NO.2 _IL FILOSOFO

Il Giardino Armonico

Giovanni Antonini, conductor

Bernhard Lassahn, writer

Chris Steele-Perkins, photographer

Symphonies No.22, No.46 and No.47

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach (1710–1784): Sinfonia in F Major

Program

Joseph Haydn (1732–1809): Symphony No.47 in G Major, Hob. I:47 (1772)

Allegro / Un poco adagio, cantabile / Menuetto e Trio al roverso / Presto assai

SYMPHONY NO.47 G MAJOR HOB. I:47 (1772)

Time of creation: till 1772

Allegro – Un poco adagio, cantabile – Menuetto e Trio al roverso – Presto assai

by Christian Moritz-Bauer

A completely different yet no less impressive dance movement is central to the Symphony in G major Hob. I:47, and earned it the occasionally applied nickname of ‘Palindrome’. Perhaps it was the ten minuet and twelve trio bars, which the composer then brings in al roverso, i.e. in mirror-inverted form, that appealed so much to W. A. Mozart that he wanted to perform the work at a musical academy in Vienna. This can be read in a hand-written note now owned by the Historical Society of Philadelphia.

The first movement, however, which survives in Haydn’s hand without a tempo indication, has its own special charm. Terrace-like overlapping fanfares give it the air of a ‘big c-major symphony’, and its dissonant tension-filled opening chords are contrasted by finely pointed violin interjections and sequences of ‘relaxed Schubertian’ triplets with a gentle oboe cantilene above them.

So the effect is indeed intense when the recapitulation suddenly opens in the opposite sex of G minor. The shock is thankfully brief and moreover lessened by the following variation movement with an extended coda – which may have been modelled on the second movement of no. 4 of the ‘Sun’ Quartets op. 20 – with a double counterpoint in the octave, fagotto sempres col basso, and gentle wind tones in the string-dominated middle sections. The note values decrease from variation to variation, building a bridge to the final presto assai, in which the quietly speeding string theme is contrasted by loud tutti passages, whose oddest ingredient must be the grace-note figure that the great Haydn scholar H. C. Robbins Landon, who died in 2009, once called the ‘Balkan snap’.

Although Hob. 1:47 is written in a more ‘normal’ key than the F-sharp minor of the Farewell Symphony or the B major of no. 46, it presents us with ‘a composer who is unwilling to be comfortable with tradition; each movement departs from the conventions of Haydn’s previous and the Viennese symphony in general.’

1 Sonja Gerlach considers it not impossible that Haydn was ‘influenced by a fashion’, and quotes a reference, dated 1770, from Johann Adam Hiller’s Musikalischen Nachrichten und Anmerkungen [Musical News and Notes], to ‘an artificial minuet, by Herr Capellmeister [Carl Philipp Emanuel] Bach in Hamburg’, which was presented ‘as a marvel’. See S. Gerlach, ‘Joseph Haydn’s Sinfonien bis 1774. Studien zur Chronologie’, in Haydn-Studien 7/1–2 (1996), p. 178.

2 Prince Nikolaus I. Esterházy also seems to have delighted in his kapellmeister’s games. Transposed into A major, it will be revived in a collection of piano sonatas presented to him on his sixtieth birthday.

3 Behind these could lie Haydn’s special affection for Johann May, who was promoted to 2nd horn in April 1772. This could certainly accord with Gerlach’s attempted dating of ‘early 1772’.

4 Ludwig Finscher, Joseph Haydn und seine Zeit, Laaber 2000, p. 279.

5 H. C. Robbins Landon, Haydn: Chronicle And Works, vol. II, Haydn at Eszterháza 1766–1790, London 1978, p. 305.

6 A. Peter Brown, The Symphonic Repertoire, vol. II, The First Golden Age of the Viennese Symphony: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert, Bloomington 2002, p. 139.

to the shop

Joseph Haydn (1732–1809): Symphony No.22 in E Flat Major, Hob. I:22 «The Philosopher» (1764)

Adagio / Presto / Menuetto. Trio / Finale: Presto

SYMPHONY NO.22 E FLAT MAJOR «THE PHILOSOPHER» HOB. I:22 (1764)

Time of creation: till 1767 [1761/1762]

Adagio – Presto – Menuetto. Trio – Finale: Presto

by Christian Moritz-Bauer

With the Symphony in E-flat major Hob. I:22 we return to the time in which Joseph Haydn still held the office of vice kapellmeister to Prince Esterházy, but in consideration of the advanced age of his superior, Gregor Joseph Werner, was already supplying the court with compositions of his own in all areas except sacred music.

