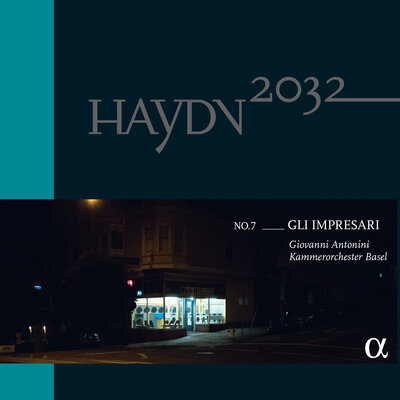

NO.7 __GLI IMPRESARI

Basel Chamber Orchestra

Giovanni Antonini, conductor

Daniel Kehlmann, writer

Peter van Agtmael, photographer

Joseph Haydn: Symphonies No.9, No.65 and No.67

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Thamos. King of Egypt

Every year from 1769 until the death of Prince Nicholas I Esterházy, touring theatre companies under the direction of a manager (Italian: impresario) – in one case, two managers – were engaged for a season of performances at the renowned Eszterháza Palace, his summer residence south-east of Lake Neusiedl (Fertő); the contracts might be prolonged for one or more years if the Prince was satisfied with the players. In the early years, the season usually lasted from the beginning of May to the middle or end of October. From 1776 onwards – when the drama, ballet and singspiel performances given by the visiting troupes were joined by a regular repertory of Italian opera performed by the Prince’s own salaried singers – that period was extended to February to November. (Moreover, there was also the troupe catering to the needs of the palace’s marionette opera, which was set up in 1773 but only lasted until 1783.)

In addition to various details on the composition of the theatre companies, the performance modalities (the troupe was ‘ to perform a play every day at any place and hour to be determined by [the Prince], on a subject matter to be decided by the impresario, and to supply the necessary costumes and plays’) and the fees and accommodation for the actors, it was stipulated that ‘[t]he music for the rehearsals of their plays or pantomimes, and the lighting, sets, and small prerequisites for the theatre . . . [are to be] provided at His Highness’s expense’. As a result, the musical content of the plays, which usually called for an overture, several entr’actes varying according to the number of acts in the play, and a final sinfonia, became a matter for the Prince’s musical establishment (Hofkapelle) and its Kapellmeister Joseph Haydn.

But how should we picture the musical side of this theatrical activity, which took place in the architectural setting of the splendid opera house and (for a time) also the puppet theatre located opposite the palace buildings? As was common practice in the theatre of the time, the ‘music between the acts’ heard at Eszterháza was probably not originally written for the dramatic works given there, let alone composed by Haydn himself. Nevertheless, in his role as musical director, he does seem to have been commissioned by his employer to contribute original music directly linked to the spoken (and sometimes danced) stage action on certain outstanding occasions, for instance when a high-ranking personage came to visit the Prince.

Program

Joseph Haydn (1732–1809): Symphony No.9 in C Major, Hob. I:9 (1762)

Allegro molto / Andante / Menuetto. Allegretto – Trio

SYMPHONY NO. 9 IN C MAJOR HOB. I:9 (1762)

Time of creation: [spring?] 1762

Allegro molto / Andante / Menuetto. Allegretto – Trio

[Impresario: Girolamo Bon]

With the first and earliest of the three theatrical symphonies by Joseph Haydn assembled here under the title ‘Gli Impresari’, we take a look back – back to the time when Prince Nicolaus had just succeeded his older brother Paul Anton as head of the magnate family of Esterházy de Galántha. On 12 May 1762, just five days before his solemn induction, a group of ‘Welsche Komödianten’ (Italian actors) had taken up quarters at the Wirt zum Greifen (Griffin Inn) in Eisenstadt (in Hungarian, ‘Kismarton’), where they were to remain until June of the same year and perform the comedies La marchesa Nespola, La vedova, Il dottore and Il sganarello, all listed in Haydn’s Entwurfkatalog. Haydn scholars conjecture that the troupe of players was probably headed by a certain Girolamo Bon, pittore Architetto e Direttore dell’Opera ([stage] painter and designer and opera director). The same multi-talented artist, who had already found his way from his native city of Venice to assorted theatrical functions in St Petersburg, Berlin, Dresden, Potsdam, Antwerp, Frankfurt and Regensburg, among other places, was taken into Prince Esterházy’s service at the beginning of July, along with his wife and daughter. In addition to the vocal qualities of Rosa Ruvinetti-Bon and the instrumental and compositional skills of Anna (Lucia) Bon, who was born in Bologna and had trained at the Ospedale della Pietà in Venice, another decisive factor in their engagement was probably Bon’s teaching activity of the head of the family at the Akademie der Schönen Künste (Academy of fine arts) in Bayreuth from 1756 to 1761. He combined his work as painter and set designer with writing for the theatre, for example as the (conjectural) arranger of the libretti for Haydn’s early Italian operas La canterina, Lo speziale, Le pescatrici and L’infedeltà delusa or of the homage cantatas for Nicolaus I and his son Anton written between 1763 and 1767.

