where his target audience of the time could still – just – follow him; and so he can risk playing his well-tried game of sowing deliberate confusion once more. Right at the end of the movement, though, the listeners’ prayers for something straightforward are finally heard, and they are propitiated with a full reprise of the opening theme, which ends in a simple closing cadence.

The friendly, relaxed mood that has finally made its appearance here is prolonged for the audience’s enjoyment in the ensuing Andante, a siciliana theme followed by three variations, outstanding among them a contrasting, centrally placed interlude in Dorian D minor.

After a Menuetto of rustic cast and a solo bassoon-led Trio with an exotic-sounding sideslip into the minor, the Finale enters with the most varied rhythmic impulses imaginable. This Allegro frustrates listeners’ expectations, not only in its tone, which seems more appropriate to a first movement than to a finale, but also because of the deceleratory postscript to the tempo marking (‘ma non troppo’). However, there is one good thing about Haydn’s teasing: the danger of losing sight of the trajectory of the monothematic melodic line, with all its part-crossings, motivic variations and changing accentuations, or of not being able to follow it with ear and mind alike, is clearly diminished!

to the shop

Joseph Martin Kraus (1756–1792): Symphony in c Minor VB 142 (1783?)

Larghetto – Allegro / Andante / Allegro assai

SYMPHONY IN C MINOR VB 142 (Vienna, 1783)

Larghetto – Allegro / Andante / Allegro assai

Christian Moritz-Bauer

Joseph Martin Kraus was born in Miltenberg am Main on 20 June 1756, to Johann Bernhard Kraus, an official of the Electorate of Mainz, and Anna Dorothea, née Schmitt, who came from a dynasty of master builders. In the course of his humanistic education at the Jesuit College in Mannheim, he came into contact at an early age with the artistic community resident at the «Court of the Muses» headed by the Palatine Elector Carl Theodor, at a time when its special pride and joy was the court orchestra, which enjoyed an almost legendary reputation throughout Europe. After commencing studies in philosophy and law in Mainz (January 1773), where his youthful, impetuous mind first conceived notions of social and political freedom, he soon transferred to the University of Erfurt. There he took lessons from Bach’s former student Johann Christian Kittel, of which Kraus made good use to compose sacred works during the ensuing year-long interruption of his studies, which he was obliged to spend in Buchen im Odenwald, now the family home, because of a campaign of defamation against his father. Under the influence of Heinrich Leopold Wagner’s Neue Versuch über die Schauspielkunst (New essay on the dramatic arts, translated from the French Essai sur l’art dramatique of Louis-Sébastien Mercier), and in order to express in writing his resentment of the absolutist authorities, he swiftly penned Tolon, a spoken tragedy in three acts. Its language, which makes conspicuous use of the tone of the Sturm und Drang literary movement, was subsequently also to fill the letters of this critical son of the bourgeoisie, who moved to Göttingen in November 1776 to resume his studies there.

In the university town in Lower Saxony, Kraus came into contact with the «Hainbund» (literally, «League of the grove»), a group of students active in the literary field, including Carl Friedrich Cramer, Friedrich Hahn, Anton Leisewitz, Heinrich Voss, the cousins Johann and Gottlieb Miller, and the brothers Friedrich Leopold and Christian zu Stolberg-Stolberg. What the Hainbündler had in common was their veneration of Klopstock and Bürger, their intense love of fatherland and freedom, and their passionate rejection of the Ancien Régime and of the writings of Christoph Martin Wieland, who they alleged was a corrupter of morals; all these themes were brought before the public in their mouthpiece, the Göttinger Musenalmanach. Although the Bund as such was already history by the time the young student from the Odenwald arrived in Göttingen, the temporary return of Hahn allowed his ideas a brief summer-long period of extra time.

For Kraus, at any rate, Hahn’s friendship seems to have had a liberating effect on his subsequent artistic output. So much is revealed by the anonymously published pamphlet Etwas von und über Musik fürs Jahr 1777 (Something of and about music for the year 1777), written within the space of a few months, in which Kraus permits himself to defy many a composing luminary of the day in eloquent and irreverent fashion. In the course of the essay’s interjections and exclamation marks, the lively objections and brief rejoinders by both named and unnamed interlocutors, one thing quickly becomes clear: what surges forth here is once again the voice of Sturm und Drang, the cult of genius that had become so fashionable. And yet one may ask whether the very clear partisanship on behalf of Gluck’s operatic reform programme that emerges so clearly here actually derives from genuine admiration of the Viennese dramatist rather than from a Hainbund-motivated rejection of Wieland’s libretto for Anton Schweitzer’s Alceste (1773). A few years later, when Kraus was fortunate enough to meet the grand seigneur of Classical music theatre in person, he drew a portrait of him that might have come straight from some heroic poem by Klopstock: «I have found my Gluck – he esteems me, that is good; but he also loves me, and that is better! He is a kind-hearted man, but fiery as the devil, and in that respect I am a mere jest compared to him. When he really puts his mind to it – oh my! Then he really roars, and every nerve is strained and vibrates.»1

In the meantime, other important events occurred in the young man’s life, the first of which was the decision he made in Göttingen to devote himself henceforth to music and to turn his back on his homeland. A more or less direct stimulus for this may have come from Carl Stridsberg, a friend and fellow student who was also a poet: he not only conceived a stage work with Kraus, but also painted an enticing picture of his Swedish homeland as a paradise of the fine arts.