The autograph of this work, dated 1764, stipulates (in contrast to most of its copies) a wind section of cors anglais (instead of the more usual oboes or flutes) and natural horns. The double-reeded cor anglais is a smaller version of the Baroque oboe da caccia, and has a pear-shaped bell. Haydn otherwise uses it, after the divertimenti of the eary 1760s (Hob. II:12, 16 and 24) and the present symphony, only in a few vocal compositions, such as the C-minor aria ‘Non v’è chi mi aiuta’, from La Canterina (1766), the Stabat Mater (1767) or the ‘Organ Solo Mass’ (1768/69).

If the orchestrational singularity of Hob. 1:22 (at least at the Esterházy court) was to go out of fashion within a few years, the symphony was the first – after the ‘times of day’ symphonies, of 1761 – to enjoy a nickname. ‘Le Philosoph[e]’ (The Philosopher/Il Filosofo) derives from a body of instrumental parts held in Modena – to be more exact from the title of some of its string duplicates – which was produced in Vienna in 1780 and probably later extended by musicians of the Dukes of Este (from the House of Habsburg).

Haydn scholars and connoisseurs have always been very divided as to the compositional qualities of Hob. 1:22; A. Peter Brown even ventured the opinion that the fame ‘it has been endowed with’ was only based on its exceptional instrumentation and ‘non-authentic title’, and that the work consequently ‘exceeds its compositional accomplishments’.

Who would not rather follow Robbins Landon, who writes of instrumental sounds of unbelievable beauty that are among some of Haydn’s ‘most original creations’ in his description of the opening adagio’s ‘combination of English and French horns, muted violins, lower strings, perhaps with a bassoon’?

According to Walter Lessing, the opening of the Philosopher, whose ‘continuous … quaver movement is underlined by the chorale-like melody of the winds, even has an ‘air of the antique’. We only have to think of the bars interwoven into the recapitulation, which sound very much like Corelli, with their downwardly gliding suspended dissonances over a sequential bass. But a look at the basso continuo and composition manuals published in Leipzig and Vienna by the now rather disregarded Johann Friedrich Daube (1730–1797) shows us that Haydn wasn’t only composing with an eye to the past here. Daube saw the idea of ‘freye Nachahmung’ (free imitation) as a characteristic of modern composition, and advocated the integration of the old ‘artificial’ style into the new ‘natural’ one.

Nothing seems more natural to Haydn, however, than to be guided during an act of creation by his ‘humour’, which should be understood – entirely according to the sensitivities of the time – as encompassing both his generally described cheerful attitude and certain situational frames of mind which critics were wont to call mere ‘Laune’ (moods).

A particular characteristic of Haydn’s humour – here of course quickened by the first and last appearance of the colour of the cors anglais – is shown in the presto second movement, which recalls the Salzburg works of his younger brother Johann Michael in its continual quavers and wealth of motifs in the string writing.

The leading position in this cheerful sound world is naturally taken by the first violins, who are not too proud to take on a supporting role, however, if their double-reeded colleagues, after laboriously gaining height, are to make the final triumphant semitone ascent to b flat''.

All the more astounding – after a momentary recovery in the divertimento-like minuet with its attendent rurally relaxed trio – is the spirited interplay between both pairs of horns in the 6/8 presto finale.

Although it was our composer’s habit to date his works imprecisely by the year only, extensive research has now made it possible to order the symphonies of 1764 in the following sequence: 23, 22, 21 and 24. So two works with a ‘normal’ structure (fast – slow – minuet – fast) frame two oriented to the sonata da chiesa.