The Symphony in C major Hob. I:9, composed in 1762, seems to have a specific connection with another such cantata, which was rediscovered by Irmgard Becker-Glauch in the form of a Latin motet.1 The three-movement work may once have served – with different instrumentation – as an orchestral prelude to the putative cantata. This would also explain the strange corrections in the indications of the orchestral forces, which suggest it was originally played with timpani, clarino trumpets and/or horns and strings, but without oboes (!). In the symphony’s autograph, which only came to light again in 2000 and is held at the Paul Sacher Foundation in Basel, this scoring was finally changed to oboes/flutes, horns, bassoon and strings.2

Whether the C major Symphony was once intended as the prelude to a cantata or a comedy, or rather for the princely chamber, in terms of character and dramaturgical structure it would be well suited to the atmosphere and period when Nicolaus I Esterházy assumed his position as head of the family. It consists of an Allegro molto that ‘eschews strongly profiled themes in favour of three-chord hammer strokes, wind fanfares, constant bustle and rhythmic surprise’ (James Webster),3 a pastoral Andante, and an Allegretto minuet with waltz-like string accompaniment to the blissful solo oboe melody in the first strain of the Trio and the wind quintet interlude, reminiscent of Feldmusik for military band, in the second.

1 ‘Quis stellae radius’, Hob. XXIIIa:4 [sometimes referred to as ‘Motetto de Sancta Thecla’ – translator’s note]. See Irmgard Becker-Glauch, ‘Neue Forschungen zu Haydns Kirchenmusik’, Haydn-Studien II/3 (May 1970), pp.167 – 241, especially pp.177 – 83.

2 See Sonja Gerlach, ‘Das Autograph von Haydns Sinfonie Hob. I:9 aus dem Jahr 1762’, Haydn-Studien VIII/3 (September 2003), pp.217– 36.

3 James Webster, ‘Early Esterházy Symphonies, 1761-1763’, booklet note to the three-CD set ‘Haydn Symphonies, volume 3’ (London: Decca-L’Oiseau-Lyre, 433 661-2, 1992), p.24.

to the shop

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791): Thamos. King of Egypt KV 345/336a

Maestoso – Allegro / Andante / Allegro – Allegretto (melodrama) / Allegro vivace assai / Without tempo indication (Pheron’s despair, blasphemy and death)

W. A. MOZART: MUSIC FOR THAMOS, KÖNIG IN EGYPTEN K345/336a: nos. 2-5 & 7a (Salzburg, 1775/76)

Nr. 2-5 & 7a (Salzburg, 1775/76)

Maestoso – Allegro / Andante / Allegro – Allegretto (Melodram) / Allegro vivace assai / Without tempo indication (Pheron’s despair, blasphemy and death)

[Impresario: Carl Wahr]

Around the turn of the year 1775/76 – at about the time when Haydn was engaged in transforming his music for Die Jagdlust Heinrich des Vierte into a concert symphony – Carl Wahr enjoyed a success at the Theater im Ballhaus in Salzburg. The heroic drama Thamos, König in Egypten (Thamos, King of Egypt), written by Baron Tobias von Gebler, was staged there on 3 January 1776 with musical accompaniment by the court orchestra of the Prince Archbishop under the direction of Michael Haydn, Joseph’s younger brother. The music for the drama was mentioned in the press (something by no means common at the time), even though the Theaterwochenblatt für Salzburg restricted its remarks to the dismissive comment that the ‘composer of the choruses . . . has extended the fifth act excessively with repetitions’. That ‘composer’ – as research has since demonstrated with certainty – was none other than Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who had already written an early version of the aforementioned choruses on commission from the playwright during his stay in Vienna from July to September 1773. Various studies in the specialist field of the chronology of the handwriting and watermarks of Mozart’s autograph have confirmed that, in addition to these vocal numbers integrated into the stage action, the Salzburg performance in question also included four instrumental interludes between the acts, along with a melodrama, and a musical descent into hell ‘à la Don Juan’, all composed especially for that later occasion, which took place on the Catholic feast of the Holy Name of Jesus. The same research has also established that the surviving autograph must have been written in a period that can be situated between around April 1775 and July 1776.1

The scene is set in ancient Egypt. Ramasses has deposed King Menes from his throne; the latter has not been seen since and has therefore been declared dead. In fact, disguised as the Chief Priest Sethos, he has withdrawn behind the protective walls of the Temple of the Sun. Unbeknownst to him, Tharsis, his daughter and heiress, is also serving in the temple under the borrowed name of Sais. She secretly loves Ramasses’s son Thamos, who is to ascend the throne after his father’s death.

The action now begins to unfold. The treacherous Pheron, whom Thamos disastrously considers to be one of his closest friends and advisers, sets out to influence the forthcoming process of accession to the throne in his favour (Maestoso - Allegro). The syncopations that dominate the musical texture underline the constantly increasing drama. The second act concludes with music (Andante) which – according to the abbreviated annotations to the autograph score in Leopold Mozart’s hand – contrasts the fundamentally honest character of Thamos (represented by solo oboe) with the falseness of Pheron (the two bassoons answering the oboe in thirds).

Pheron foments a conspiracy against Thamos. With the help of his accomplice Mirza, the highest-ranking Virgin of the Sun, he seeks to win Tharsis’s affection in order to obtain the throne for himself through marriage, using any means – including the lie that Thamos in reality loves a certain Myris and (worse still) has chosen Pheron to marry ‘Sais’. But, in order to defend herself from her supposed fate of marrying Pheron, the maiden decides – resorting to the dramatically heightened device of melodrama – to consecrate herself to the gods as a Priestess of the Sun (Allegro - Allegretto).

Once Pheron has realised that his plan is doomed to failure, he tries to conquer the throne by force of arms. Thamos in turn understands that he and Sais/Tharsis have been deceived. The fourth act closes in a situation of ‘general confusion’ (Allegro vivace assai).

The moment has come for Menes, the old king, to reveal himself and order the arrest of Pheron. Cheated of her last chance of success, Mirza stabs herself, while Pheron, having cursed the gods, is struck by lightning (‘Pheron’s despair, blasphemy and death’, without tempo marking). Sethos unites Thamos with Tharsis, whose vow to become Priestess is invalid because it was sworn without her father’s consent, and declares the couple to be the rightful heirs to his lost throne, which they are to take up immediately.