The point of departure for the period of cultural prosperity that the Kingdom of Sweden experienced towards the end of the eighteenth century was the accession of its monarch Gustav III (of German blood on his mother’s side), who reigned from 1771 to 1792. Already in the first years of his reign he had founded two academies in Stockholm – one for music, the other for the fine arts – to the leading positions in which he appointed outstanding personalities from home and abroad. One of these was our Kraus, who had previously refused all protection and recommendation from those in high places, but was finally given an opera commission there a full two years after his arrival in Sweden, in June 1780: the libretto, called Proserpin, was written by the court poet Johan Henrik Kellgren.

From then on his situation quickly improved: before the end of the year Kraus was commissioned to rehearse Gluck’s Alceste and appointed a member of the Academy of Music. This is followed by the successful premiere of Proserpin at Ulriksdal Castle (1 June 1781) and, barely two weeks later, his appointment as deputy Kapellmästare at court.

Now the road to success seemed to lie open before Kraus. The Royal Opera House, which had been under construction since 1775, was due to be opened in Stockholm’s Gustav Adolfs torg (Square) at the beginning of 1782 with another stage work by the newly appointed deputy Kapellmästare – Aeneas i Carthago was its title. But the inauguration date was delayed and, even worse, when the composition was already more than half finished, a rueful Kraus was obliged to break to his parents the news that the prima donna Caroline Müller, cast in the role of Dido, had left Sweden to flee her creditors. This event brought to a premature end his biggest undertaking so far in the world of music theatre. Kraus’s king then sent him on an educational grand tour of the cultural centres of Europe within a week of the opening of the opera house, which finally took place on 30 September 1782 with a singspiel by Naumann. Contrary to appearances, however, the journey was not intended to make amends for Kraus’s disappointment, but in fact been had already planned for a long time.

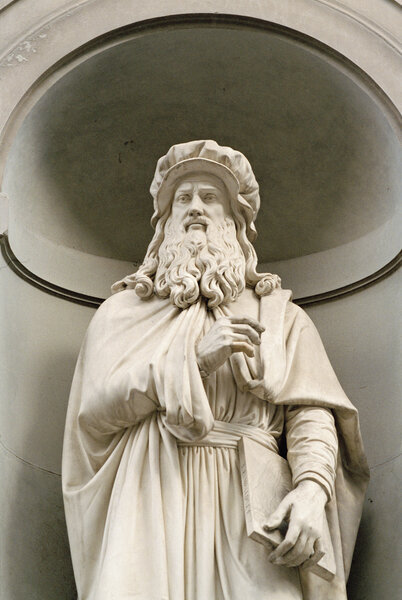

Berlin, Dresden, Vienna, Eszterháza, Venice, Florence, Rome, Naples and Paris, plus an excursion to see Padre Martini in Bologna and to the Handel centenary celebrations in London – the itinerary will hardly surprise anyone who is knows the importance of music theatre in the output of the German-Swedish composer. And yet it was above all his symphonies (more than a dozen of which may already have been in existence when he set off on his journey) that were decisive in spreading the fame of Kraus the «Classicist». It would appear that the young musician – who was well aware of his «genius» and more than once gave priority to «fullness of heart» (the concept of «Fülle des Herzens» dear to the Hainbündler Leopold zu Stolberg) over the prudence of the older generation – hardly ever sought to supplement his travel budget by selling any of the music he had brought with him.

Haydn was not the only one to be astonished by this attitude. His well-meant advice to bear in mind the importance of «ringing coin of the realm» earned the older composer a biting put-down in Kraus’s correspondence. In this respect, however, another acquaintance – the commercial agent Johann Samuel Liedemann – could rejoice in a gesture of quite another sort, which he mentioned in a letter to Emerich Horváth-Stansith de Gradec, scion of a Hungarian noble family and vice-ispán (viscount) of Spiš County: «All we have of him consists of an overture from his opera, a quartet from among his earlier works, and a sonata which he inscribed to me as a memento of his friendship. Now he is working on a symphony, which he will also dedicate to me.»2

We have now reached September 1783. Kraus had been staying in the capital of the Habsburg Empire since the beginning of April, attending opera and oratorio performances, giving private concerts in the house of his friend Liedemann and meeting the leading figures of the Viennese music scene. Christoph Willibald Gluck, to whom he was drawn like a «pilgrim to relics of the Holy Land»3, was top of the visiting list. This was followed by encounters with Salieri, Vanhal and Albrechtsberger (whom he found «good as gold») and an audience with Emperor Joseph II. There is no report of any meeting with Mozart, however, and the decision, shortly before he travelled on to Italy at King Gustav’s command, «to go to Eszterháza for a short time to take leave of my Haydn»4 seems to have brought about the first and only meeting of Kraus and Haydn, whose responsibility for the current theatrical season at Eszterháza Palace made his presence indispensable there and thus precluded a visit to Vienna.

