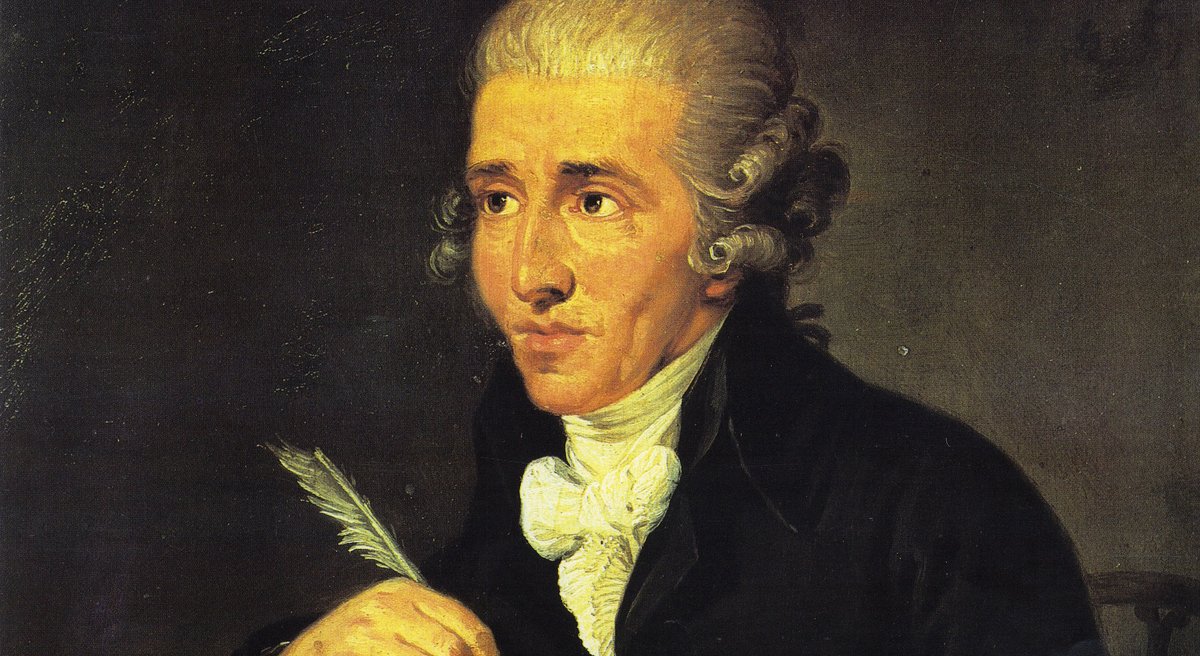

About Joseph Haydn

Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) is regarded as the founder of ‘Viennese Classicism’, even though he spent many years of his life in Hungary and enjoyed his greatest triumphs in London. He created a revolutionary language in which instrumental music achieved equal stature to vocal, thanks to its expressiveness and keenly intelligent wit: his sonatas, quartets and symphonies were literally snatched from his hands by publishers all over Europe. Haydn, the modest son of a cartwright, continued to say throughout his life that his example showed how ‘something can come of nothing’. And often in his compositions, too, a miraculous musical discourse develops from an inconspicuous motif.

-

Childhood and adolescence (1732–1749)

Franz Joseph Haydn was born on 31 March 1732 in the little village of Rohrau in Lower Austria near the Hungarian border, the son of a wainwright called Matthias and his wife Anna Maria. Joseph was the second of their twelve children; their sixth child was Johann Michael (1737–1806), who was also to become a composer. The young Haydn’s first experience of music was at home; his father enjoyed music-making, and was ‘by nature a great lover of music’. When he was only about five, Joseph was sent to live in Hainburg with a distant relative called Johann Matthias Franck, from whom the boy received his first musical education.

Georg Reutter the Younger (1708–1772), who had succeeded his father as Kapellmeister at St Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna in 1738, was on the look-out for talented young choristers when he visited the parish priest in Hainburg, probably in 1739. He invited the young Haydn to sing for him, and recognised his gift for music. Joseph joined the choir school at St Stephen’s as a choirboy at the age of eight. As well as receiving a very ‘deficient education’ in general subjects, the boy was taught how to sing, and learned to play the harpsichord and violin.