1 On this subject, see notably Alfred Orel, ‘Mozarts Beitrag zum deutschen Sprechtheater: die Musik zu Geblers Thamos’, Acta Mozartiana 4 (1957), pp.43-53, 74-81; Harald Heckmann, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Neue Ausgabe sämtlicher Werke. Serie II, Werkgruppe 6, Band 1: Chöre und Zwischenaktmusiken zu Thamos, König in Ägypten. Kritischer Bericht (Kassel and Basel: 1958), pp.4-7; Alan Tyson, Wasserzeichen-Katalog (Kassel and Basel: 1992 = W. A. Mozart. Neue Ausgabe sämtlicher Werke. Serie X, Werkgruppe 33, Abt. 2, Teilband 1), pp.

to the shop

Joseph Haydn (17532–1809): Symphony No.67 in F Major, Hob. I:67 (1774/75)

Presto / Adagio / Menuet – Trio / Finale. Allegro di molto – Adagio e cantabile – Allegro di molto

SYMPHONY NO. 67 IN F MAJOR HOB. I:67 (1775/1776)

Time of creation: till 1779 [1775/1776]

= Music for the comedy Die Jagdlust Heinrich des Vierten (Eszterháza, June/July 1772?)

Presto / Adagio / Menuet – Trio / Finale. Allegro di molto – Adagio e cantabile – Allegro di molto

[Impresario: Carl Wahr]

The years from 1772 onwards, when Carl Wahr (1745-1811) was responsible for the summer theatre programme, seem to have marked a highpoint in the ‘interdisciplinary’ collaboration between Prince Nicolaus I Esterházy’s court musical establishment, directed by Haydn, and troupes of actors engaged from elsewhere.1 This was precisely the period of the genesis and early performance history of the music for Der Zerstreute, a German translation of Jean-François Regnard’s comedy Le Distrait (The absent-minded gentleman, 1697), which has already formed the focus of an earlier Haydn2032 project (no.4, IL DISTRATTO). But there was also a similar festive event in the very first months after Wahr’s troupe embarked on their season, on the occasion of a visit from the French ambassador Louis René Édouard de Rohan. György Bessenyei, a grenadier officer who doubled as a court chronicler writing in Hungarian, began his account of the festivities with the following verses:

So the Prince de Rohan comes into the palace building; / His escort accompanies him into a large chamber.

A stage has been erected there, / Where the heart is turned towards tender sentiment.

The French King Henry the Fourth was shown hunting / For Prince Rohan’s pleasure.

These lines demonstrate that the play performed by Carl Wahr and his twelve-member ensemble – among them his habitual stage partner Sophie Körner – was, exceptionally, performed not in the separate theatre building but in the Sala Terrena or in the Prunksaal (state room) located on the first floor of the palace. They also inform us that the piece must have been Die Jagdlust Heinrich des Vierten (Henry IV’s passion for the chase), a translation by Christian Friedrich Schwan of La Partie de chasse de Henri IV, the comedy of character and manners by the French dramatist Charles Collé. This relates a story of a monarch and a nation that had just emerged from one of the most violent confessional and political conflicts in the history of Europe – the Wars of Religion between Catholics and Huguenots. Here is a summary of the plot:

Henry IV, King of France, has grown weary of the web of intrigues spun around his minister, the Duc de Sully, at the court of Fontainebleau, and calls on friend and foe alike to join in a deer hunt for the sake of mutual reconciliation. Thanks to the cunning of the game it is pursuing, the outbreak of a thunderstorm and the onset of darkness, the hunting party gets lost and its members lose touch with each other, until they are spotted and rescued by the inhabitants of the nearby village of Lieursain. Henry ends up in the care of the miller Michau, from whom and whose family he hides his identity, in order to convince himself of their loyalty to the crown but also to be able once again to follow his natural tendencies towards both magnanimity and libertinage. When he learns that the Marquis de Conchiny has abducted Agathe, the fiancée of the miller’s son Richard, he punishes the nobleman, who is also Sully’s greatest enemy. He thereupon decides to gratify the double wedding arranged for the following day between Agathe and Richard, and his sister Catau and Lucas, a poor young farmer, with a gift of 10,000 florins to each couple, and to serve as best man for both into the bargain.

This festive occasion in the summer of 1772 was of course to be followed by further performances of Die Jagdlust, including one per season just in Pressburg and Salzburg, where Wahr’s company set up winter quarters in 1773/74, 1774/75 and 1775/76. Moreover, the successful play was probably given again at Eszterháza at least once a year between May and October of the years between 1773 and 1776. (In the summer of 1777 the engagement of Carl Wahr and his troupe was prematurely terminated, after they had fallen out of favour with Prince Nicolaus on account of a serious offence committed by two of the members, further details of which are unknown.)

The correspondents of the Preßburger Zeitung and the Theaterwochenblatt für Salzburg tell us nothing about the music for the performances mentioned above. And yet connections can be discerned between Collé’s comedy and the multi-movement incidental music rediscovered by the author of this article in one of Haydn’s symphonies of the 1770s – connections of various kinds which theatregoers could perceive, decipher and, by means of their individual imaginations, translate into new contents that interpret, anticipate or even retell the action on stage.

The fact that this process may have been much easier for Haydn’s contemporaries than it is for a modern audience (however well-educated) is due not least to their respective experience as listeners, which has been modified by subsequent socio-cultural and technical developments in such a way that we first have to relearn or re-impart numerous ‘markers of the past’ in order to understand or make accessible the music of another era and its ability to communicate non-musical elements.