But that meeting did not take place for another couple of weeks, during which the young Swede obviously tried to do something to further the dissemination of his musical œuvre. Hence he not only carried on composing, but also made contact with the copyist’s workshop of Johann Traeg, whose manuscript copies of music enjoyed widespread distribution beyond the borders of Austria. In this context, there are repeated references to a »Symphony in C minor«, a work which in the distant future was to be singled out from the small but extremely distinguished canon of symphonic works by Joseph Martin Kraus as one of »the most significant examples of its genre from the 1780s.«5

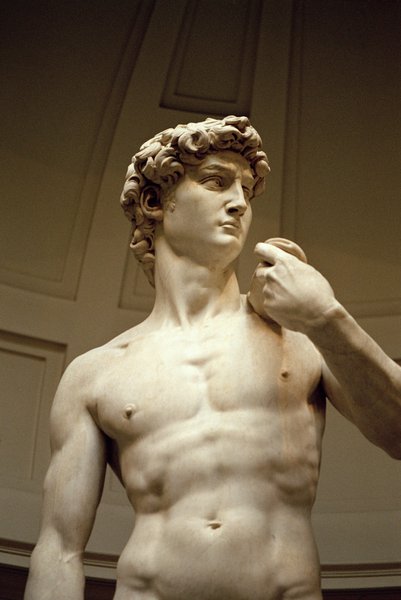

The true success story of the Symphony in C minor, which had probably been available in Traeg’s copies of the parts since the beginning of 1784, only really got underway when it was published by Breitkopf & Härtel in Leipzig in 1797, at the instigation of Fredrik Samuel and Gustav Abraham Silverstolpe. The fact that a laudatory review soon followed in the newly founded Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung seems to have been just as beneficial to the Silverstolpe brothers’ efforts as the words of Joseph Haydn, who is said to have remarked that same year to Fredrik Samuel, then serving as a diplomat in Vienna: »Kraus was the first man of genius I ever knew. Why did he have to die? He is an irreplaceable loss for our art.«6

The surviving autograph manuscript of the work probably dates from Kraus’s later stay in Paris and is a revision of the Sinfonia in C sharp minor VB 140, written earlier in Stockholm, now augmented by a second pair of horns and influenced by the impressions he had gained in Vienna. It begins with a slow introduction, which in turn pays homage to his »Ritter Gluck«, quoting the opening of the Overture to Iphigénie en Aulide in expanded scoring and with a more densely developed contrapuntal texture. The subsequent course of the composition, expressed in urgent musical discourse, has rarely been so tellingly described as by the eloquent pen of the music theorist and reviewer Justin Heinrich Knecht: »One must indeed admire the exquisite, soul-stirring modulations that pour forth one after another in this symphony, the splendid and distinctive bass lines, the assiduous handling of the inner voices, the beautiful and simple accompaniment of the wind instruments, and above all the impassioned ideas of this great master.«7

Even if – to return to Haydn – his enthusiasm for Kraus was probably kindled more by the Symphonie funèbre on the death of Gustav III, which Silverstolpe presented to him as a gift by in 1797, than by this musical monument to the younger man’s veneration of Gluck, we may infer from another quotation from a letter by Johann Samuel Liedemann dated December 1783, which refers to the meeting of the two composers at Eszterháza, that although »Kraus’s pieces... are not to his Prince’s taste, when the Prince is absent and he wants to spend a good day«, Haydn had those very pieces played to him.8

Thus Kraus must have continued his journey into Italian territory with a certain feeling of satisfaction, and not only because Prince Esterházy had shown himself »most condescending« towards him and he had been able to establish new friendships and business relations in Vienna. At any rate, his compositional output had grown considerably there – by about twenty songs, a string quartet, a flute quintet and at least one, if not several symphonies...

1 Letter from Kraus to his parents in Amorbach (Odenwald), dated »Wien den 28t Junius 1783«.

2 Ingrid Fuchs, »Haydniana in einer altösterreichischen Adelskorrespondenz«, in Internationales musikwissenschaftliches Symposium »Dokumentarische Grundlagen der Haydnforschung« im Rahmen der Internationalen Haydntage Eisenstadt, 13. und 14. September 2004, ed. Georg Feder & Walter Reicher (Tutzing: 2006), pp.55-79, here p.72.

3 Draft letter to the Stockholm theatre director Christoffer Bogislaus Zibeth, dated »[Vienna,] 15 [April 1783]«.

4 Cf. note 1 1.

5 Gabriela Krombach, article »Kraus, Joseph Martin«, Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Zweite, neubearbeitete Ausgabe, ed. Ludwig Finscher, Personenteil, vol. 10 »Kemp-Lert» (Kassel, Stuttgart etc.: 2003), columns 622-626, here column 624.

6 Letter from F. S. Silverstolpe to Marianne Lämmerhirt née Kraus, the composer's sister, published in Helmut Brosch, »Quellen zur Biographie von Joseph Martin Kraus, c) Frederik Samuel Silverstolpes Briefwechsel mit Kraus' Vater, Schwester und Schwager«, Mitteilungen der Internationalen Joseph-Martin-Kraus-Gesellschaft, vol. 5/6, 1986, pp.1-35, here p.21.

7 Justin Heinrich Knecht, »Recensionen. Oeuvre de Joseph Kraus, Maitre de Chapelle de S.M. Le Roi de Suede. Premier Cahier […] 1) Sinfonie für ein grosses Orchester [...]«, Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, vol. 1, 3 Oct. 1798 - 15 Sept. 1799 (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel), columns 9-11, here column 11.