The house of Kapellmeister Reutter, which was home to Haydn and another five choirboys, was located in the immediate vicinity of St Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna, nestling between a four-storey block of rented apartments and the chapel of St Mary Magdalene. Vienna, capital of the mighty Habsburg Empire, had been at the centre of an important musical tradition for generations: music enjoyed a golden age at the court of Emperor Charles VI due to the influence of the two leading representatives of the late Baroque period, Johann Joseph Fux (1660-1741) and Antonio Caldara (1670-1736). Haydn’s time as a choirboy came to an end in 1749/50 when his voice broke and he was dismissed from the choir school for alleged misbehaviour.

-

Apprenticeship and first appointment (1750–1761)

When Joseph Haydn was ejected from the choir school, he found himself without either an income or a roof over his head. In 1751, he took up residence in a wretched unheated garret in what was known as the Michaelerhaus, which can still be seen today near St Michael’s Church opposite the Hofburg Palace. During the next few years, Haydn’s principal source of income came from providing music lessons and working as an accompanist. For 60 gulden a year, he played for the Brothers of Mercy in Leopoldstadt, accompanying the 8 am Mass every Sunday and Friday. At 10 am he played in Count Haugwitz’s Chapel, and at 11 am sang Mass at St Stephen’s for the sum of 17 kreuzers.

Among the other residents of the Michaelerhaus were two individuals who were to play a significant part in the young man’s artistic career: the court poet Pietro Metastasio (1698–1782), who taught Haydn Italian, and the opera composer and singing teacher Nicola Antonio Porpora (1686-1768). Haydn was allowed to accompany Porpora’s pupils on the keyboard, and also served occasionally as his valet. He acknowledged to his biographer Griesinger that ‘at Porpora’s he benefited a great deal in singing, composition, and the Italian language’. On the first floor of the Michaelerhaus lived the widowed Princess Maria Octavia Esterházy (1683-1762), the mother of Princes Paul Anton and Nicolaus, who were later to employ Haydn as Kapellmeister.

Haydn wrote his first string quartets for Baron Karl Joseph von Fürnberg, and these quickly gained popularity. They were the first of his works to be printed abroad (Paris, 1764) – albeit without the composer’s knowledge. Haydn’s excursions to Baron Fürnberg’s castle at Weinzierl and his early string quartets were the prelude to his appointment as director of music to Count Morzin. In 1757, he was appointed Morzin Kapellmeister for an annual salary of 200 gulden plus bed and board, probably by Karl Joseph Franz (1717–1783/84?), son of the reigning Count Ferdinand Maximilian Franz (1693–1763). Among the compositions which Haydn wrote for the Counts Morzin are his first symphony and a number of divertimenti for wind instruments, usually pairs of oboes, horns and bassoons.

On 26 November 1760, Haydn married Maria Anna Aloysia Keller (1729–1800), the eldest daughter of a Viennese wig-maker. Haydn is believed to have fallen in love with the youngest daughter Therese first, but she entered a convent. His wedding to Maria Anna was celebrated at St Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna. Haydn’s was not a happy marriage: ‘My wife was unable to bear children, and therefore I was not indifferent to the charms of other women’, was one of the few comments he made about his married life. His biographers Griesinger and Dies had nothing good to report of Frau Haydn: according to them, she was uneducated, failed to recognise the genius of her husband, and was a spendthrift.

-

The early Esterházy period (1761–1775)

When the Morzin family got into financial difficulties and was compelled to dismiss its musicians, Haydn soon found a new employer in Prince Esterházy.

In 1761, when he took up his post, the permanent residence of the Esterházy princes was in the small Baroque town of Eisenstadt on the western shore of Lake Neusiedl. Haydn initially rented an apartment before buying his own house near the Franciscan monastery in 1766.

His new employer was Prince Paul I Anton Esterházy (1711–1762), who had inherited a love of music from his forefathers. The Esterházy family was one of the richest and most powerful in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. As well as several palaces in Vienna, it owned castles throughout Hungary and in what is now the Austrian province of Burgenland. The Esterházys lived a life of luxury, and reigned over their principality like sovereigns. An important period in Haydn’s life began in Eisenstadt: ‘...that is where I wish to live and die’, he wrote in a letter dated 6 July 1776. The first works he composed in his new post included the so-called ‘Time of Day’ symphonies, ‘Le Matin’, ‘Le Midi’ and ‘Le Soir’ (Hob. I:6-8), which were to be followed by twenty more symphonies between then and 1766.