Seen from this intellectual standpoint, the opening Presto, which has hitherto been considered ‘only’ as the first movement of the Symphony no.67 in F major, which in that form is dated around 1775/76, may now appear – thanks to its rediscovered theatrical context – as an overture that reviews the whole of the stage action to come. Take, for example, the hunting motif oddly introduced pianissimo by the first violins, which is a quite deliberately distorted variant of the bugle signal ‘Retraite de soir’ (the Retreat or Tattoo, sounded in the evening to call soldiers back to camp) and probably looks forward to a later highpoint of the plot, the moment when family of the miller Michau offer their hospitality to the King, who tries in vain to preserve his incognito; or the ephemeral cloud cast over the boisterous ‘hunt’s up’ mood by a minor-key passage imbued with tragic undertones. There is also a foretaste of the evening song of the ‘simple people’, underpinned by the drone of the unison horns, at the start of the second half of the movement.

In the Adagio – which would correspond to the music for the second act – short, rhythmically concise motifs, which taken together generate a melodic texture interspersed with quaver and semiquaver rests, play an imaginary game of hide and seek of the kind the play’s protagonists more or less voluntarily take part in when, after the royal hunting party has lost its way in the woods, its members try to find each other again in the ever denser undergrowth as night falls. How does that sound in music? It rustles and crackles, exactly as when muted gut strings are maltreated with the wood of the bow – and, naturally, staccato and pianissimo! The King who, having been run to ground not by the feared poachers, but by the decent village miller, is then regaled in his honest parlour – completely incognito, of course – by (apple) wine, women (the miller’s wife and daughter) and, it goes without saying, song – this delicious spectacle of two colliding worlds, which takes up no fewer than twelve of a total of fourteen scenes in the third and last act of Collé’s comedy, finds its compositional counterpart in the minuet. The ingredients used here are a soloist from the ranks of the second violins, who retunes his or her G string to F before the start of the movement; an eight-bar strain followed by a second of six bars plus eight-bar reprise, which could hardly sound more courtly; and a ‘trio’ of two solo violins, the first playing a folk melody on one string with a good many ‘squeaky’ notes, the other playing a two-part drone bass.

The revelation that the seemingly sudden recognition of their ‘good King’ was in fact a clever plan of the miller’s family, aimed at freeing their future daughter-in-law Agathe from the clutches of the wicked, parasitical courtier Conchiny, is saved for the very end. This (along with many other things) suggests that the music of the concluding Allegro di molto portrays the wedding celebrations announced in the last lines of the play. Because we are dealing with a double wedding, uniting Agathe (who has freed herself from her unwelcome abductor) with her miller’s son Richard, and the latter’s wily sister Catau with her poor young farmer Lucas, and since Henry IV declares himself willing to act as best man and financial benefactor, there is also an inserted Adagio e cantabile middle section with solo sections for two violins and cello, later two oboes and bassoon, and, to crown it all, three rousing ‘cheers’ from the orchestral tutti.

Haydn was to use the beginning of the oboe and bassoon trio again only a few months after what one must still call the hypothetical first performance of his Jagdlust music, in the Kyrie of the Missa Sancti Nicolai Hob. XXII:6, composed for Prince Esterházy’s name day on 6 December 1772. This might be seen as an act of special reverence: a musical comparison of Nicolaus I Esterházy de Galántha with Henry IV, King of France and Navarre, and grandfather of the Sun King Louis XIV.

1 See James Webster, Hob.I:67 Symphonie in F-Dur: http://www.haydn107.com/index.php?id=2&sym=67&lng=1 (consulted 10 September 2017)

to the shop

Joseph Haydn (1732–1809): Symphony No.65 in A Major, Hob. I:65

Vivace con spirito / Andante / Menuet – Trio / Finale. Presto

SYMPHONY NO.65 IN A MAJOR HOB. I:65 (1769)

Time of creation: till 1778 [1769]

Music for Der Postzug oder die edlen Passionen, comedy by Cornelius von Ayrenhoff

Vivace con spirito / Andante / Menuet – Trio / Finale. Presto

[Impresari: Joseph Hellmann & Friedrich Koberwein]

Times can change so fast! In October 2017 the Symphony in A major Hob. I:65 was still being performed in Haydn2032 concerts as ‘Music for an unknown play’. As one of the chief suspects among those Haydn orchestral works whose conjectural origins might lie in incidental music for spoken theatre productions, it was given pride of place in the concert programme no.9, GLI IMPRESARI. But then, only a few weeks after the final Haydn Night in Rome, the author of these lines suddenly had before his eyes the decisive clue to the origin and intention of all those compositional idiosyncrasies which seem to adhere to the work like a ‘whiff of greasepaint’:1 an entry in the diary of Carl Johann Christian von Zinzendorf.

Count Zinzendorf, whose journal offers ‘a rich insight into the network of European elites and mentalities, into the world of books, theatres and opera houses’,2 had travelled to the heart of the ‘Esterházy Fairy Kingdom’ on 28 May 1772. The programme that awaited him there consisted of a festive reception followed by a concert under the direction of Joseph Haydn, who ‘played the violin’, and a tour of the park and palace. The entertainments were to culminate in a theatrical performance in the princely ‘Salle des Spectacles’,3 at which a certain ‘Postzug’ was given. The author of this play was Cornelius Hermann von Ayrenhoff (1733-1819), an officer in the Imperial and Royal Army. Pursuing his passion for the stage, he became one of the most successful playwrights in late eighteenth-century Vienna.4 Following its premiere on 30 September 1769 at the Kärntnertortheater in Vienna, Der Postzug oder die edlen Passionen (The post horses or the noble passions) soon delighted audiences in the many theatres that took it into their repertory, including that of the Esterházy princes.