8 Fuchs, op. cit., p.73..

to the shop

Joseph Haydn (1732–1809): Symphony No.19 in D Major, Hob. I:19 (ca. 1760/61)

Allegro molto / Andante / Finale. Presto

SYMPHONY NO.19 IN D MAJOR HOB. I:19 (c. 1760/61)

Time of creation: till 1766 [1760/1761]

Allegro molto / Andante / Finale. Presto

Christian Moritz-Bauer

«One day the old Prince Antonio Esterházy went to the house of Count [Morzin] to listen to music. He was a passionate music lover who had in his service a large and handpicked orchestra, directed by Maestro Werner. After hearing a symphony by Haydn (it was the one in D major and in three-four time), the Prince took a liking to the composer’s style and urged the Count to let him have the man. The Count, who had recently been thinking of dismissing his orchestra for financial reasons, was happy to comply with the Prince’s wishes.»1

What Giuseppe Carpani, one of the first biographers of Joseph Haydn, so eagerly reports here seems – despite minor historical inaccuracies – to reflect a quite conceivable scenario from our composer’s artistic career. For he is describing here the possibly decisive moment when a first hearing of Haydn’s music persuaded the then head of the Hungarian princely family of Esterházy to poach the almost thirty-year-old Kapellmeister from his former employment in a post alternating between Unter-Lukawitz near Pilsen2 and the Habsburg metropolis of Vienna.

We now know that Carpani’s text, whose truthfulness has often been called into question, is here verifiably close to reality. This has been shown by the chronological studies of the Haydn scholar Sonja Gerlach, according to which the composition assigned to no.19 in Eusebius Mandyszewski’s traditional numbering of Haydn’s symphonies is not only stylistically a transitional work between the early Morzin symphonies and the first ones he subsequently wrote for the Esterházy family, but also stands out as the only D major work in a group of three symphonies beginning with a 3/4 time signature, which, on stylistic grounds, could be dated to the time around Haydn’s first change of employer, that is, around the turn of the years 1760 and 1761.3

It has frequently been emphasised that one of the great merits of Hob. I:19, which does not seem particularly striking in terms of instrumentation and formal layout, is the ‘compositional unity’ of its opening Allegro molto. What is meant by this is that its structure, which the formal theory of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries labels with terms such as ‘exposition, ‘development’ and ‘recapitulation’, may be described not only as a mere stringing together of small musical components called ‘motifs’, but far more aptly – thanks to a complex system of mutual references among those components – as an overall trajectory divided into periodic sections by cadences. For all its inherent compositional learning, however, the first movement of this D major symphony also holds in store some striking moments that make one sit up and take notice, such as the wild tremolo passages accompanied by sudden tutti effects that even temporarily jolt the harmonic progression into the dark key of B minor at one point.

In several respects, though, the ensuing Andante is astonishing too: despite its brevity, it offers unusual rhythmic variety. There is, for example, the consistent use of anacrusis in the successive phrases of the melodic line, which, with its staccato quaver motion, takes on an almost march-like character, or the syncopated passage immediately following this, which seems positively redolentof the later Haydn, when the second violin – following the string bass at a distance of a semiquaver – suddenly turns out to be the leading voice. The tonal scheme of this central movement also leaves a lasting impression: most of it is in D minor, but it does not baulk at occasional excursions into G minor, F major and A major.

The work’s range of thematic references is rounded off by a Presto finale in a dancing 3/8 – a metre often encountered at the time, for example in the output of Georg Christoph Wagenseil – with catchy motifs reminiscent of hunting calls and ostinato-type galloping figures driven forward by the lower strings. Is the underlying message here an allusion by the composer to a certain ‘princely pleasure’ that was also very popular in the Esterházy family? Here, too, a prominent tremolo passage is extremely effective. Extending over several bars, in a descending sequence characterised by leaps of a sixth, an octave and even a tenth, it seems like a precursor to a certain ‘Sturm und Drang’ idiom that was to become such an enduring feature of Haydn’s compositional vocabulary in a few years’ time.

1 Giuseppe Carpani, Le Haydine, ovvero Lettere su la vita e le opere del celebre maestro Giuseppe Haydn (Milan: Buccinelli, 1812), p.87.

2 Now Dolní Lukavice (usually called Lukavec in English) near Plzeň in the Czech Republic. (Translator’s note)

3 Sonja Gerlach, «Joseph Haydns Sinfonien bis 1774. Studien zur Chronologie», in Haydn-Studien 7/1-2 (1996), pp.1-288, especially pp.71-75.

to the shop

Joseph Haydn (1732–1809): Symphony No.80 in d Minor, Hob. I:80 (1784)

Allegro spiritoso / Adagio / Menuet – Trio / Finale. Presto

SYMPHONY NO. 80 IN D MINOR HOB. I:80 (c. 1783/84)

Time of creation: [till 8.11.1784]

Allegro spiritoso / Adagio / Menuet – Trio / Finale. Presto

Christian Moritz-Bauer

A whole decade had passed since Haydn had composed his last major orchestral work in a minor key, the so-called »Farewell« Symphony. But during that time he had been anything but idle in the field of symphonic music and had enriched his musical language with many a new idiom. In discussing this period, specialists usually assert that Haydn (by and large) abandoned the extreme compositional style, traditionally described by the term »Sturm und Drang« (Storm and stress, borrowed from literary scholarship), which had come to the fore in a whole series of his works from the late 1760s onwards.

Nevertheless, it is now hardly tenable for anyone speaking from a well-informed perspective to state that Haydn’s symphonic œuvre subsequently became less »experimental« but markedly more »popular«. Nor can it be disputed that »musical Sturm und Drang« was a widely favoured stylistic device in its heyday.