Haydn signed a contract of employment with Prince Paul I Anton Esterházy on 1 May 1761. When he began working in Eisenstadt, he was originally appointed ‘vice-Kapellmeister’, as the elderly and infirm Georg Joseph Werner (1693-1766) was still officially the Prince’s director of music. Haydn’s contract obliged him to dress and conduct himself appropriately, set an example to his subordinate musicians, and compose music at the behest of the Prince. His duties ranged from maintaining instruments and cataloguing musical scores to teaching, composing and performing. Prince Paul I Anton Esterházy, who had a greenhouse in the palace grounds converted into a theatre, died on 18 March 1762.

Prince Nicolaus Esterházy (1714–1790) succeeded his brother Paul Anton on 17 May 1762. He was to be Haydn’s benefactor and employer for nigh on thirty years. He earned his epithet ‘der Prachtliebende’ (literally ‘lover of splendour’, but usually rendered as ‘the Magnificent’ in English) because of his predilection for spending large sums of money on extravagant entertainment and special celebrations: the poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe referred to the ‘Esterházy fairy kingdom’ in his first volume of memoirs in 1811. In many respects, Nicolaus I was an exemplary patron. Under his employ, Haydn rose to become the third-highest remunerated official in the Prince’s household. Referring to the great level of esteem he enjoyed under Nicolaus I, Haydn later recounted: ‘My Prince was content with all my endeavours; I received applause (...) I was cut off from the world (...) and so I was compelled to become original’ (Griesinger).

The Prince’s favourite instrument, which he had also learned to play, was the baryton, an instrument with similarities to the viola da gamba and the cello, which could not only be played with a bow, but also had strings behind the fingerboard which were plucked. Among Haydn’s compositions were 125 divertimenti for baryton, viola and cello, as well as numerous duos and pieces of ensemble music which included solos to be performed by the Prince. Following the death of Kapellmeister Georg Joseph Werner in 1766, Haydn assumed sole responsibility for music at the court.

Once he had been appointed principal Kapellmeister, he purchased a small house near the Franciscan monastery in Eisenstadt for 1,000 gulden. The house was to burn down twice, but on each occasion Prince Nicolaus had it rebuilt at his own expense, giving further proof of the esteem in which he held his Kapellmeister. For his part, Haydn swore that he would serve the Prince ‘until such time as the death of one or other of them determined otherwise’ (Dies). Haydn sold the house in 1778. Since 1935, it has been the home of the Haydn Museum.

Eszterháza (1766–1775)

The Esterházy princes owned a little hunting lodge near the south-eastern shore of Lake Neusiedl, which was named after the nearby town of Süttör. Prince Nicolaus I was particularly fond of this location, and decided to convert the building into a sumptuous summer residence, later to be known as ‘Eszterháza’. Erecting a ‘Hungarian Versailles’ at the marshy corner of a lake, which was to include an opera house, a puppet theatre and numerous ancillary buildings, and raising its status to that of a cultural centre on a par with the best in Europe, was undoubtedly one of the greatest achievements of this high-ranking family of western Hungarian magnates.From 1766/67, Eszterháza became the centre of Haydn’s working life; at first only in the summer months, but eventually for most of the year.

Haydn’s first opera written for the Esterházy court, Acide, was performed in Eisenstadt in 1763 on the occasion of the wedding of Prince Nicolaus’s eldest son, and La canterina (1766) was given in the same venue. After the court moved to Eszterháza, Haydn again turned to opera with Lo speziale (1768) and Le pescatrici (1770), but also to spoken drama, which was staged there annually by specially engaged theatre companies. Of particular importance for the production of Haydn’s own stage works – whether they belonged to the genre of opera, like L’incontro improvviso, or to that of incidental music for plays, such as the scores he wrote for Die Jagdlust Heinrich des Vierten (Collé) and Der Zerstreute (Regnard) – were the great court festivals of 1772, 1773 and 1775. Among these, the visit of Maria Theresia in September 1773 assumed special prominence, for the Empress had the opportunity to hear two new Haydn works for the stage: L’infedeltà delusa, a burletta per musica, and Philemon und Baucis, a puppet opera.