In the same year of the Philosopher’s composition, more specifically in December 1764, there was a performance in the Kärntertortheater in Vienna – a predecessor of today’s Staatsoper – of a German-language adaptation of Il filosof inglese, by Carlo Goldoni, as Die Philosophinnen, oder Hanswurst der Cavalier in London zu seinem Unglück [The Lady Philosophers, or Pantaloon the Cavalier in London to His Misfortune].

Whether this included music from Hob. 1:22 – as suggested by Elaine Sisman – seems questionable, but certainly not impossible. An argument in favour could be the illuminating connection made by Nicolas Chamfort between Haydn’s later Symphony in F major Hob. 1:49 (‘La Passione’) and the ‘touching comedy’ La jeune Indienne, performed by Karl Wahr’s troupe of actors.

1 The name English horn probably derives from the instrument’s originally curved form, which recalled the angels’ horns in ecclesiastical illustrations.

2 Biblioteca Estense, sig. D.145 3 A. Peter Brown, The Symphonic Repertoire, vol. II – The First Golden Age of the Viennese Symphony: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert, Bloomington 2002, p. 89.

4 H. C. Robbins Landon, The Symphonies of Joseph Haydn, London 1955, p. 257f.

5 Walter Lessing, Die Sinfonien von Joseph Haydn, vol I, Baden-Baden, 1987, p. 82.

6 Generalbaß in drey Accorden, gegründet in den Regeln der alt- und neuern Autoren, Leipzig 1756; Der musikalische Dilettant, Vienna 1773; Anleitung zur Erfindung der Melodie und ihrer Fortsetzung, Vienna 1798.

7 See Felix Diergarten, ‘Anleitung zur Erfindung. Die Kompositionslehre Johann Friedrich Daubes’, in Musiktheorie 23 (2008), particularly pp. 312–313.

8 In the case of Symphony no. 22, Sonja Gerlach assumes that it was written down early than no. 21, but she also considers it to have been completed later. See Sonja Gerlach, ‘Joseph Haydns Sinfonien bis 1774. Studien zur Chronologie’, in Haydn-Studien 7/1-2 (1996), p. 110f. This ‘fact’ matches a payment order, dated ‘Eisenstadt, the 9th of July 764’, made out to a certain Mathias Rockobauer for the manufacture of reeds for oboes, bassoons and English horns.

9 Further symphonies by Haydn in the da chiesa form are numbers 4, 18, 34, 42 and 49.

10 Elaine R. Sisman, ‘Haydn's Theater Symphonies’, in the Journal of the American Musicological Society, 43

to the shop

Joseph Haydn (1732–1809): Symphony No.46 in B Major, Hob. I:46 (1772)

Vivace / Poco adagio / Menuet. Allegretto – Trio / Finale: Presto e scherzando

SYMPHONY NO.46 B MAJOR HOB. I:46 (1772)

Time of creation: [2nd half?] 1772

by Christian Moritz-Bauer

The Symphonies no. 46 and 47, which Joseph Haydn committed to paper in the year of his fortieth birthday while kapellmeister to Nicholas I, Prince Esterházy, are seen as a first pinnacle of his output, together with the ‘Farewell’ Symphony, the ‘Sun’ Quartets, later published as op. 30, and the ‘Mourning’ Symphony (written in 1770/71 and offered in the Breitkopf catalogue of 1772). They unite everything that a year and a half of systematic exploration of the ‘many different possibilities of … symphonic form and symphonic expression’ had brought to fruition and – as can be read in Griesinger’s Biographische Notizen – had met with the lasting approval of the prince.

Vivace / Poco adagio / Menuet. Allegretto – Trio / Finale: Presto e scherzando

Along with Hob. I:45 – according to the famous anecdote a musical request to Prince Nicholas to allow his musicians to return home to their families in Eisenstadt after too long at Eszterháza , the Symphony in B major Hob. 1:46, considered its sister work – James Webster, for example, calls them ‘a pair of programmatic works and refers to various modal and harmonic relationships – boasts, aside from its unusual accumulation of accidentals, a final movement that is not only equally as original but also increasingly takes on strange, even grotesque characteristics, inspiring some connoisseurs to compare it with its counterpart in Beethoven’s Symphony no. 5.