The extreme, rugged, unbridled element in the composer’s vocabulary was henceforth relegated to the background, yet never entirely disappeared. One of the reasons for this is probably to be found in the fact that, after a new contract of employment dated 1779 allowed him actively to purvey his own musical creations to the international music market, Haydn made it a rule to round off each of his subsequent projects for publication with a work in the minor key. This decision was to have its impact, first of all, on the trilogy of symphonies Hob I:76-78, composed around 1782 and promoted shortly afterwards (by its composer) as ‘beautiful, resplendent and by no means over-long’, which features a work »ex C minore« in final position. And the following symphonic cycle includes the »Sinfonia in D la Sol re minore / Di me Giuseppe Haydn« – as it is designated in the autograph title of a set of parts sent as engraver’s copy for the London first edition, published by William Forster – that is discussed here.

The genuinely stormy beginning of Hob. I:80 has been variously described as »turbulent and unstable«,1 »serious« and »vehement«,2 and as a »violent complex, sombre in tone, but only sketchily outlined in thematic terms and harmonically restless«.3 And indeed the audience feels it has entered the symphony in medias res, on a »powerfully emphatic melody accompanied by flickering string tremolos«4 dominating the first bars that gives the impression that it has been shorn of its opening or torn from a broader context.

From a compositional standpoint, however, a three-note motif with a variable interval structure also clamours for mention in this context; it will have a decisive influence on the atmosphere of the first thematic period. The same motif then leads into a supposed »subsidiary theme«, which, however, is in its turn interrupted by a diminished seventh chord before it can form a proper closing cadence and, seemingly against its will, driven further on into F minor. Up to this point, as A. Peter Brown aptly observed, everything has been »almost one big Sturm und Drang gesture«.5 Then, however, something outrageously Haydnesque happens: following an appoggiatura figure suggesting a snap of the fingers, in waltzes a flute- and violin-led ländler theme with pizzicato accompaniment – and when, after another seven bars, the sign for skipping back to the start of the movement appears, one wonders what will come next, especially since (after the double bar following the expected exposition repeat) the ensuing formal section begins like a moment of reflection, with a two-bar general pause. What could have happened in the composer’s hothouse of ideas? By way of incisive seventh chords and many a harmonic terra incognita (initially D flat major!) the storm then sweeps along in G minor until the ländler once again stops it in its tracks and demands a switch to F major. When the string basses subsequently agree on a pedal point on A, the composer’s plan becomes crystal clear: the goal is D major, and the preceding battle of major and minor modes is finally over when the ‘subsidiary theme’ celebrates its triumphant return with the appropriate change of key signature.

The second movement of the symphony leads us into a related sphere that is nevertheless different again. It is an Adagio in B flat major, the subdominant of D minor. Although, in terms of key, this therefore establishes a relationship with the work’s sombre beginning, the mood now takes a cheerful and affable turn, open to the world and love. The conjecture that Haydn intended to forge a link with the opera house here, with his extravagant melodic arcs enriched with all manner of ornamentation, may well be found thoroughly convincing, since he had been working almost simultaneously on Armida, the last stage work he wrote for the theatre at Eszterháza Palace.

However that may be, the musical respiration is impressive in length and indeed runs right through all the sections of the classical sonata form, to which a subsidiary theme accompanied by sextolet arpeggios, a transition in dotted rhythms and a dance-like closing idea are added in the course of the exposition. It almost goes without saying that, in the midst of this idyll, there are bound to be momentary darkenings, diverse dramatic breaks and melodic standstills.

Reverting to the initial D minor, the symphony continues with the expected minuet, which opens by quoting the three-note motif of the Allegro spiritoso. A tense, energetic three-four time? Would the earlier ländler not have fitted in much better here? Haydn may well have had this hypothetical listener’s question in mind when he conceived his work. At any rate, the conflict between the modes seems to play a certain role here too, for after a few ambiguous bars the Trio section with its simplistic theme for unison oboe, horn and violin reverts decisively to the major.

By contrast, the beginning of the Presto finale, which Walter Lessing once described as »a masterstroke of bizarre humour and rhythmic delicacy, coupled with surprising instrumental and harmonic effects«,6 seems utterly »obscure«. How right Lessing was: to wait until almost the end of its twelve-bar introductory phase to »out&rlquo; a theme that appears to be in straightforward two-four time in all the string parts and reveal that it is in fact syncopated on the offbeat – that borders on temerity!

The syncopated motif quickly takes possession of the other orchestral parts, while the violins are able to gain a brief breathing space for a few bars with impetuous semiquavers. Of course the fugitives are immediately recaptured and watched with eagle eye by a chromatic motif surrounding them in all the other parts – until they break free again and throw the gates open to a modest but finely made melody in thirds on the oboes. Lively rising staccato motifs lead into the exposition repeat and then into the second half of the movement, which, in Ludwig Finscher’s view, is a »real tour de force of [motivic and] thematic working«.7 With its accentuated chromaticism and its combination of syncopated and staccato motifs, the conclusion of the last movement proves to be as eventful as it is adventurous in its harmonic forays, which range from D minor or F major, through G minor, F sharp minor and C sharp minor, all the way to B major and ultimately D major – an extraordinary ending to an extraordinary symphony!

1 Matthew Riley, The Viennese Minor-Key Symphony in the Age of Haydn and Mozart (Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), p. 210.