Haydn’s increasing orientation towards the theatre, which can be documented for the years from 1766 onwards, also had a stylistic effect on other areas of his compositional output, especially that of the symphony. A series of ‘entertainment symphonies’ (1765-1768) was followed by the composer’s so-called ‘Sturm und Drang’ period (1768-1772), which in turn merged seamlessly into a few years when his symphonies had a broadly theatrical quality (from 1773). In addition, Haydn reworked several scores of incidental music written during these years into concert symphonies, whether immediately or somewhat later (including nos. 28, 65, 60 and 67).

-

The middle Esterházy period (1776–1790)

Eszterháza II (1776–1784)

From 1776 onwards, opera and theatre productions became part of the Prince’s everyday life: during the period from 1780 to 1790 alone, Haydn directed more than 1,000 opera performances. Of the total of seventy-eight operas performed up to 1784, six were by Haydn himself, namely Il mondo della luna (1777), L’isola disabitata and La vera costanza (1779), La fedeltà premiata (1781), Orlando paladino (1782) and Armida (1784). This substantial work in the opera house placed an enormous strain on Haydn.On 14 May 1780, Haydn was awarded his first major foreign distinction: the Accademia Reale Filarmonica of Modena named him an honorary member. In Vienna in December 1781, he gave music lessons to Maria Feodorovna of Russia, the wife of the Grand Duke and later Tsar Paul I. Some of his earlier string quartets, later to become famous as op.33, are dedicated to the Grand Duke and are known as the ‘Russian’ Quartets.

Encouraged by his noticeably growing international reputation, Haydn began to aim his compositions primarily at a public audience and to focus increasingly on the needs of the market for printed music (the elimination of the princely exclusivity clause in his contract of service, renewed in 1779, provided the legal basis for this). In the field of the symphony, for example, two sets each consisting of three works were produced with a view to publication, whose filiation is indicated by aspects of the choice of key and mode: nos. 76, 77 and 78 of 1782 and nos. 80, 81 and 79 of 1784. Haydn’s relations with England also began to intensify after the first attempts were made to invite him to London in 1782.

In 1784 the building works at Eszterháza, which had been going on for over twenty years, were declared finished. The decline in the court festivities organised by Prince Nicolaus I, which had once been celebrated with such splendour, also had an impact on the compositional work of his Kapellmeister: on 26 February 1784, Haydn’s last opera composed for Eszterháza, Armida, had its premiere.

Eszterháza III (1785-1790)

As Haydn’s employer spent the last years of his life at Eszterháza in increasing seclusion, the composer tried to get away from the place at every possible opportunity – even if there were not many of these, owing to his still extremely time-consuming principal occupation as operatic impresario. For example, the Masonic movement, which gained popularity in educated circles during the reign of Emperor Joseph II (1780-1790), had aroused Haydn’s interest. This led to his being admitted to the Viennese Lodge ‘Zur wahren Eintracht’ (True Concord) on 11 February 1785. On the very next day, a private concert was held at the apartment of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791), at which string quartets composed by this native of Salzburg and dedicated to Joseph Haydn were performed. Leopold Mozart wrote the following famous words to his daughter about this concert: ‘[...] Herr Haydn said to me: Before God and as an honest man I tell you that your son is the greatest composer known to me either in person or by name; he has taste, and, furthermore, the most profound knowledge of composition.’An additional boost to his career was provided by important composition commissions that reached Haydn from a number of European countries. For instance, a commission for the orchestral workDie sieben letzten Worte unseres Erlösers am Kreuze

(The Seven Last Words of Our Saviour on the Cross) came from Cádiz in Spain. Haydn’s works also circulated widely in France. The ‘Paris’ Symphonies (nos. 82-87) and Symphonies nos. 88-92 owe their very existence to Claude-François-Marie Rigoley, Comte d’Ogny (1757–1790), one of the driving forces behind the ‘Concert de la Loge Olympique’ and a leading figure in French Freemasonry.

In June 1789, Haydn received a letter which was to form the basis for a friendship quite unlike any other. Marianne von Genzinger (1750–1793), the wife of Prince Nicolaus’s personal physician in Vienna, sent him a piano score which she had based on the Andante from one of his symphonies. Her request for corrections and the hope she expressed that she would soon see Haydn in Vienna was the prelude to a long correspondence which provides us with an insight into the composer’s personality. The admiration expressed by Frau von Genzinger, who was eighteen years his junior and a woman of remarkable refinement, prompted Haydn to divulge his innermost feelings to her and, in particular, to speak of the sense of isolation he felt in Eszterháza.