The satirical tone of Der Postzug, with its focus on the conversation of a stereotyped cast of landed noblemen and women, held such exceptional appeal that, slightly less than a decade later, no less a personage than Frederick the Great declared it was the only ‘true comedy’ in German theatre,5 and indeed that its author appears to us today as having blazed the trail for Nestroy’s farces.6 To understand why this was so, it will be useful here briefly to summarise (in the words of the Ayrenhoff specialist Matthias Mansky) the plot of the play, whose title refers to the term used at the time for a team of four coach horses.

The engagement of the young Leonore to Count Reitbahn is to be celebrated at Forstheim Castle. While Baron von Forstheim pursues his passion for hunting, his wife is busy with the preparations. Everything is topsy-turvy in the house, especially because the visit is announced of Count von Blumenkranz, a friend of the groom, who since his return from Paris has ‘set the tone everywhere that gallantry is practised’. Meanwhile, the future bride, who in fact loves not Reitbahn but Major von Rheinberg, deplores her fate. But in the end nothing turns out as expected. While the Major manages to secure Forstheim’s favour with the gift of two greyhounds, Reitbahn is much taken with his (Rheinberg’s) post horses. Since the Major does not want to sell his pintos, however, they negotiate a barter deal: in return for the horses, Reitbahn renounces his marriage with Leonore. After Forstheim gladly consents to the union between his daughter and the Major, the deeply disappointed Baroness finally has to resign herself to the match.

But why should our Symphony in A major in particular, with its unusually high Hoboken number for the date of composition, have any particularly close connection with Ayrenhoff’s comedy? A perfectly justifiable question, which can be answered in two different ways – one invoking our limited knowledge of the genesis of Hob. I:65 and the theatrical programme presented at Eszterháza Palace at the same time; the other attempting an interpretation of superordinate narrative structures. Let us start with the latter approach.

Since one can expect incidental music for the stage to serve the theatrical production with which it is associated, the question arises of whether selected passages in the text can be used to show how Haydn’s music might comment on, interpret, supplement or even continue the content of the drama. So let us try the idea out in practice . . .

At the beginning of the second act of Ayrenhoff’s Der Postzug,the following conversation takes place between the chambermaid Lisette and the Forstheim family steward:7

LISETTE. [...] But tell me, Mr Steward or Interim Major Domo: how are things going at table?

STEWARD. Rather at sixes and sevens, my dear Lisette. Our young lady, it seems to me, did not really behave as the Baroness would have wished.

LISETTE. What do you mean?

STEWARD. She sits between the Major and her fiancé; and the Major is more likely to hear a hundred words from her than the fiancé to hear one.

LISETTE. Oh dear! And how does he react to that?

STEWARD. Fortunately, he didn’t always have time to worry about it, since the Captain, who was sitting on the other side of him, gave him an opportunity to talk about horses from time to time; and then he forgot about his future bride. But the Baroness sometimes made sour faces.

Here, then, we are told of a comic scene that has not been shown in the stage action and that has just taken place, i.e. ‘between the acts’. And it is precisely this situation that the music of the Andante of Hob. I:65 seeks to express in almost pantomimic fashion. It opens with a cantabile opening melody in the first violins (Fräulein Leonore?), interrupted by a military fanfare. The violin melody begins with an anacrusis, on a’’ – a note that Haydn initially repeats twenty-two times, and later even thirty-two times (Leonore explains her love in ‘one hundred words’ to her Major Rheinberg, whom the preceding interjection in dotted notes on oboes and horns is probably intended to evoke). It is no wonder that a low-pitched three-bar unison phrase in the string tutti (the ‘sour faces’ of the Baroness?) objects to this, while the horse-mad Count Reitbahn is unaware of all around him because he is too busy ‘talking shop’ with Captain Edelsee (conjunct double appoggiaturas in the first violins suggesting braying donkeys).

Seen in this light, a symphonic movement that hitherto appeared to resemble an ‘incoherent stringing together of quirkily shaped motifs’8 suddenly turns into a genuine entr’acte. But there is better to come, because now Lisette learns the result of the performance by the jobbing musicians ‘who played in His Lordship’s tavern at the last church consecration festival’, where they offered ‘the most beautiful minuets’ and ‘Styrian dances’:9

LISETTE. . . . the cooking was certainly not bad today.

STEWARD. Did you know that, on account of the stinking stable boys who had to wait at table, I fumigated the room before dinner?

LISETTE. You don’t say!

STEWARD. But Count Blumenkranz can’t stand incense. With a phial of eau de lavande under his nose, he assured the company that he had never have been more convinced of the strength of his nature than he is today, because he didn’t faint at the disgusting smell.

LISETTE. Oh heavens! And did the Baroness not faint herself when he said that?

STEWARD. I don’t know if she rightly understood him. She was busy giving the order for the musicians to start playing. And – you’ll die laughing! – she had to stop the music halfway through the first minuet.

LISETTE. That’s why I didn’t hear it.

STEWARD. Count Blumenkranz begged her, for the life of him, at least to spare his ears, as his nose would be tainted for weeks to come.10

A Menuetto that mutates into a ‘Steyrischer’ (Styrian folk dance) through gradual shifts in the placing of the strong beats, which are marked by trills and forte accents, only to go astray in the ensuing Trio section in an alternation of ornamented ostinato and hemiolic rising sequences11 – the tragicomedy of the situation just described could scarcely have been translated into music more vividly.