2 Andreas Friesenhagen, booklet note to the CD ‘Haydn. The Harmonia Mundi Edition: Violin Concerto no.1, Symphonies no.49 »La Passione« & no.80. Freiburger Barockorchester, Gottfried von der Goltz’ (Arles: Harmonia Mundi, HMX 2962029, 2009), p.13..

3 Ludwig Finscher: Joseph Haydn und seine Zeit. Laaber 2000, p. 318.

4 Friesenhagen, ibid.

5 A. Peter Brown, The Symphonic Repertoire Vol. II – The First Golden Age of the Viennese Symphony: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002), p.203.

6 Walter Lessing, Die Sinfonien von Joseph Haydn, dazu: sämtliche Messen, vol. II (Baden-Baden: Südwestfunk,1988), p.233.

7 Finscher, op. cit., p.318 f.

to the shop

Line-up

Basel Chamber Orchestra

Giovanni Antonini, conductor

- Line-up orchestra

1st violin Yuki Kasai, Valentina Giusti, Ewa Miribung, Elisabeth Kohler, Irmgard Zavelberg, Tamás Vásárhelyi

2nd violin Anna Faber, Matthias Müller, Fanny Tschanz, Regula Keller, Mirjam Steymans-Brenner

Viola Mariana Doughty, Bodo Friedrich, Renée Straub, Anna Pfister

Cello Christoph Dangel, Georg Dettweiler, Hristo Kouzmanov

Bass Stefan Preyer, Daniel Szomor

Flute Isabelle Schnöller

Horn Konstantin Timokhine, Mark Gebhart, Lars Magnus, Andreas Kamber

Oboe Emiliano Rodolfi, Thomas Meraner

Bassoon Carles Cristobal Ferran, Letizia Viola

Biographies

Orchestra

Basel Chamber Orchestra

Orchestra

The Basel Chamber Orchestra is deeply rooted in the city of Basel - with its two subscription series in the Stadtcasino Basel as well as its own rehearsal and performance venue, Don Bosco Basel. With world tours and more than 60 concerts per season, the Basel Chamber Orchestra is a popular guest at international festivals and in Europe’s most important concert halls.

As the first orchestra to be awarded the Swiss Music Prize in 2019, the Basel Chamber Orchestra stands out for its excellence and diversity as well as for its depth and consistency. Its interpretations are deeply immersed into the relevant thematic and compositional worlds: in the past with the "Basel Beethoven" or with Heinz Holliger and our "Schubert Cycle". Or as with the long-term project Haydn2032, the study and performance of all Joseph Haydn's symphonies up to the year 2032 under the direction of principal guest conductor Giovanni Antonini and together with the Ensemble Il Giardino Armonico. From the current season onwards, the Basel Chamber Orchestra has decided to devote itself to all the symphonies of Felix Mendelssohn under the direction of the early music specialist Philippe Herreweghe.

The Basel Chamber Orchestra frequently collaborates with selected soloists such as Maria João Pires, Jan Lisiecki, Isabelle Faust and Christian Gerhaher. The Basel Chamber Orchestra presents its broad repertoire under the artistic direction of the first violins and the baton of selected conductors such as Heinz Holliger, René Jacobs and Pierre Bleuse.

The concert programmes are as diverse as the 47 musicians and range from early music on historical instruments to contemporary music and historically informed interpretations.

An important element of the work is the future-oriented education programs in large-scale participatory projects involving creative exchange with children and young people.

The creative work of the Basel Chamber Orchestra is documented by an extensive and award-winning discography.

The Clariant Foundation has been the presenting sponsor of the Basel Chamber Orchestra since 2019.