On 28 September 1790, Prince Nicolaus I, ‘the Magnificent’, breathed his last. His death marked the end of an era in the history of music. Prince Paul Anton II (1738–1794), the son and heir of Nicolaus I, did not share his father’s interest in music to anything like the same degree, and dismissed the orchestra and choir within a matter of days. Only Haydn and the Konzertmeister Luigi Tomasini remained officially in the service of the Prince. Haydn retained his title of Kapellmeister and an annual pension of 1,000 gulden, although he no longer had any duties to perform for Prince Paul Anton.

-

Journeys to England (1791–1795)

‘I am Salomon from London and have come to fetch you. Tomorrow we shall make an accord.’ That is how Haydn described to his biographer Alber Christoph Dies the decisive moment which was to result in him travelling to England. In return for the considerable sum of 5,000 gulden, he undertook to write an Italian opera, six new symphonies and a series of other compositions, and to perform them at concerts which he himself would conduct. Johann Peter Salomon (1745–1815), a famous violinist from Bonn who was also a successful concert promoter, wasted no time in informing the British public about Haydn’s imminent arrival. Haydn responded to Mozart’s objection that he could not even speak English with the reply, ‘My language is understood all over the world!’ (Dies).

On 1 January 1791, Haydn set foot on English soil after an arduous journey via Munich, Öttingen-Wallerstein, Bonn and Calais. Seven days later, he wrote to Marianne von Genzinger: ‘...my arrival caused a great sensation throughout the entire city, and for three successive days I was mentioned in all of the newspapers; everyone is eager to know me’. Another sensation was caused when, at a royal court ball in St James’s Palace, Haydn was greeted by the Prince of Wales with a noticeable bow. The first of the concerts organised by Salomon in the Hanover Square Rooms was held on 11 March 1791, and they continued every week until 3 June. These were extremely select society events, and entry was restricted to the aristocracy and the upper middle classes.

In late May 1791, Haydn attended the Handel Festival in Westminster Abbey, which was held every year under the patronage of the king. No other experience on English soil left such a lasting impression on the composer as this grand-scale commemoration. This was his first encounter with the oratorios Israel in Egypt, Esther, Saul and – the highpoint of the festival – Messiah.

At the close of his first successful London season, Haydn was awarded an honorary doctorate of music by the University of Oxford in July 1791, on the recommendation of the music historian Charles Burney (1726–1814). The grand ceremony was held in the city’s Sheldonian Theatre, and extended over three days. It was on this occasion that Symphony no.92, actually written earlier for performance in Paris, is reported to have been played; it later entered the annals of musical history as the ‘Oxford’ Symphony.

Until the beginning of the next concert season, Haydn withdrew from public life and gave private music lessons to Rebecca Schroeter (1751–1826) a member of a prosperous Scottish family and the widow of the German composer and keyboard player Johann Samuel Schroeter (who had died in 1788). A very close relationship developed between Haydn and his pupil. Her letters, which Haydn transcribed into his notebook, document the passionate feelings harboured by the forty-year-old for the nearly sixty-year-old composer: ‘…no language can express half the love and affection I feel for you’. Haydn was often Mrs Schroeter’s guest, and she took every possible care of the maestro’s mental and physical wellbeing. During his second visit to London, Haydn was a close neighbour of Rebecca Schroeter, and later dedicated his Piano Trios op.73 to her as a token of his affection.

Back in August 1791, Prince Paul Anton II Esterházy had expressed the wish that Haydn should, after all, return to Eisenstadt. However, the composer had certain contractual obligations to fulfil before he could do so, and it was not until late June 1792 that he left the British Isles at the end of another successful concert series. He stopped off in Bonn, where he made the acquaintance of the young Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827), before returning to Vienna. There it was agreed that Beethoven would visit Haydn in Vienna to study composition and counterpoint with him.

In January 1794, Haydn travelled to London for the second time with his private secretary and valet Johann Elssler (1769–1843). Salomon’s concert series, now renamed ‘the Opera Concert’, was once again very well received; it included the premiere of the ‘Military’ Symphony, which was to prove the most popular of Haydn’s orchestral works during his lifetime. During this visit, Haydn also established further contacts with a number of English publishers.