A quiet but boisterous theme, announced as a duet between the first and second violins, repeatedly comes to a standstill, despite several particularly striking tutti pedals and sequences. So, in the middle of the recapitulation, a part of the preceeding minuet movement can slip in and regularly get the upper hand – a ‘formal temerity’, in the opinion of Sonja Gerlach. At this point the dissolution of the ensemble brought about in the ‘Farewell’ Symphony seems almost a foregone conclusion. But then the horns ring out, calling for general order, to which the first violins strike up a relaxed variation of the theme, which is finally brought to a proper conclusion.

The presto e scherzando movement doesn’t stand alone in the irregularities of its motivic and thematic processes. The opening vivace is characterised by fast-paced musical thought, as with its first four-note motif, which is announced in unison and then combined in many different ways – with a contrapuntal countermelody, for example, or in canon with itself. And a dynamically exposed subsidiary idea, derived from a transition in the exposition section, which hijacks us into the ‘Farewell’ Symhony’s F-sharp minor and belies one or two listening habits …

The subsequent poco adagio, which moves between a rocking siciliano melody and softly scurrying semiquaver staccati, elicits mixed emotions. The tone of the allegretto minuet, by contrast, is comparatively ‘concrete’; its characteristic flights of quavers, which have often been thought of as (Baroque) sighing figures, but are basically nothing other than strings of appogiaturas (that is, a kind of gallant figuration), set the framework for a sombrely atmospheric trio section.

But how can the special sound world of Hob. 1:65 be expressed in words, and how can its creation be explained?

To a much greater degree than with ‘modern’ orchestras, with so-called old or original instruments the use of various keys not only affects the sounds they produce but also the feelings evoked in the audience. Although listeners can of course differ according to temperament, biography and living conditions, composers and theoreticians have endeavoured over the generations to describe generally valid characteristics associated with the respective ‘tones’. For example, in Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart’s famous Ideen zu Ästhetik der Tonkunst [Ideas on the Aesthetics of the Musical Art], written around 1784, the five-sharped B major is portrayed as ‘strongly hued, announcing wild passions, composed of the most garish colours’.

A particular quality of the symphonies Haydn composed between 1768 and 1772, which are traditionally described with the literary term ‘Sturm und Drang’, lies in the intensification of expression they achieve (not least through the use of numerous minor und rarely used keys), the result of compositional and instrumental experimentation. With two ‘semitone crooks’, tubing inserted into the still valveless horns to lower them from G or C alto to F sharp or B, invoiced on 22 October 1772, the store of natural tones was able to be extended. It is almost self-evident that this purchase must have a direct connection to the composition of the Symphonies no. 45 and 46.

In tonal terms, the sections in which the horns play in B major – the opening and closing movments and the minuet of the third movement – seem distinctly sharper (especially as the strings often play in only two parts or octaves) than the B-minor adagio and trio, for which the hornists apply D-crooks, which bring about mellower tones. According to Sonja Gerlach, ‘the fact that Haydn’s manuscript shows an anomalous, rarely found watermark could support the hypothesis of a [previous] change of location’, i.e. that the Symphony in B major was written down immediately after the completion of the ‘Farewell’ Symphony in autumn 1772.

1 ‘The [Farewell] Symphony was perhaps also intended to help against the prince’s plans [in the end abandoned] to reduce the size of the orchestra and cut salaries.’ Translated from Ludwig Finscher, Joseph Haydn und seine Zeit, p. 34.

2 ‘The [Farewell] Symphony was perhaps also intended to help against the prince’s plans [in the end abandoned] to reduce the size of the orchestra and cut salaries.’ Translated from Ludwig Finscher, Joseph Haydn und seine Zeit, p. 34.

3 ‘The [Farewell] Symphony was perhaps also intended to help against the prince’s plans [in the end abandoned] to reduce the size of the orchestra and cut salaries.’ Translated from Ludwig Finscher, Joseph Haydn und seine Zeit, p. 34. 4 James Webster, Haydn’s ‘Farewell’ Symphony and the Idea of Classical Style, Cambridge 1991, p. 287.