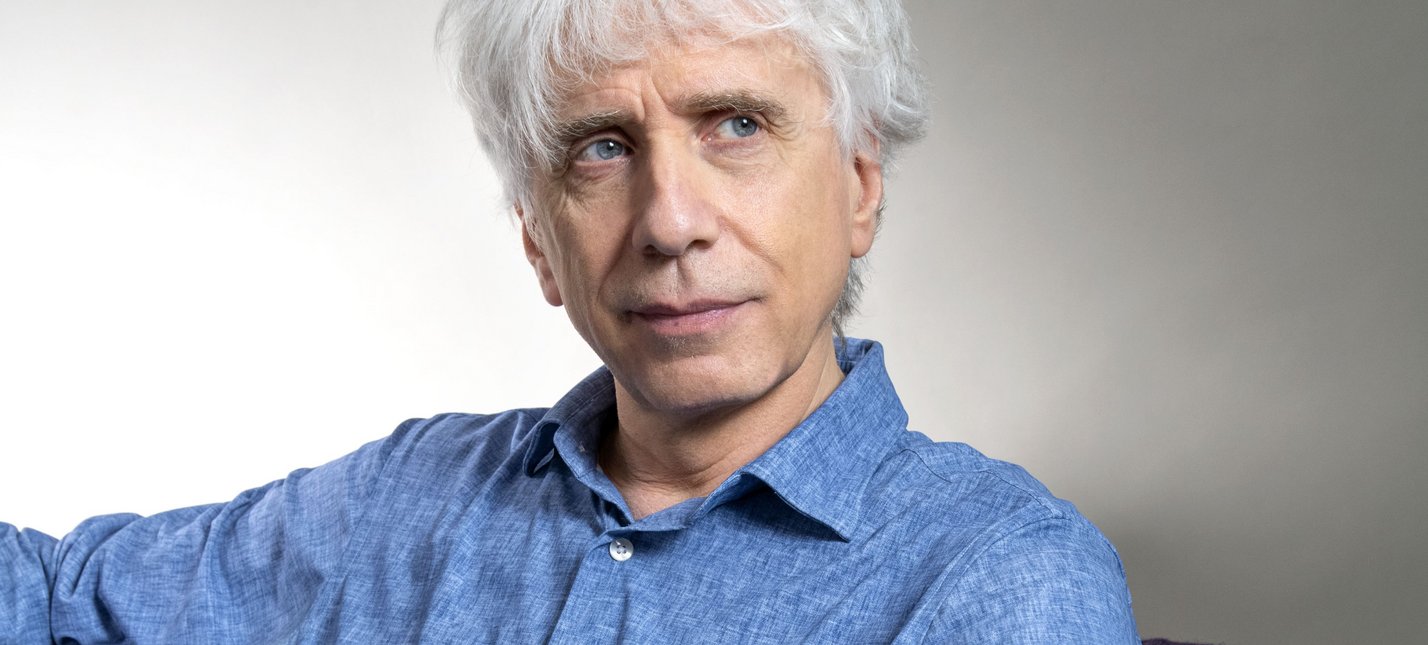

Conductor

Giovanni Antonini

Conductor

Born in Milan, Giovanni studied at the Civica Scuola di Musica and at the Centre de Musique Ancienne in Geneva. He is a founder member of the Baroque ensemble “Il Giardino Armonico”, which he has led since 1989. With this ensemble, he has appeared as conductor and soloist on the recorder and Baroque transverse flute in Europe, United States, Canada, South America, Australia, Japan and Malaysia. He is Artistic Director of Wratislavia Cantans Festival in Poland and Principal Guest Conductor of Mozarteum Orchester and Kammerorchester Basel.

He has performed with many prestigious artists including Cecilia Bartoli, Kristian Bezuidenhout, Giuliano Carmignola, Isabelle Faust, Sol Gabetta, Sumi Jo, Viktoria Mullova, Katia and Marielle Labèque, Emmanuel Pahud and Giovanni Sollima. Renowned for his refined and innovative interpretation of the classical and baroque repertoire, Antonini is also a regular guest with Berliner Philharmoniker, Concertgebouworkest, Tonhalle Orchester, Mozarteum Orchester, Leipzig Gewandhausorchester, London Symphony Orchestra and Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

His opera productions have included Handel’s Giulio Cesare and Bellini’s Norma with Cecilia Bartoli at Salzburg Festival. In 2018 he conducted Orlando at Theater an der Wien and returned to Opernhaus Zurich for Idomeneo. In the 21/22 season he will guest conduct the Konzerthaus Orchester Berlin, Stavanger Symphony, Anima Eterna Bruges and the Symphonieorchester de Bayerischer Rundfunks. He will also direct Cavalieri’s opera Rappresentatione di Anima, et di Corpo for Theatre an der Wien and a ballet production of Haydn’s Die Jahreszeiten for Wiener Staatsballett with the Wiener Philharmoniker.

With Il Giardino Armonico, Giovanni has recorded numerous CDs of instrumental works by Vivaldi, J.S. Bach (Brandenburg Concertos), Biber and Locke for Teldec. With Naïve he recorded Vivaldi’s opera Ottone in Villa, and, with Il Giardino Armonico for Decca, has recorded Alleluia with Julia Lezhneva and La morte della Ragione, collections of sixteenth and seventeenth century instrumental music. With Kammerorchester Basel he has recorded the complete Beethoven Symphonies for Sony Classical and a disc of flute concertos with Emmanuel Pahud entitled Revolution for Warner Classics. In 2013 he conducted a recording of Bellini’s Norma for Decca in collaboration with Orchestra La Scintilla.

Antonini is artistic director of the Haydn 2032 project, created to realise a vision to record and perform with Il Giardino Armonico and Kammerorchester Basel, the complete symphonies of Joseph Haydn by the 300th anniversary of the composer’s birth. The first 12 volumes have been released on the Alpha Classics label with two further volumes planned for release every year.

Videos

Recordings

VOL. 5 _L'HOMME DE GÉNIE

CD

Giovanni Antonini, Basel Chamber Orchestra

Symphonies No.19, No.80, No.81

J. M. Kraus: Sinfonie in C-Major, VB 142

Available at:

Bider&Tanner, Basel

Outhere Music

Download / Stream

VOL. 5 _L'HOMME DE GÉNIE

Vinyl-LP with book (download code CD included)

Giovanni Antonini, Basel Chamber Orchestra

Symphonies No.19, No.80, No.81

J. M. Kraus: Sinfonie in C-Major, VB 142

Essay "Joining a String Quartet at 12. Why I Married a Psychiatrist." by Eva Gesine Baur

Available at:

Bider&Tanner, Basel

Joseph Haydn Stiftung, Basel

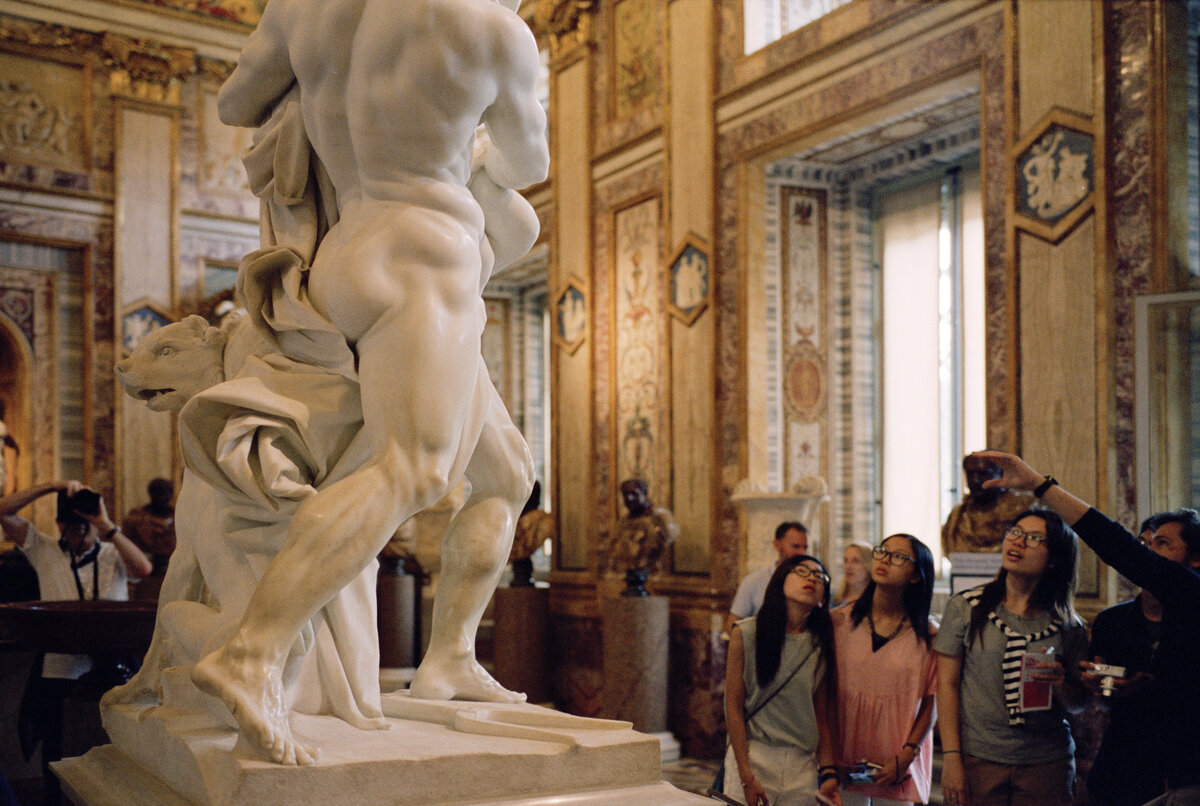

© Stuart Franklin / Magnum Photos

Biography

Photographer, Magnum Photos

Stuart Franklin

Photographer, Magnum Photos

Stuart Franklin was born in Britain in 1956. He studied photography and film at West Surrey College of Art and Design and geography at the University of Oxford (BA and PhD). During the 1980s, he worked as a correspondent for Sygma Agence Presse in Paris before joining Magnum Photos in 1985.

Franklin was the elected President of Magnum Photos from 2006-2009.

Franklin is best known for his celebrated photograph of a man defying a tank in Tiananmen Square, China, in 1989, which won him a World Press Photo Award. Since 2004 he has focused on long-term projects concerned primarily with man and the environment.

At twelve I wanted to be all sorts of things. Except for the one thing I actually was at twelve: an outsider.

It happened very quickly. I just turned down an invitation to a party.

You got something better to do, or what?

I’m going to a concert.

Mireille Matthieu? Dalilah Lavi? Simon & Garfunkel? Vicky Leandros? The Rollings Stones? Reinhard Mey?

No, the "Amadeus" Quartet.

Don’t know ’em. They like ABBA?

No, it’s a string quartet.

A what?

Two violinists, a viola player and a cellist.

Are you taking the piss?

Everyone found out.

Up until that point I was form prefect. Never again.

I’d always thought that classical music was something that no one was that bothered about.

Excerpt from the essay "Joining a String Quartet at 12. Why I Married a Psychiatrist." by Eva Gesine Baur

The essay "Joining a String Quartet at 12. Why I Married a Psychiatrist." by Eva Gesine Baur was published in the vinyl edition vol. 5.

Biography

Writer

Eva Gesine Baur

Writer

Award-winning Eva Gesine Baur is a renowned expert in Cultural History with degrees in Literature, History of Art and Musicology. For a long time she worked as journalist, specialising in artist portraits, special features and essays. She is currently based in Munich, where she works as non-fiction author, publicist and freelance writer. She writes biographies (such as Mein Geschöpf sollst du sein. Das Leben der Charlotte Schiller; Chopin oder die Sehnsucht; Emanuel Schikaneder; and Mozart. Genius und Eros) as well as literary travel guides (including Schauplatz Salzburg; Freuds Wien; Amor in Venedig). Eva Gesine Baur also writes novels under the pseudonym Lea Singer with publications (such as Die Zunge. Wahnsinns Liebe; Mandelkern; Konzert für die linke Hand; Der Opernheld; Verdis letzte Versuchung; Poesie der Wolken). In 2009, Gesinge Baur held the coveted Poetics Lectureship in Padeborn. In 2010m she was awarded the Hannelore Greve Prize by the Hamburger Autorenvereinigung in Hamburg for her fiction works and in 2016 she received the Großen Schwabinger Kunstpreis in Munich for her lifetime work.