The list of works composed by Haydn for his two visits to England eventually numbered some 250 compositions, including the opera L’anima del filosofo, ossia Orfeo ed Euridice (The Soul of the Philosopher, or Orpheus and Eurydice), which was not performed at the time, the twelve ‘London’ Symphonies, six string quartets, thirteen piano trios, three piano sonatas and more than two hundred songs.

On 1 February 1795, Haydn was accorded the considerable honour of being the first living composer to be included in the programmes of the ‘Ancient Concerts’. He now found official admission to the concerts of King George III (1738–1820), to whom he was introduced on this occasion by George Augustus Frederick, Prince of Wales (1762–1830). In the spring of 1795, Haydn played, conducted and sang for the royal family a number of times, as well as performing at concerts held at Carlton House by the Prince of Wales (from 1820 King George IV). George III and his consort Queen Charlotte attempted to persuade Haydn to remain in England for longer, even offering him an apartment in Windsor Castle.

-

The late Esterházy period and Haydn’s death (1795–1809)

Paul Anton II died only a few days after Haydn’s departure from London in January 1794. His successor, Prince Nicolaus II (1765–1833), had informed the composer in the previous summer that he intended to reconstitute his orchestra, and as he continued to regard Haydn as his Kapellmeister, he was recalling him to Eisenstadt. Haydn was not unhappy to hear this news, as it meant he could be certain of his pension and of provision for his general welfare. In early September 1795, Haydn – now a world-famous, prosperous man – arrived in Vienna to serve what was now his fourth Esterházy prince, whose alterations to the palace and park in Eisenstadt have remained unchanged to this day.

Nicolaus II was passionate about the theatre and was a great art collector. However, his interest in music was restricted mainly to church music, so it became Haydn’s principal responsibility to compose masses. From 1795, he spent almost all of the remainder of his life in Gumpendorf near Vienna, apart from spending the summers in Eisenstadt, where, every September until 1802, he composed a mass for the name day of Princess Maria Josepha Hermenegild (1768–1845), which he then conducted in the Bergkirche. That this was the golden age of Haydn’s choral music is just as apparent from these masses as from his late oratorios.‘I was never as devout as when I was at work on The Creation; I fell to my knees daily’, Haydn confessed to his biographer Griesinger. After the monumental Handel performances Haydn had attended in London, it was his fervent wish to write an oratorio which would be a morally uplifting and artistic experience for its audience. The former diplomat and avowed music-lover Gottfried van Swieten (1730–1803) supplied the German libretto for the work, based on an English original of uncertain provenance. The premiere of Die Schöpfung (The Creation) took place on 30 April 1798 at the Palais Schwarzenberg on the Neuer Markt in Vienna before a select audience, and was a resounding success.

After he completed the follow-up work Die Jahreszeiten (The Seasons) and abandoned his work on the set of string quartets op.77, which had been commissioned by Prince Lobkowitz at the same time as Beethoven’s op.18 and was eventually to comprise only two complete works, Haydn’s creativity as a composer finally began to wane. On the recommendation of his biographer Griesinger, he eventually published the third, incomplete quartet in 1806 as his op.103 – a two-movement ‘farewell’ accompanied by a visiting card which bore the text, ‘All my strength is at an end, I am old and weak’. During the final years of his life, Haydn was visited by prominent figures from home and abroad and, as an honorary citizen of the City of Vienna, became a celebrated ‘national treasure’, who was awarded honorary degrees, medals and membership by many of the leading music societies in Europe.

He made his final public appearance on the occasion of his seventy-sixth birthday on 27 March 1808, when his oratorio The Creation was given in the Great Hall of the Old University in Vienna. The performance was attended by all the leading dignitaries of the city, and was conducted by Antonio Salieri (1750–1825).

Joseph Haydn died peacefully at his home in Gumpendorf on 31 May 1809, during Napoleon’s occupation of Vienna. He was interred in Hundsthurm cemetery on 1 June, and on the following day a Requiem Mass was celebrated in Gumpendorf Church. A great memorial service was held two weeks later at the Schottenkirche in Vienna, which was attended by the city’s elite. Haydn’s mortal remains have since been laid to rest in a mausoleum built at the Bergkirche in Eisenstadt in 1932 on the instructions of Prince Paul Esterházy.