5 Haydn, who theoretically could have attended the performance of a symphony in B major by Georg Matthias Monn during his time as a choirboy at St Steven’s in Vienna, wrote no other works in this remote key apart from a now lost piano sonata.

6 Sonja Gerlach, ‘Joseph Haydns Sinfonien bis 1774. Studien zur Chronologie’, in Haydn-Studien 7/1–2 (1996), p. 180.

7 Ludwig Finscher attributes to it a close relationship to the main them of the first movement of the Symphony in E-flat minor no. 44, which resembles its inversion.

8 Sonja Gerlach, ‘Joseph Haydns Sinfonien bis 1774. Studien zur Chronologie’, in Haydn-Studien 7/1–2 (1996), p. 159.

to the shop

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach (1710–1784): Sinfonia in F Major

Vivace / Andante / Allegro / Menuetto I alternativement – Menuetto 2 – Menuetto 1 da capo

WILHELM FRIEDEMANN BACH (1710–1784): SINFONIA F MAJOR C2 FK 67

Vivace / Andante / Allegro / Menuetto I alternativement – Menuetto 2 – Menuetto 1 da capo

by Christian Moritz-Bauer

As with the hunting piece of Haydn’s Symphony no. 22, a work for strings composed by Bach’s eldest son during his time in Dresden (1733–1746) also combines old and new compositional ideas – one of them being the traditional three-part form of the Italian opera sinfonia, which in the manner of the suite is given an additional minuet movement with a canonic middle section that according to Peter Wollny ‘was apparently a favourite of Wilhlem Friedemann’. Often appearing in other contexts [such as the Harpsichord Sonata in C major Fk 1A], it seems to be filled with the spirit of Georg Friedrich Händel in its calm, festive tone.

The minuet is preceded by a music that – to return once again to the words of Johann Friedrich Daube – never shies away from a powerful contrast in the ‘alteration and division of its melodic elements’, and can even sound strange to experienced ears: a vivace that begins like a Baroque overture but is soon invaded by increasingly bold leaps, sudden semiquaver repetitions and rhythms rutted with pauses that seem to ‘owe much to the instrumental style of Jan Dismas Zelenka’; an andante whose falling arpeggios and chains of chromatic suspensions recall contemporary works for the stage by Johann Adolf Hasse, for example; an allegro characterised by echo effects, striking rhythms and dynamic contrasts.

Although the work of Friedemann Bach, much of which has been lost, traditionally plays no special role in the development of the classical symphony – particularly because even into the composer’s final years in Berlin it was not much distributed – today it has the reputation of being a noticeably early form of the so-called sensitive style, which was to become the trademark of his brother Carl Philipp Emanuel and earn him much greater fame.

1 Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, Collected Works, vol. 6, Orchestral Music III: Symphonies, ed. Peter Wollny, Stuttgart 2010, p. VI.

2 The resulting sequence of movements corresponds almost exactly to Johann Sebastian Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto no. 1, also in F major.

3 Translated from Johann Friedrich Daube, Der musikalische Diletantt: eine Abhandlung der Komposition, Vienna 1773, p. 162.

4 Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, Collected Works,op cit., p. VI.

5 See Marc Vignal, Die Bach-Söhne: Wilhelm Friedemann, Carl Philipp Emanuel, Johann Christoph Fiedrich, Johann Christian, Laaber 1999, p. 52ff.

to the shop

Line-up

Il Giardino Armonico

Giovanni Antonini, conductor

- Line-up orchestra

1st violins _Stefano Barneschi*, Fabrizio Haim Cipriani, Ayako Matsunaga, Liana Mosca

2nd violins _Marco Bianchi*, Francesco Colletti, Judith Huber, Maria Cristina Vasi

Violas _ Ernest Braucher*, Carlo De Martini

Celli _Paolo Beschi*, Elena Russo

Basses _Giancarlo De Frenza*, Stefan Preyer

Oboes _Emiliano Rodolfi*, Josep Domenech

Bassoon _Alberto Guerra

Horns _Glen Borling*, Edward Deskur

Harpsichord _Riccardo Doni

Past concerts

Basel

Wednesday, 06.05.2015, 19.00 pm

Haydn Night at the Martinskirche, Basel

During his lifetime, Haydn was celebrated as a musician throughout Europe. Mr. Haydn’s Nights took place regularly in London’s Hanover Square – and events they certainly were! In the eighteenth century the concert was considered a festive gathering, a happy affair and a social occasion.