Now that we have seen how the middle movements of Symphony no.65 could ‘demonstrably’ constitute a two-part (or two-movement) suite of ‘entr’acte music’, the question remains as to how the opening Vivace con spirito and the concluding Presto could be related to Der Postzug and its not-so-noble passions. Viewed from the perspective of both form and character, they certainly fulfil their respective functions – namely those of overture and finale music – to the best of their ability. Thus the beginning of the first movement, with its tutti chords intended to kill off audience noise, its contrast between ‘delicate violin melody’ and ‘impassioned unison rhythms in the low strings’12 – one recalls the motivic diversity of the Andante discussed above – immediately explores one of the essential conflicts of the stage action to come: a noble young lady from the country who opposes her social climbing mother’s marriage plans for her.

The last word in Der Postzug goes to Baron Forstheim, the happy recipient of a pair of Hungarian greyhounds presented by his future son-in-law:

Ah, my dear, it has all turned out well. The wedding is tomorrow. Tell little Leonore today what she has to expect from that. Invite all the neighbours to come, everyone except that stupid Lembrand! He shall never eat a bite of my venison in his life! - And you, Major, come with me to the [hunting] stand.

And what does a Haydn have to add to that on the musical level? A finale in 12/8 time which is nourished by the (mainly rhythmic) preoccupation of the horn and various other sections of the orchestra with a French hunting signal called ‘Ton pour la quête’! Why was that signal sounded at the time? To unleash the dogs that are to flush the stag from its lair!13

Since the comedy by our talented Vienna-born dramatist, recently promoted to major, first trod a candlelit stage in 1769 – the same year to which Haydn scholars date Hob. I:6514 – we should conclude this article by taking a look at conditions in the Eszterháza theatre at that time.

The first troupe that Prince Nicolaus engaged or intended to engage in Eszterháza was that of Simon Friedrich Koberwein, the son of a Viennese wine merchant, who had started his theatrical career in 1753 in Linz (under Anton Jakob Brenner), went into association with his brother-in-law Johann Joseph Felix von Kurz (known as Bernardon) in the early 1760s, and took over Franz Gerwald Wallerotti’s company in Munich in 1763. Around 1766 he entered a partnership with a certain Franz Joseph Hellmann, alongside whom he had already acted in Brno, Pressburg and for some months at the ‘hochfürstlich esterházyches Theater’ by the time the two men signed a three-year contract with the last-named on 31 July 1769, due to come into effect on 1 May 1770. The agreement stipulated, among other things, that the ensemble was to ‘perform a play every day . . . with at least fourteen appropriate and experienced persons, and to acquire the necessary costumes and the plays themselves’; but it was dissolved after only a few months, in October 1769, when the two managers received a request to return the contract and the performing licence to the princely chancellery. This is probably explained by an intrigue on the part of Catharina Rößl. Shortly before this time, ‘die Rößlin’ had left the Hellmann-Koberwein company to join her husband in Franz Passer’s troupe – a rather piquant business, considering that she was rumoured to have had an affair with Kleinrath, the head of the Esterházy Chancellery. Be that as it may, the success of Hellmann and Koberwein’s earlier performances, and their letters of protest, were all in vain: in the spring of 1770 Passer took over the theatre business at Eszterháza Palace.

While there has recently been growing evidence that a hitherto unknown court festival was celebrated at Eszterháza around mid-October 1769, which, in addition to a performance of Giacomo Rust’s opera La contadina in corte, might have featured Der Postzug along with masked balls and fireworks, the search for corresponding musical sources has unfortunately yielded no results so far.

A monogram artfully intertwining the letters ‘FD’, which adorns the title page of a copy of Hob I:65 by an anonymous Austrian scribe that was once purchased by the celebrated Polish princess, patron of the arts and active theatre-goer Elżbieta Izabela Lubomirska for her music library at Łańcut Castle15 might indicate that the score in question was once in the possession of the actor Franz Diwald(t). He was a member of the Passer company and was later to work as an impresario with his own troupe of actors at Eszterháza between 1778 and 1785.

1 H. C. Robbins Landon, ‘Haydn: Symphonies nos. 50, 64 & 65’, booklet note to recording by Tafelmusik conducted by Bruno Weil, Vivarte / Sony Classical 1994, p.8.

2 ‘Die Tagebücher des Karl Grafen Zinzendorf (1764–1790)’, Umgang mit Quellen heute: Zur Problematik neuzeitlicher Quelleneditionen vom 16. Jahrhundert bis zur Gegenwart, ed. Grete Klingenstein, Fritz Fellner and Hans Peter Hye (Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2003. Teil II Editionsprojekte), pp.263-266, here p.264.

3 Zinzendorf wrote his diary in (slightly approximate) French. (Translator’s note)

4 His career is extensively covered in Matthias Mansky, Cornelius von Ayrenhoff. Ein Wiener Theaterdichter (Hanover: Wehrhahn Verlag, 2013).

5 ‘I will not speak to you of German theatre. Melpomene has been courted only by surly lovers, some walking stiffly on stilts, others wallowing in the mud, and all of whom, refusing her laws, knowing neither how to interest nor how to move her, have been expelled from her altars. Thalia’s lovers have been more fortunate; they have at least furnished one true comedy; I speak of the Postzug. It is our morals, our absurdities that the poet depicts on stage; the play is well done. Had Molière worked on the same subject, he would not have done better’: Frederick II of Prussia, De la littérature allemande, des défauts qu'on peut lui reprocher, quelles en sont les causes, et par quels moyens on peut les corriger (1780) [here newly translated from Frederick’s original French text, available at http://friedrich.uni-trier.de/fr/oeuvres/7/id/004000000/text/ - Translator’s note].