This idea will be taken up by the Haydn Nights and transported into today. Not only will the symphonies be performed: Discussions, opportunities to stroll around and talk, photographic installations and gastronomic treats make for a unique concert experience.

Berlin

Friday, 08.05.2015, 19.00 pm

Radiale Nacht Haydn2032 «Il Filosofo» at the Radialsystem V., Berlin

Eisenstadt

Saturday, 09.05.2015, 19.30 pm

Haydn Night at Schloss Esterházy, Haydnsaal, Eisenstadt

Biographies

Orchestra

Il Giardino Armonico

Orchestra

Founded in 1985 and conducted by Giovanni Antonini, has been established as one of the world’s leading period instrument ensembles, bringing together musicians from Europe’s relevant music institutions. The ensemble’s repertoire mainly focuses on the 17th and 18th century. Depending on the demands of each program, the group consists of three up to thirty musicians.

Il Giardino Armonico is regularly invited to festivals all over the world performing in the most important concert halls, and has received high acclaim for both concerts and opera productions, like Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo, Vivaldi’s Ottone in Villa Händel’s Agrippina, Il Trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno, La Resurrezione and finally Giulio Cesare in Egitto with Cecilia Bartoli during the 2012 edition of the Salzburg Whitsun and Summer Festival.

Beside that, Il Giardino Armonico sustains an intense recording activity. After many years as an exclusive group of Teldec Classics achieving several major awards for its recordings of works by Vivaldi and the other 18th century composers, the group had an exclusive agreement with Decca/ L’Oiseau-Lyre recording Händel’s Concerti Grossi Op. VI and the cantata Il Pianto di Maria with Bernarda Fink.

The group also released on Naïve La Casa del Diavolo, Vivaldi cello Concertos with Christophe Coin, and the opera Ottone in Villa winning the Diapason d’Or in 2011. On the label Onyx Vivaldi violin Concertos with Viktoria Mullova.

In 2009 a new cooperation with Cecilia Bartoli led to the project Sacrificium (Decca), Platinum Album in France and Belgium and prized by the Grammy Award.

Again on Decca Alleluia (March 2013) and Händel in Italy (October 2015) with Julia Lezhneva, acclaimed by public and critics.

The group published Serpent & Fire with Anna Prohaska (Alpha Classics – Outhere music group, 2016) winning the ICMA “baroque vocal” in 2017.

The recording of five Mozart Violin Concertos with Isabel Faust (Harmonia Mundi, 2016) stands as the result of the prestigious cooperation with the great violinist.

Il Giardino Armonico is part of the twenty-year project Haydn2032 for which the Haydn Foundation has been created in Basel to support both the recording project of the complete Haydn Symphonies (Alpha Classic) and a series of concerts in various European cities, with thematic programs focused on this fascinating repertoire. In November 2014 the first album titled La Passione has been published and won the Echo Klassik award in 2015. Il Filosofo, issued in 2015, has been “CHOC of the year” by Classica. The third one Solo e Pensoso has been released in August 2016, and the forth Il Distratto in March 2017.

The last volumes of the Haydn2032 project, as well as Telemann (Alpha Classics, November 2016) are available as CD and LP too. Telemann won the Diapason d’Or in January 2017.

Furthermore the ensemble worked with such acclaimed soloists as Giuliano Carmignola, Sol Gabetta, Katia and Marielle Labèque, Viktoria Mullova, and Giovanni Sollima.

Conductor

Giovanni Antonini

Conductor

Born in Milan, Giovanni studied at the Civica Scuola di Musica and at the Centre de Musique Ancienne in Geneva. He is a founder member of the Baroque ensemble “Il Giardino Armonico”, which he has led since 1989. With this ensemble, he has appeared as conductor and soloist on the recorder and Baroque transverse flute in Europe, United States, Canada, South America, Australia, Japan and Malaysia. He is Artistic Director of Wratislavia Cantans Festival in Poland and Principal Guest Conductor of Mozarteum Orchester and Kammerorchester Basel.

He has performed with many prestigious artists including Cecilia Bartoli, Kristian Bezuidenhout, Giuliano Carmignola, Isabelle Faust, Sol Gabetta, Sumi Jo, Viktoria Mullova, Katia and Marielle Labèque, Emmanuel Pahud and Giovanni Sollima. Renowned for his refined and innovative interpretation of the classical and baroque repertoire, Antonini is also a regular guest with Berliner Philharmoniker, Concertgebouworkest, Tonhalle Orchester, Mozarteum Orchester, Leipzig Gewandhausorchester, London Symphony Orchestra and Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

His opera productions have included Handel’s Giulio Cesare and Bellini’s Norma with Cecilia Bartoli at Salzburg Festival. In 2018 he conducted Orlando at Theater an der Wien and returned to Opernhaus Zurich for Idomeneo. In the 21/22 season he will guest conduct the Konzerthaus Orchester Berlin, Stavanger Symphony, Anima Eterna Bruges and the Symphonieorchester de Bayerischer Rundfunks. He will also direct Cavalieri’s opera Rappresentatione di Anima, et di Corpo for Theatre an der Wien and a ballet production of Haydn’s Die Jahreszeiten for Wiener Staatsballett with the Wiener Philharmoniker.

With Il Giardino Armonico, Giovanni has recorded numerous CDs of instrumental works by Vivaldi, J.S. Bach (Brandenburg Concertos), Biber and Locke for Teldec. With Naïve he recorded Vivaldi’s opera Ottone in Villa, and, with Il Giardino Armonico for Decca, has recorded Alleluia with Julia Lezhneva and La morte della Ragione, collections of sixteenth and seventeenth century instrumental music. With Kammerorchester Basel he has recorded the complete Beethoven Symphonies for Sony Classical and a disc of flute concertos with Emmanuel Pahud entitled Revolution for Warner Classics. In 2013 he conducted a recording of Bellini’s Norma for Decca in collaboration with Orchestra La Scintilla.

Antonini is artistic director of the Haydn 2032 project, created to realise a vision to record and perform with Il Giardino Armonico and Kammerorchester Basel, the complete symphonies of Joseph Haydn by the 300th anniversary of the composer’s birth. The first 12 volumes have been released on the Alpha Classics label with two further volumes planned for release every year.

Recordings

VOL. 2 _IL FILOSOFO

CD

Giovanni Antonini, Il Giardino Armonico

Symphonies No.22, No.46 and No.47

W. F. Bach: Sinfonia in F-Major

Available at:

Bider&Tanner, Basel

Outhere Music

Download

Stream

VOL. 2 _IL FILOSOFO

Vinyl-LP with book (download code CD included)

Giovanni Antonini, Il Giardino Armonico

Symphonies No.22, No.46 and No.47

W. F. Bach: Sinfonia in F-Major

Essay "Haydn – Originality" by Bernhard Lassahn

Available at:

Bider&Tanner, Basel

Joseph Haydn Stiftung, Basel

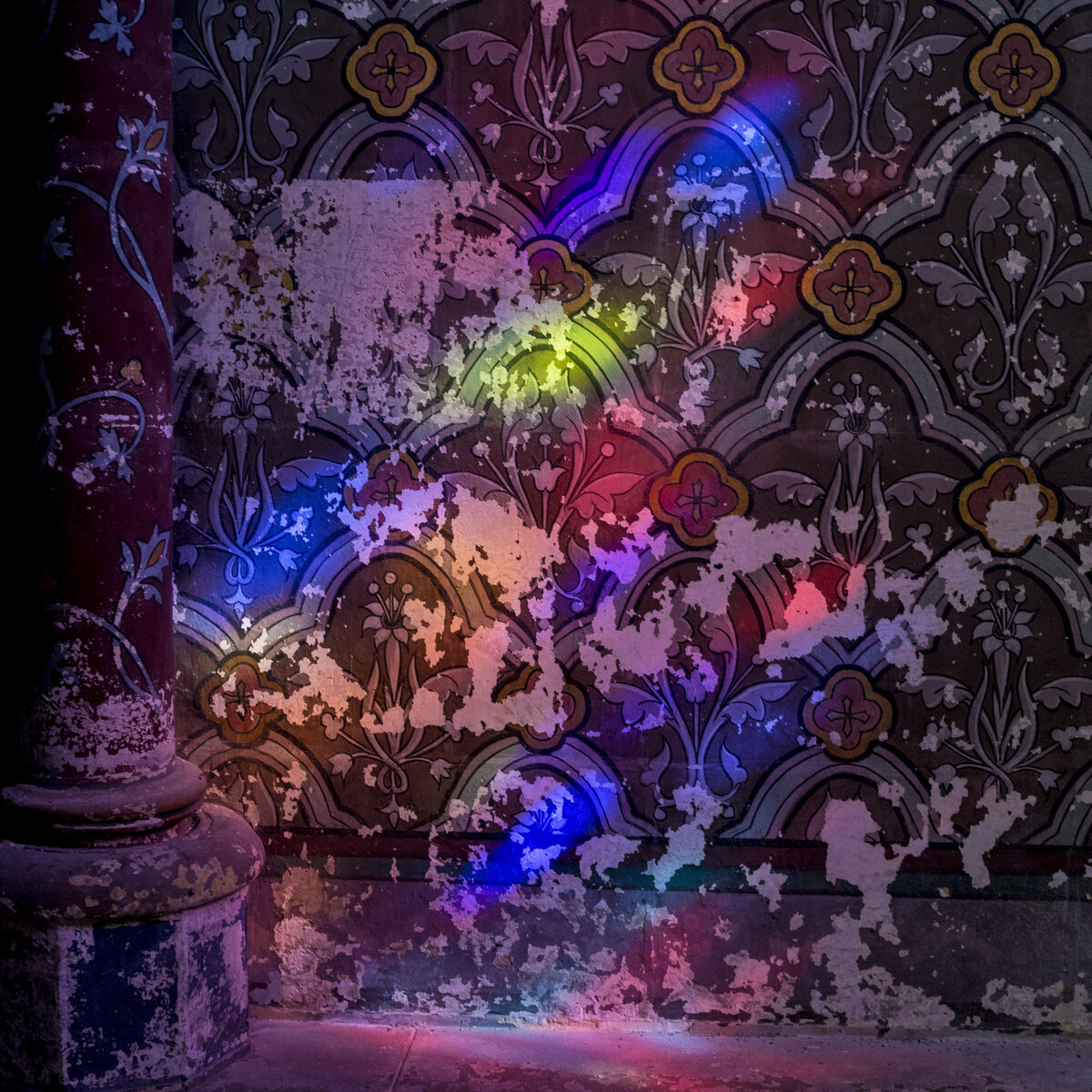

© Chris Steele-Perkins / Magnum Photos

Biography

Photographer, Magnum Photos

Chris Steele-Perkins

Photographer, Magnum Photos

At the age of two Chris Steele-Perkins left Burma for England. Later he graduated in psychology and taught himself photograph, starting to work as a freelance photographer in 1971. He worked mainly in Britain in areas concerned with urban poverty and subcultures. His social work led him to join Parisian Viva agency in 1976, and Magnum Photos agency in 1979. Apart from his work on Britain, he has worked a lot in Afghanistan, Africa, and Japan.

The essay "Haydn – Originality" by Bernhard Lassahn was published in the vinyl edition vol. 2.

Biography

Writer

Bernhard Lassahn

Writer

Bernhard Lassahn is a German author, singer songwriter and cabaret artist. He is the first laureate of the cabaret award «Salzburger Stier» and member of the German P.E.N. association. Along with Walter Moers and Rolf Silber he wrote the stories around Captain Bluebear for «Die Sendung mit der Maus» (The Program with the Mouse). He is the author of the highly acclaimed novel «Aboard the black ship».

Lassahn lives in Berlin and performs regularily at poetry readings of Zebrano Theatre. He is also author for «The Axis of the Good» and «Cuncti» blogs.