6 See Matthias Mansky, ‘“Hätte Molière den gleichen Stoff behandelt, es wäre ihm nicht besser gelungen” (Friedrich II.) – Cornelius von Ayrenhoffs Komödien zwischen Lustspiel- und Possendramaturgie’, Nestroyana, 27 (2007), Heft 1–2, pp.8–19, especially 14-16 and 19.

7 [Cornelius von Ayrenhoff,] Der Postzug oder die noblen Passionen. Ein Lustspiel in zween Aufzügen. Aufgeführt auf dem k. k. privilegirten Theater. Zu finden beym Logenmeister (Vienna: Joseph Kurtzböcken. N. Oe. Landschafts und Universitätsbuchdruckern, 1769), Act Two, Scene 1, pp.50-51.

8 Christian Moritz-Bauer, ‘Gli Impresari’, programme note for the Haydn Night of the Basel Chamber Orchestra in the Haydn2032 series, Sunday 1 October 2017, 7 p.m., Martinskirche Basel, p.13.

9 Der Postzug oder die noblen Passionen, 1769, p.12.

10 Ibid., pp.51-52

11 See James Webster, ‘Entertainment Symphonies, c.1765-1768’, booklet note to the three-CD set ‘Haydn Symphonies, volume 5’ (London: Decca-L’Oiseau-Lyre, 433 012-2, 1992), pp.25-26.

12 Walter Lessing, Die Sinfonien von Joseph Haydn, dazu: sämtliche Messen, vol. II (Baden-Baden: Südwestfunk, 1988), p.77.

13 Jean de Serre de Rieux, Les Dons des enfans de Latone: La musique et la chasse du Cerf. Poëmes dédiés au Roy (Paris: 1734), p.333 (and 289).

14 Joseph Haydn: Sinfonien um 1766-1769 [Hob. I:26 (Lamentazione), 38, 41, 48 (Maria Theresia), 58, 59, 65], ed. Andreas Friesenhagen and Christin Heitmann (Munich: G. Henle Verlag, 2008 (= Joseph Haydn Werke, Joseph Haydn-Institut, Köln, Reihe I, Bd. 5a), pp.XI-XII.

15 Ibid., p.195.

to the shop

Line-up

Basel Chamber Orchestra

Giovanni Antonini, conductor

- Line-up orchestra

1st violin Yuki Kasai, Valentina Giusti, Elisabeth Kohler-Gomes, Eva Miribung, Tamás Vásárhelyi Irmgard Zavelberg

2nd violin Barbara Bolliger, Anna Faber, Regula Keller, Regula Schaer, Mirjam Steymans-Brenner

Viola Mariana Doughty, Bodo Friedrich, Anna Pfister, Katya Polin

Cello Christoph Dangel, Georg Dettweiler, Hristo Kouzmanov

Bass Stefan Preyer, Daniel Szomor

Flute Isabelle Schnöller, Emiliano Rodolfi

Oboe Emiliano Rodolfi, Thomas Meraner

Bassoon Carles Cristobal Ferran, Letizia Viola

Horn Konstantin Timokhine, Mark Gebhart

Trumpet Christian Bruder, Jan Wollmann

Timpani Alexander Wäber

Concerts

Basel

Sunday, 01.10.2017

Martinskirche Basel

Vienna

Saturday, 07.10.2017

Musikverein Vienna

Rome

Sunday, 08.10.2017

Santa Cecilia, Rome

Biographies

Orchestra

Basel Chamber Orchestra

Orchestra

The Basel Chamber Orchestra is deeply rooted in the city of Basel - with its two subscription series in the Stadtcasino Basel as well as its own rehearsal and performance venue, Don Bosco Basel. With world tours and more than 60 concerts per season, the Basel Chamber Orchestra is a popular guest at international festivals and in Europe’s most important concert halls.

As the first orchestra to be awarded the Swiss Music Prize in 2019, the Basel Chamber Orchestra stands out for its excellence and diversity as well as for its depth and consistency. Its interpretations are deeply immersed into the relevant thematic and compositional worlds: in the past with the "Basel Beethoven" or with Heinz Holliger and our "Schubert Cycle". Or as with the long-term project Haydn2032, the study and performance of all Joseph Haydn's symphonies up to the year 2032 under the direction of principal guest conductor Giovanni Antonini and together with the Ensemble Il Giardino Armonico. From the current season onwards, the Basel Chamber Orchestra has decided to devote itself to all the symphonies of Felix Mendelssohn under the direction of the early music specialist Philippe Herreweghe.

The Basel Chamber Orchestra frequently collaborates with selected soloists such as Maria João Pires, Jan Lisiecki, Isabelle Faust and Christian Gerhaher. The Basel Chamber Orchestra presents its broad repertoire under the artistic direction of the first violins and the baton of selected conductors such as Heinz Holliger, René Jacobs and Pierre Bleuse.

The concert programmes are as diverse as the 47 musicians and range from early music on historical instruments to contemporary music and historically informed interpretations.

An important element of the work is the future-oriented education programs in large-scale participatory projects involving creative exchange with children and young people.

The creative work of the Basel Chamber Orchestra is documented by an extensive and award-winning discography.

The Clariant Foundation has been the presenting sponsor of the Basel Chamber Orchestra since 2019.

Conductor

Giovanni Antonini

Conductor

Born in Milan, Giovanni studied at the Civica Scuola di Musica and at the Centre de Musique Ancienne in Geneva. He is a founder member of the Baroque ensemble “Il Giardino Armonico”, which he has led since 1989. With this ensemble, he has appeared as conductor and soloist on the recorder and Baroque transverse flute in Europe, United States, Canada, South America, Australia, Japan and Malaysia. He is Artistic Director of Wratislavia Cantans Festival in Poland and Principal Guest Conductor of Mozarteum Orchester and Kammerorchester Basel.

He has performed with many prestigious artists including Cecilia Bartoli, Kristian Bezuidenhout, Giuliano Carmignola, Isabelle Faust, Sol Gabetta, Sumi Jo, Viktoria Mullova, Katia and Marielle Labèque, Emmanuel Pahud and Giovanni Sollima. Renowned for his refined and innovative interpretation of the classical and baroque repertoire, Antonini is also a regular guest with Berliner Philharmoniker, Concertgebouworkest, Tonhalle Orchester, Mozarteum Orchester, Leipzig Gewandhausorchester, London Symphony Orchestra and Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

His opera productions have included Handel’s Giulio Cesare and Bellini’s Norma with Cecilia Bartoli at Salzburg Festival. In 2018 he conducted Orlando at Theater an der Wien and returned to Opernhaus Zurich for Idomeneo. In the 21/22 season he will guest conduct the Konzerthaus Orchester Berlin, Stavanger Symphony, Anima Eterna Bruges and the Symphonieorchester de Bayerischer Rundfunks. He will also direct Cavalieri’s opera Rappresentatione di Anima, et di Corpo for Theatre an der Wien and a ballet production of Haydn’s Die Jahreszeiten for Wiener Staatsballett with the Wiener Philharmoniker.

With Il Giardino Armonico, Giovanni has recorded numerous CDs of instrumental works by Vivaldi, J.S. Bach (Brandenburg Concertos), Biber and Locke for Teldec. With Naïve he recorded Vivaldi’s opera Ottone in Villa, and, with Il Giardino Armonico for Decca, has recorded Alleluia with Julia Lezhneva and La morte della Ragione, collections of sixteenth and seventeenth century instrumental music. With Kammerorchester Basel he has recorded the complete Beethoven Symphonies for Sony Classical and a disc of flute concertos with Emmanuel Pahud entitled Revolution for Warner Classics. In 2013 he conducted a recording of Bellini’s Norma for Decca in collaboration with Orchestra La Scintilla.

Antonini is artistic director of the Haydn 2032 project, created to realise a vision to record and perform with Il Giardino Armonico and Kammerorchester Basel, the complete symphonies of Joseph Haydn by the 300th anniversary of the composer’s birth. The first 12 volumes have been released on the Alpha Classics label with two further volumes planned for release every year.

Videos

Recordings

VOL. 7 _GLI IMPRESARI

CD

Giovanni Antonini, Basel Chamber Orchestra

Symphonies No.9, No.67, No.65

W. A. Mozart: Thamos. King of Egypt

Available at:

Bider&Tanner, Basel

Outhere Music

Download / Stream

VOL. 7 _GLI IMPRESARI

Vinyl-LP with book (download code CD included)

Giovanni Antonini, Basel Chamber Orchestra

Symphonies No.9, No.67, No.65

W. A. Mozart: Thamos. King of Egypt

Essay "His Prince and He" by Daniel Kehlmann

Available at:

Bider&Tanner, Basel

Outhere Music

Peter van Agtmael / Magnum Photos

Biography

Photographer, Magnum Photos

Peter van Agtmael

Photographer, Magnum Photos

Peter van Agtmael was born in Washington DC in 1981. He studied history at Yale.

His work largely concentrates on America, looking at issues of conflict, identity, power, race and class. He has worked extensively in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Israel/Palestine.

He has won the W. Eugene Smith Grant, the ICP Infinity Award for Young Photographer, the Lumix Freelens Award, the Aaron Siskind Grant, a Magnum Foundation Grant as well as multiple awards from World Press Photo, American Photography Annual, POYi, The Pulitzer Center, The Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University, FOAM and Photo District News.

His book, 'Disco Night Sept 11,' on America at war in the post-9/11 era was released in 2014. Disco Night Sept 11 was shortlisted for the Aperture/Paris Photo Book Award and was named a ‘Book of the Year’ by The New York Times Magazine, Time Magazine, Mother Jones, Vogue, American Photo and Photo Eye.

"Buzzing at the Sill," a book about America in the shadows of the wars, was released in the Spring of 2017. Upon pre-release, it was named one of Time’s “Photo Books of the Year” for 2016.

He is a founder and partner of Red Hook Editions, a publishing company based in Brooklyn. He is a mentor in the Arab Documentary Photography Program in Beirut.

Peter joined Magnum Photos in 2008 and became a member in 2013.

Father always had to be surrounded by music. They talked him into it, all those aesthetes and scribblers. A balmy summer evening: music. A midday banquet: music. A party: a vast amount of music. A public holiday: religious music. Someone receives a medal: music. Important guest visits: more music than ever. Not so important guest visits: music anyway. In church, there is already music, and outside in the garden, where what one actually wants is a little peace and quiet, so that one may listen to the wind in the trees and the chirruping birds and the babbling brook, there we have garden music.

And he created all of this music.

How can one individual invent so much strumming and singing? Something is not right with a person like that! He writes it, he plays it, he beats time, he beats the keys, he fiddles, he blows the horn. He has been here for twenty-eight years, and he can do it all! The only thing he cannot do is peace and quiet.

Excerpt from the essay "His Prince and He" by Daniel Kehlmann

The essay "His Prince and He" by Daniel Kehlmann was published in the vinyl edition vol. 7.

Biography

Writer

Daniel Kehlmann

Writer

Daniel Kehlmann was born in Munich in 1975. His works have won the Candide prize, the WELT prize, the Kleist prize and the Thomas Mann prize. His novel „Measuring the world“ is considered one of the greatest successes in postwar German literature. He is currently teaching at New York University.